How the other two-thirds live and work

- Published

No-one in Delhi is protected from the polluted air

An early morning drive through the city helps to give new perspectives. So I've been told. I'm not that good with mornings.

So a few hours before fresh figures were released this week on the state of the jobs market, I found myself heading for the station in Delhi, on a journey that brought wider reflections on how people make a living.

Stray dogs had scavenged what they could through the night, and lay curled up. A few bleary people were stirring, one or two firing up a gasoline stove, for tea.

Hundreds upon hundreds of bundles of blanket, each containing a slight human frame, lay along the raised pavements, sheltered from rain but with little protection against the foggy winter chill.

No-one in the city - even the richest - is protected from the polluted air, tinted orange in daylight, catching the throat, tiring the eyes, tasting on each breath.

My destination was Delhi's main railway station. The hustlers will still be asleep, but the porters were up and eager for custom. The concourse was filled with the bright colours of clothing and bedding where hundreds of families were ending their night's rest as I arrived, having bedded down there ahead of early departing trains.

National pride

The newspapers led with news from Davos.

Indian prime minister Narendra Modi on Tuesday delivered a long speech to business leaders at the super-rich, super-powerful Alpine summit, emphasising India's heritage and culture, telling them that globalisation is shrinking and at risk, "its shine is fading", but that India is open for business and aims to be a "job-giver" more than a "job-taker".

On Friday, the nation marks Republic Day with a grand parade through New Delhi's broad avenues. With Swiss snow barely melted from his boots, Mr Modi will host a clutch of other Asian leaders from countries to his south-east, attending an ASEAN summit.

He's using this display of national pride and military pageant (I passed the camel cavalry of the Border Force, post-rehearsal, bedraggled by rain) to tell them that India is a superpower.

It is regional, perhaps, for now, but becoming a global force in time, if not already. So, for your kind attention, ASEAN, China is not the only game on the continent.

Tight market

Two questions you may be asking. What am I doing in India, when there are export figures to be reported in Scotland? And what about those job figures?

The first answer I'll leave to another day. The second one, on jobs - well, there may be some value in putting Scotland's employment picture into an international perspective.

Yes, it remains in line with the UK headline figures, which remain unusually strong. Employment levels have rarely been higher, and rate well by international standards.

Unemployment figures have been at, or around, a historic low, and that too compares well with the neighbours.

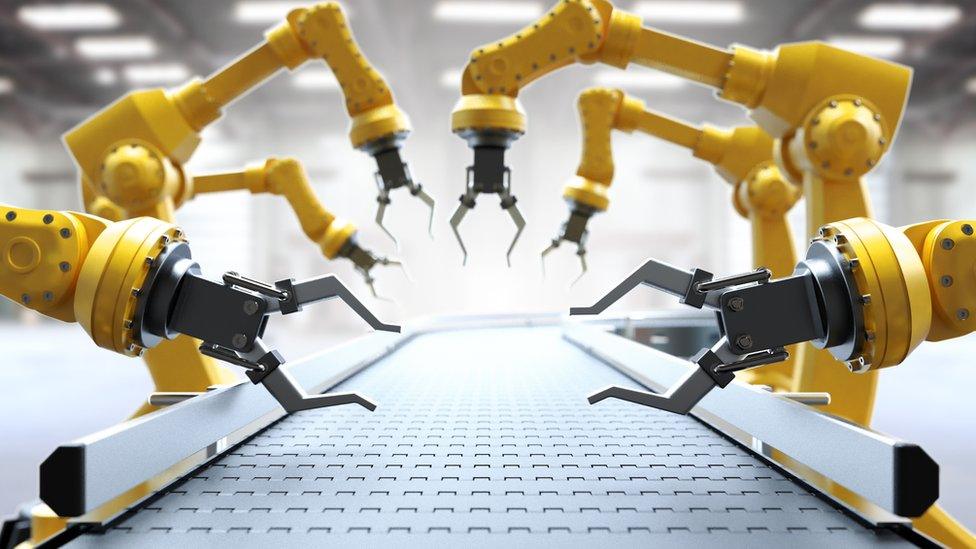

The rise of the robot is seen by many as a big threat to the less skilled worker

The underlying factors that make fewer headlines are around the vulnerability of those jobs, and the squeeze on real pay as price inflation continues to outstrip wage rises.

Even with a tight labour market, and much concern about skill shortages, employers are able to hold down pay increases.

Instead, it is expected that they may choose to increase hours, paying more in overtime rather than recruiting and training more workers. In some cases, they may require longer hours without paying more.

I've seen that happen to former colleagues in the newspaper industry, for instance - lucky, arguably, to retain a job, but under immense pressure to keep delivering news in print and online with fewer staff.

Bosses have the option of offering skill upgrading, to help workers become more productive, and to help retain them. Losing staff, and having to recruit, is expensive.

Or bosses may run the sums on how much it would cost to invest in new equipment rather than looking to the labour market to hit growth targets.

With rapid advances in technology, the rise of the robot is seen by many as a big threat to the less skilled worker, and many more skilled ones too.

Extreme poverty pay

All these factors help fuel a sense of insecurity, which has been driving political responses across Europe and the USA.

But the international picture tells us that insecurities close to home are as nothing compared to the lot of many working people elsewhere. And that, in turn, helps explain why so many of them are willing to take immense risks to migrate into more prosperous job markets.

This week, the International Labour Organisation published its take on the two years ahead. It contained good news, but also not such good news.

It showed how much the numbers on extreme poverty pay have fallen, and sharply, over the past two decades.

In South Asia - India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and smaller neighbours - that is around 300 million fewer people in working poverty since 2004. But the number is still big - 285 million this year, or 41% of workers.

It's the kind of change that doesn't make many headlines, but is of massive significance for the economy, for social improvement and for humanity, as emerging economies emerge.

Apart from easing deprivation, it has helped build a ready market, with at least some disposable income, on which new businesses are thriving.

The reckoning behind the report was also that the uplift in demand across the world economy should help reduce unemployment in 2018 and 2019, including in some dark spots such as southern Europe.

Breathtaking pace

Not such good news: the reduction in poverty pay is slowing. Extreme poverty pay is counted as less than $1.90 per hour, adjusted for the amount it can purchase in-country.

In sub-Saharan Africa, according to the ILO, that accounted for 37% of workers in 2017.

"Moderate working poverty" means pay between $1.90 and $3.10, adjusted for purchasing power in each country. In sub-Saharan Africa, that accounted for a further 24% of workers last year.

China's one-child policy has resulted in a shrinking Working-age population

Translate the percentages into actual Africans, and you find it means 228 million people. It includes 38 million young Africans, or two-thirds of those entering the labour market.

In India, that is the kind of money earned by the rickshaw-wallahs and street cleaners who sleep rough in Delhi and every other city on the Indian plains. Many come to the big city because there's no income to be had in their villages.

And unlike China, where the one-child policy now means a shrinking working-age population, on the sub-continent, the working population is rising at a breathtaking pace, of nearly 7% last year, and more than that this year.

Even if India's healthy growth rate can keep generating new jobs in abundance, it won't reduce unemployment by much.

Vulnerable workers

Another piece of less welcome news from the ILO is that the reduction in the number of worldwide workers classified as being vulnerable (working on their own account or informally in a family business, such as a farm) is not just slowing but may be about to go into reverse.

We know what "vulnerable" can often mean in Britain - the gig economy, zero hours contracts, self-employed "consultants" who struggle, often in advancing years, to get back into a full-time post.

In India, it's all that but without the minimum wage or the safety net of a welfare state, including pensions - however inadequate that might seem in Britain.

The sectors most likely to have vulnerable workers, as well as the low paid, are the ones that remain dominant, notably agriculture. Whereas the number of farm workers in China and its neighbours has plummeted, they remain close to 60% in South Asia.

So "vulnerable" workers on the Indian sub-continent account for 72% of the workforce. For women, that is around 81%.

We've long known that India's work, working conditions and pay were very different from Europe's. But in a global economy, the connections across continents matter more.

And with the ILO watching closely for social unrest linked to labour market weakness, it's a reminder that the consequences can reach across continents too.

Older and inflexible

Two other points worth noting from the ILO report.

One is about older workers. The UK has just passed the threshold of one million people working past their 65th birthday by last autumn.

In Scotland, there's been a sharp rise in the past year, to 99,500, or 9.9% of that age group.

Why? Partly because they can. The law changed. But also because many feel they have to. Occupational pensions aren't what they were. The kids may be grown up, but they often still need support.

Some believe older workers are a hindrance on productivity gains

That change in a productive later life can be seen as a good thing. But the blunt-speaking labour market economists of the ILO are not that flattering about the impact on the economy of this ageing workforce being a factor around the world.

Older workers bring the benefits of experience and consistency. But they are also reckoned (it says here) to be a hindrance on productivity gains.

Why so? They are either slow to learn new tricks with technology, or employers are unwilling to pay for upskilling them. They are reluctant to take a risk on leaving work, because it's harder to get another job when you're older.

So inflexible older workers are seen as slowing up the process of adjustment within the economy, both to new ways of working and to new industries.

Caring for 'seniors'

Whether oldies are to blame, or employers, or governments, that's not so good for the economy. And if left to the market, it means a skills gap that governments will have to fill.

When these workers get older and cannot work any longer, that's when the other labour market factor kicks in.

Caring for elderly people is clearly a big growth area.

President Trump may not highlight it when he talks about Making America Great Again, but the biggest employment prospect for Americans in the next six years is in caring for "seniors". Some 633,000 new care jobs are expected to be created in that time.

And so it goes around the world. Either caring has to be made into a more attractive, higher status, better paid option, says the ILO, or we'll see even more people - mainly women - opting out of paid work to look after ageing relatives.

It may look and feel like very hard real work to those doing it. But it could often be better delivered by those with training. And in an economy measured by statisticians, unpaid work doesn't count.