By yon bonnie but scarce banks o' Loch Fyne

- Published

Banks face a tougher fight closing branches in remoter rural communities such as Inveraray

Donald Clark is off to France soon.

From there, broadband means he can keep an eye on business back home. He's the fifth generation of Clarks in 160 years, to own and run the George Hotel, on Inveraray's Main Street.

I meet him as he surveys his olde world restaurant from the end of the bar, with its exposed timbers, low ceiling, flagstone floor and log fire, telling me that this year, from France, he's going to keep an eye on business... across the road, at Royal Bank of Scotland.

That's because he's one of the main figures in the fight to stop the closure of the bank's village branch. The George Hotel and the Clark dynasty have banked with it for over a century.

Disputing the bank's reckoning of few customers regularly using the branch, Donald Clark says his hotel's security camera can capture Royal Bank's footfall and give him a more accurate figure.

This is one of 62 branches earmarked for closure in Scotland, about a third of the total network.

The RBS Inveraray branch was earmarked for closure, along with more than 60 others in Scotland

South of the border, nearly 200 mainly rural branches of the bank's bigger high street brand, NatWest, are also being closed.

Royal Bank of Scotland, as a brand, is being confined to its homeland, as it has a bit of an image problem. That £45bn bailout and the decade-long nightmare of what it prefers to call "legacy issues" hasn't dented customer numbers that badly.

But when the bank asks customers if they would recommend it to a friend - which is a standard industry performance indicator - on balance, NatWest gets the thumbs up, but Royal Bank of Scotland doesn't.

That bailout led to majority ownership of RBS, and that is one of the reasons why the campaign to stop branch closures has got such traction.

Others have held back from trying to get ministers to direct its lending decisions, but on branches, it's different. The public - some of them - want to use the leverage of ownership.

But why in this case? One reason is the rural bias of this round of cuts. Rural communities are far better at mounting this kind of campaign than city types and suburbanites. They've seen their branches lopped off in previous waves of closures, and grown used to the conversions into cafes and bars.

Rural branches can more readily demonstrate inconvenience of reaching the nearest branch.

So it is clearly an opportunity for the Scottish National Party, allied with trade unions. With branches doomed in the west Highland constituency of the SNP's Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, he saw a campaign and he went with it.

Mr Blackford used to be a very successful asset manager with Deutsche Bank. In that role, he would have marked down any company reluctant to cut costs in underperforming assets. But as a politician, he perceives this as a company with an obligation to be present for rural communities.

Falling footfall

The campaign has had a victory, at least of delaying closure. In early February, 10 of the 62 Royal branches - the ones more than nine miles from the nearest alternative branch - were given another 11 months to prove themselves.

Campaigners can keep the petitions coming, and count the footfall, but the challenge is also to see if they can raise the throughput of transactions.

That's because Royal Bank's case is that it is going where the customers are. Footfall has much diminished. Transactions are negligible in some branches, as customers have flocked to online or mobile banking. It's claimed the busiest NatWest branch is now the Reading to London commuter line.

RBS, in common with other banks with brand networks, has an industry-wide standard for closures, drawn up by a financial services troubleshooter from Dumfriesshire, Prof Russel Griggs.

It requires at least 12 weeks' notice, clear reasons given, as much data as commercially possible to back up the reasons, and plenty of information and support on where customers can access bank facilities after the closure.

Yet I'm told, unofficially, that a significant proportion of visits to branches are by people making a social call. Having a mobile bank for an hour a week is no substitute for a regular blether with Catherine or Heather at the Inveraray branch.

And although Royal Bank is offering a platoon of digital finance trainers, I'm told they won't get far at the sheltered housing complex.

Budget crosshairs

Don't assume this is only about older customers.

I asked others in Inveraray, and got a mixed response, though mainly one of resignation. Michael Thomson at the fish and chip bar, minding the fryer for his dad, doesn't trust banking online. Nor indeed does he like banking in solid traditional granite and mortar. He prefers cash.

At the newsagent, the shop assistant tells me there's no need for Royal Bank. She banks online with TSB. And when she tries to say what she thinks of the RBS bailout, she quickly becomes lost for words of indignation.

I'm too late for the apothecary opening hours or the heritage sweet shop. (This is a very old-fashioned kind of town, or maybe its appeal is to old-fashioned day-trippers from Glasgow, and set jetter fans of Downton Abbey, come to see the Duke of Argyll's castle where the cast went on a Scottish shooting break.)

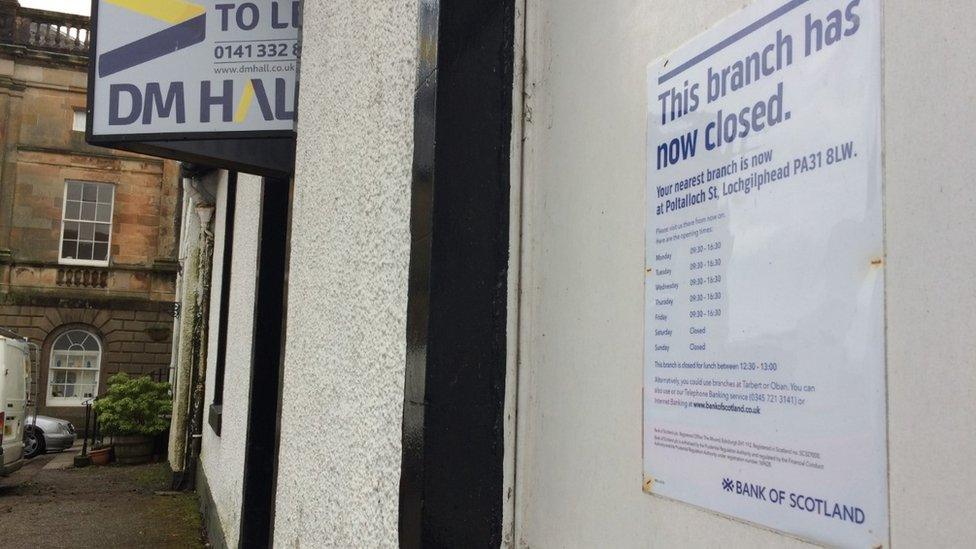

Bank of Scotland shut its Inverarary branch in late 2016

But back here in 2018, Alexander Gillespie, purveyor of "famous homemade pies" among other butchered comestibles, is across the road from the former Bank of Scotland - another of Edinburgh's financial brands tainted by the meltdown of nearly 10 years ago. That branch shut its doors in November 2016 with little attempt to save it.

It's "to let", and a sign in the window directs customers a half-hour's drive to Lochgilphead if they wish to use the nearest branch.

Mr Gillespie recalls seeing footfall of maybe two or three Bank of Scotland customers on some days. And he's not that bothered about Royal Bank either.

At Loch Fyne Whiskies, I find Steve Smeaton in a particularly good mood, as they've just sold a £10,000 bottle of single malt to a collector in Newcastle.

He remains remarkably cheerful as he portrays the plight of RBS within the broader picture of decline for the village that this 34-year-old calls home.

The community hall is derelict, the police station's closed, the Bank of Scotland branch likewise, the tourist office is earmarked for shutdown, the pier is fenced off as unsafe, and have I seen the state of the roads?

Even the public toilets - occupying a prominent place on the seafront, and a welcome sight to many a traveller on the epic A83 - have been in the crosshairs of budget-cutters at Argyll and Bute Council.

"4G?", laughs Steve about the mobile connectivity. "I can't get 1G here."

(The tourist office, incidentally, is one of 39 - along with Campbeltown, Dunoon and Tarbert in Argyll, due to close by October 2019, leaving the nearest "high impact hubs" in Oban or Balloch, at Loch Lomond).

Heartless giant

Like others, Stevie says cash handling or cheques will have to be handled at the Post Office, a counter in a general store used by several banks to dispense their services, hiding its modesty away from the elegant Georgian attractions in this, the Duke of Argyll's back yard.

I'm told that the banks are soon to co-ordinate their Post Office offering, so that customers are clearer about what services it provides. Its currently a confusing hotch-potch, leaving people confused on both sides of the counter.

This tale could be portrayed as a simple narrative of a giant, heartless bank turning its back on customers, and on the taxpayers who bailed it out of its own greed.

Yet it's not quite that simple. RBS is adapting, as companies have to do, to its customers' choices, while fulfilling the instructions of its owners - that's all of us - to get back into profit.

Nor is this a tale of an Argyll village in a sorry state of disrepair and decline.

Inveraray is a wee gem of a place, a loch-side Georgian treasure, with lots going for it. But it's losing many of the built institutions that have made it feel like a community, and it doesn't see what, if anything, will replace them.

* You can listen to a broadcast version of this article on BBC Radio 4's From Our Home Correspondent.