Espresso economy: making it slowly

- Published

If you like your coffee, you've probably stood in the queue behind someone wanting a decaff soya machiatto latte with triple salchow twist, wishing they'd order something a bit simpler, and faster to make.

But the making of coffee can be something of a performance, particularly if the freshness of the grind and the frothiness of the milk is what you're paying more than three quid for.

Only so many people can squeeze behind the counter to make them. So those of us who like a hit of fancy caffeine have to show a bit of patience.

In more economic terms, we have to accept the limits on the efficiency and speed of production. That freshness and personal service puts a constraint on the barista's productivity.

In other words, it's hard to see how the barista's employer can get her, or him, to deliver more coffees per hour. At best, the coffee chain can persuade the customer to add value by paying more for extra elements to the coffee that take little time to add.

Quality measure

It's easier to see how someone on a production line can improve productivity. Processes can be honed. A culture of continuous improvement can look for the edge that gets the job done with less resource, or with more reliability, reducing the cost of wastage.

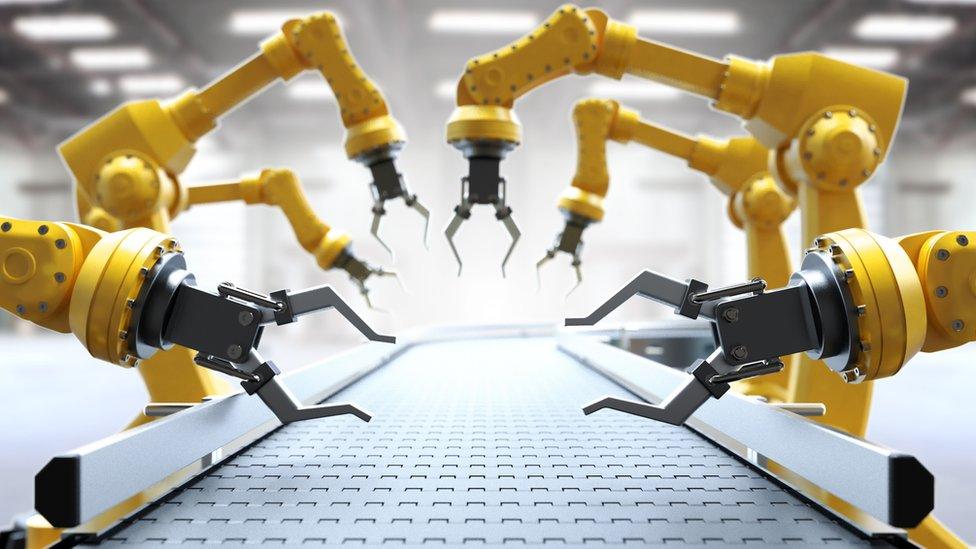

Or bosses may sanction the capital expenditure with which to buy new equipment, some of which may replace workers.

Automation offers one route to increased productivity

But for those providing a service, getting more value out of each hour worked is harder. It's true of making coffee, and of serving in a restaurant or hotel. It's a challenge in education or the health service, particularly if the measure is of quality as well as patient or pupil throughput.

This matters because, without improving the value a worker adds per hour, wages and prosperity are going to stall. And that's one of the key economic problems - arguably the biggest one - that we currently face.

Productivity growth has stalled in Britain. And we have new evidence of how the stalling is more of a problem in Scotland.

There was a sort of rejoicing some months back, or at least relief, when the figures for 2015 (they take a while to collect) appeared to show that Scottish productivity had caught up with that of the UK as a whole.

That is, the amount of output per hour worked in Scotland was getting very close to the amount for the UK. That's after years when Scots had, on average, been less productive. In the modern era, using modern data, Scotland has lagged. But, we told ourselves last year, not any longer.

It was pointed out that to have caught up with the UK on productivity was only the start. The UK has a lot of catching up to do with its competitors.

Volatility

But new Scottish government figures, published on Wednesday, suggest that 2015 may have been something of a peak, from which Scottish productivity has since been on the slide.

Every way you look at it, it's down. The last positive quarter was in July to September 2015.

Up to the third quarter of last year, the previous five quarters had been negative. Just taking the previous four quarters adds up to an annualised decline of 3.2%.

But get some clever statisticians to iron out the volatility and seasonal factors (if you insist, "a trend-based estimate of quarterly growth based on a centred moving average") and you get to a mere 0.7%. Still negative, though.

If you average things over the year, which is another way of ironing out volatility, output per hour was down more than 1% in 2016. We don't have the full figures for 2017, but it looks like ending up as a steeper drop.

And for those who see comparison with the UK as being the key measure of success, how is it looking? Well, it's looking a bit like divergence, and not in a good way.

The gap closed at its fastest rate in 2008 and 2009. We could guess that's because the high productivity of London's financial sector took a very big dive with the great recession, making Scots look relatively better.

Since 2009, Scottish productivity has been above 96% of the UK's level, and the gap was closing. But in the past two years, it's widened slightly.

Is there a particular sector of the economy that helps explain this? Oil and gas or finance, for instance? The statisticians have done some experimental work on this. It tends towards showing only why further statistical delving is of limited use.

Construction figures can be helped a lot by capital investment, for instance. And if the measure of the property sector is value added, then rising house prices can make productivity look good, without anything productive having happened.

The less unreliable numbers show how weak productivity growth is in hospitality, and in government services.

Worryingly wide

And indeed, all of these are merely numbers, derived from survey evidence of the hours people work and separate surveys of employers about how much they produce. They reflect, to a significant extent, the successful jobs market in which unemployment is very low. (You could make productivity look much better by firing the least productive workers, though to be clear, that's not a recommendation from me.)

The statistics can reflect labour force changes in the way people work, and the patterns in which employers offer additional hours. So you could choose to pick holes in the methodology. (One proposal from an independence-minded think tank this week is that Scotland's statistical problems can best be addressed with its own statistical agency.)

You could also argue that the gap with the rest of the UK is not that worryingly wide.

But the trend is of very weak improvement. And in recent quarters, it's been going in the wrong direction. The challenge remains of identifying why productivity has been so poor, and what can be done about it.

Fundamentals

So I offer, in full, the Scottish government's take on the numbers: "Scotland's economy continues to grow and, while there is no room for complacency, it is encouraging that these statistics show a strong increase in the number of hours worked in recent quarters.

"Despite the dip in productivity over the last year, annual productivity levels have increased by 5.4% in Scotland since 2007, compared to only 1.4% growth for the UK as a whole.

"The most recent labour market statistics show our unemployment rate has been lower than the UK's for 11 consecutive months and we are also outperforming the UK on employment, unemployment and inactivity rates for young people and women, demonstrating that the fundamentals of our economy continue to be strong.

"However it cannot be stressed enough that Brexit remains the single biggest threat to our economy. Our latest analysis, confirmed by the UK government's own analysis shows a hard-Brexit could cost Scotland's economy £12.7 billion a year by 2030, so we continue to use all of the powers at our disposal to grow our economy."

So the analysis there is: more people are working, and longer hours. The chosen benchmark for these numbers is by comparison with the UK as a whole. Taking 2007 as the starting point that proves the point most clearly, the productivity gap with the UK has narrowed (but both are very weak).

And, according to this Holyrood view, Brexit is the big threat. Well, maybes aye... But even if the process stopped now, it's not clear that would do anything to solve the productivity puzzle. And that puzzle, with respect, is "a fundamental of our economy".