Whose economy is it anyway?

- Published

Who owns the economy? Daft question? OK, who controls it? That ought to be easier.

You could say it's big corporates, a corporate elite, the Treasury, the Cabinet, evil bankers or central bankers. You could, if you insist, say it's a vast global conspiracy.

What you're unlikely to respond is that it is controlled by myriad decisions made by billions of workers, consumers, savers and investors. Even if that is true, it's not the perception.

And for the people with control of the levers of power, that has suited them just fine. Economics is not just dismal but complicated, and it's been easy to conclude that it is not to be trusted with those outside the fiscal, monetary and corporate priesthood.

But those same people have noticed the change afoot. How could they miss it? Populism has set electoral politics alight with indignation that prosperity and globalisation may not be working for everyone, or even the majority.

Findings of an opinion survey, commissioned by the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) found 72% of people think they have little or no influence over big economic decisions. (I'm surprised it wasn't more.)

Current accountability

Among the more thoughtful responses has been the central bankers. They know they wield a lot of power over abstract notions around interest rates, bank lending and money supply. They also know that they lack accountability. That makes them unusually considered about how they wield their power and communicate with the people affected.

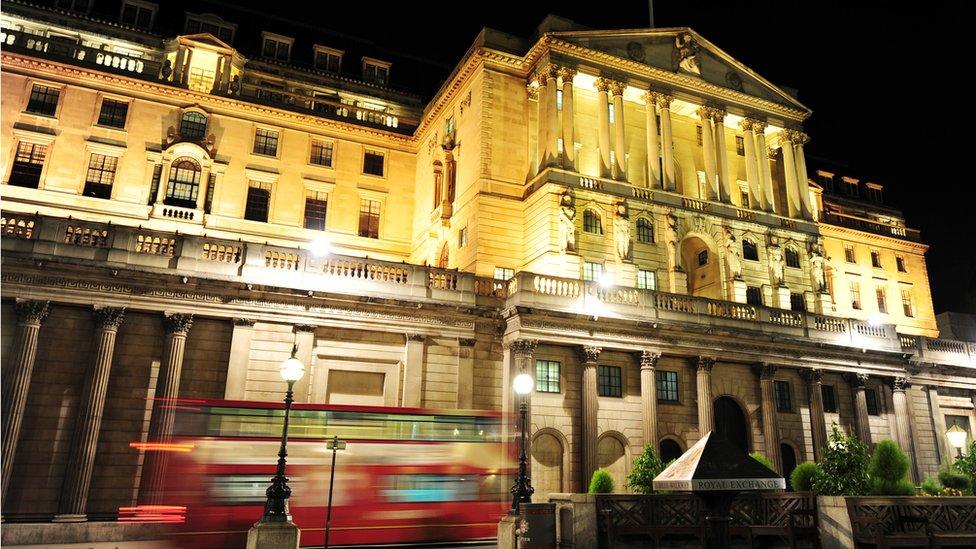

Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, was talking about it in a speech on Tuesday, noting that for the first 300 years of the Old Lady's existence, it didn't bother to communicate much. In the past 25 years, that has changed, a lot.

Andy Haldane admits the Bank is not always understood

"Seventy years ago, the Bank published precisely one speech a year," he said. "Today, rarely a day passes without multiple publications. Then, the Bank uttered publicly fewer than 5000 words per year. Last year, it uttered in excess of 4.5 million."

But do you understand those words? Mr Haldane tried a very rough estimate that 95% of the Bank's public output is not understood by 95% of people.

So before the public decide the central bankers are part of the swamp-dwelling elite whom Donald Trump was elected to drain out of Washington, the Bank of England is trying to get ahead of this shift it identifies as a going from broad trust in institutions to a conditional, personalised trust.

'Your bloody GDP'

Part of the distance from the powerful elite is in class, education, gender and experience. Some of it is distance itself. Andy Haldane had some telling insights into the view from the City of London, which may not surprise those of us out here in the provinces/sticks/boondocks.

What may be surprising is that one of Britain's smartest economists hadn't clocked this before.

"When UK GDP returned to its pre-crisis peak in 2014, economists told the world the economy had 'recovered'," he recalled.

"Around 30 seconds into a talk about the 'recovery' with charities in Nottingham in 2016, I was put straight. The language of recovery resonated with no-one in the room.

"This experience was repeated on TV, some months later during the referendum debate, when a questioner in Newcastle put straight one of the participants on the panel with the memorable line 'That's your bloody GDP, not ours'.

Newcastle is a long way from London

"When I returned to my desk from Nottingham and plotted GDP regionally as well as nationally, something surprising emerged from the numbers. In fact, GDP had passed its pre-crisis peak in only two regions of the UK - London and the South-East. No other region in the UK had in fact experienced a 'recovery', whether Nottinghamshire or anywhere else.

"My 'recovery' narrative, while true at the national level, had rightly fallen on sceptical ears at a regional level. Although the Bank's policies only operate at a national level, this is important context for how we and others communicate about the economy."

In post-industrial Wales, he remembered, Andy Haldane had found the claim of UK inflation at 2% looked very different from the personal inflation rates in the Valleys. Heating, transport, housing and food, for instance, took them to 10%.

High rates

It's not that long since this was a much more significant political issue, at least in Scotland. Nine years of exceptionally low interest rates have made the Bank of England much less unpopular than it was when interest rates were high.

Alex Salmond, as an opposition leader, railed against the bank for setting high borrowing rates to suit the overheated south-east of England. He wanted Scottish representation on the Bank's governing councils.

Once installed as First Minister and fighting the independence referendum, Mr Salmond would go on to argue for shared controls over the Bank of England between Westminster and an independent Scotland.

On the way to the forum

So there is a significant conclusion to Mr Haldane's observations. The Bank's chief economist was speaking at the Royal Society of Arts, on the same day it had published a report on 'Building a Public Culture of Economics'. That survey, finding 72% thought they had little or no control over economic decisions, also found 47% would trust them more if they felt 'people like us' had been involved.

That's why the RSA is pushing the idea of citizens' forums. It recommended one for each of the nations and regions of the UK, to interact with the Bank of England - both to hear the issues explained, and to give feedback.

Citizens' forums could be set up to gauge opinion

And with unnerving speed, Andy Haldane announced on the day of publication that the Bank intends to do just that, this year. There will be a forum for each of the agent's offices, which have been run by the Bank of England for 90 years.

These are the eyes and ears of the Bank, feeding back opinion from businesses, charities, voluntary organisations and councils. That's one citizens' forum for each English region, and one each for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

How will they be selected? That could be tricky where there is already a parliament or assembly, with members who feel it's their job to feed opinion into the Bank of England. Where there is no such representation, it could be an interesting building block to creating more of a regional identity and voice.

Tax and spend

A much bigger building block would be if the RSA's next recommendation were taken on - to set up citizens' forums for each nation and region to communicate with HM Treasury.

That would hear about the pressures on Chancellors both to cut taxes and increase spending, about the trade-offs and unintended consequences that flow from budget choices.

Each forum would also have the role of telling the Chancellor how they think those choices should be made.

I wouldn't hold my breath for that. From the Treasury's point of view, it spells trouble. 'Taking Back Control' is proving difficult enough with Brexit, without also creating new structures with which to further devolve powers.

MPs can claim to be the national sounding board, even if the people represent have other ideas.

So the RSA report has a third big recommendation: the next stages of devolution of power should also be deliberated by Citizen Joanne and Joe Public.