Selling news: Eyeballs on the prize

- Published

They dreamed the implausible dream. The plan to hire 800 staff for a new Scottish news publisher had got as far as hiring some journalists for key roles. That's right: eight hundred, for national coverage as well as hyper-local.

This week, it seems, the funders had a bracing dose of reality about the state of the commercial news media, and pulled out. Mission Implausible imploded.

This came ahead of the latest results from Johnston Press. The Edinburgh-based publisher of the 'i', The Scotsman, the Yorkshire Post and nearly 300 more local titles.

It gave a reminder of the problems news publishers face with advertising, particularly classified. Like-for-like advertising revenue during 2017 was down 13.5% on the previous year, and less than half of the firm's £200m total revenue. Digital ads may be growing from a low base, but they're not surging any more, and account for less than a tenth of total revenue.

De-duplicated

One of the key problems is that advertisers struggle to figure out how many eyeballs they're reaching when they advertise with news publishers. The publishers have struggled to give them reliable figures.

And the work of the publisher's own organisation, the Audit Bureau of Circulation, mainly serves to underline the dire problems they've had in trying to hang on to print sales.

Firing their online and mobile content into the ether, without much clue about its reach may be about to change, with the dawn of the PAMCo era.

This week saw the first publication of a new industry "currency", designed by the news and magazine publishers along with the advertising industry. It should give a vastly improved set of figures for readership and audience.

This replaces the National Readership Survey, by throwing the net wide to find out the reading habits of a representative sample of the British population.

With 35,000 face-to-face interviews in people's homes carried out by Ipsos Mori, the data is allied to a digital read-out of browsing records from data analysis firm ComScore.

Then, with a splendid new bit of jargon, the data is de-duplicated, to ensure each reader is only counted once.

Of the 35,000, some 5,000 accept an app in their electronic devices which tracks their reading habits in a lot of detail, and much more reliably than depending on their memory of what they've seen and who published it.

This has been a considerable commitment for the industry. While publishers have been slashing costs, Simon Redican, chief executive of PAMCo, the Published Audience Measurement Company, says it has cost £35m over the past five years to get to the point of the first figures being published. With quarterly publication, it will continue to cost a bit.

Glossy and aspirational

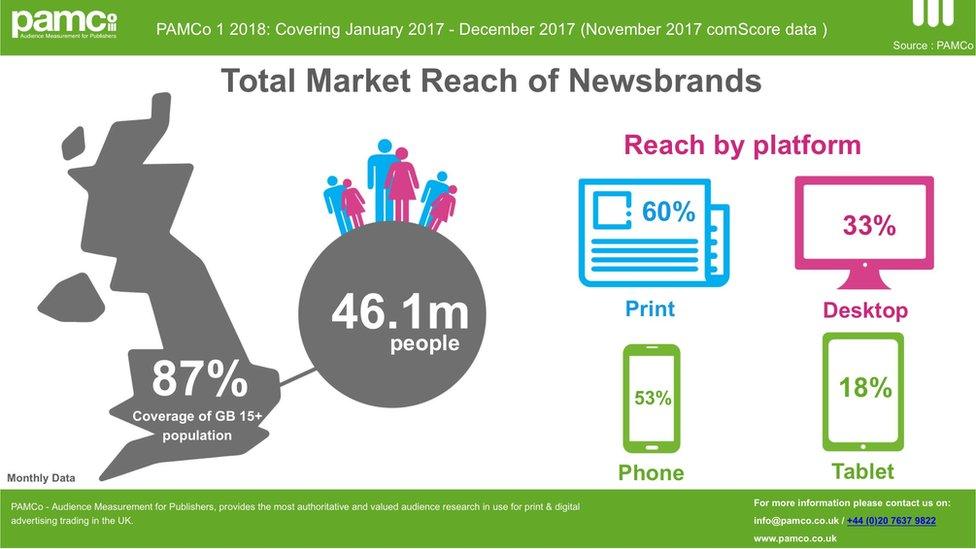

So how do the results look? And what do they tell us? They provide, for the whole industry, and for individual titles or news brands, a combination of figures for the number of people at least connecting with their content over the course of a day, a week and a month.

They show what share of that audience is engaging with print, how many on desktop, tablet and mobile.

There's a breakdown by gender and broad age group, offering also a count of households with children, a profile beloved of advertisers.

They don't tell advertisers or publishers the relative value of these electronic and print media. That's for them to figure out, but it's a reasonable assumption that someone relaxing with a newspaper is more engaged than someone browsing, at speed, on a small phone screen, while on the move.

That may seem obvious, but the advertising industry is still trying to understand the relative values of a display ad in an aspirational glossy magazine versus an irritating pop-up while you're trying to read a news article, urging you to buy something you bought last week.

Young insights

And what do the figures tell us? The big picture is news publishers reach 91% of the population aged over 15 at least once a month.

"What's really interesting," says Simon Redican, "is that, against expectation, reach of publisher content among young audiences is high, with 93% of 15 to 34 year olds viewing published content each month. We are confident that PAMCo will reveal further insights as users explore the data."

So that's a reassuring start for those who thought younger people have gone elsewhere with their media choices. From that younger demographic, 15m engage with at least one news publisher's content in a month, while that's true of 31m aged above 35. The daily engagement is more skewed towards the older age group, by 7.5m to 18.8m.

Overall, 48.1m people consume at least some published news content over a month. Of that, 73% will read a newspaper at least once. Some 55% will connect by mobile phone: 36% on a desktop, and 19% on a tablet.

You can break that down to look within segments of the so-called "proven" news media, which is the bit some people call legacy or mainstream, and which does not include either broadcasters, nor broadcasters online offering (such as you're currently reading) or radio.

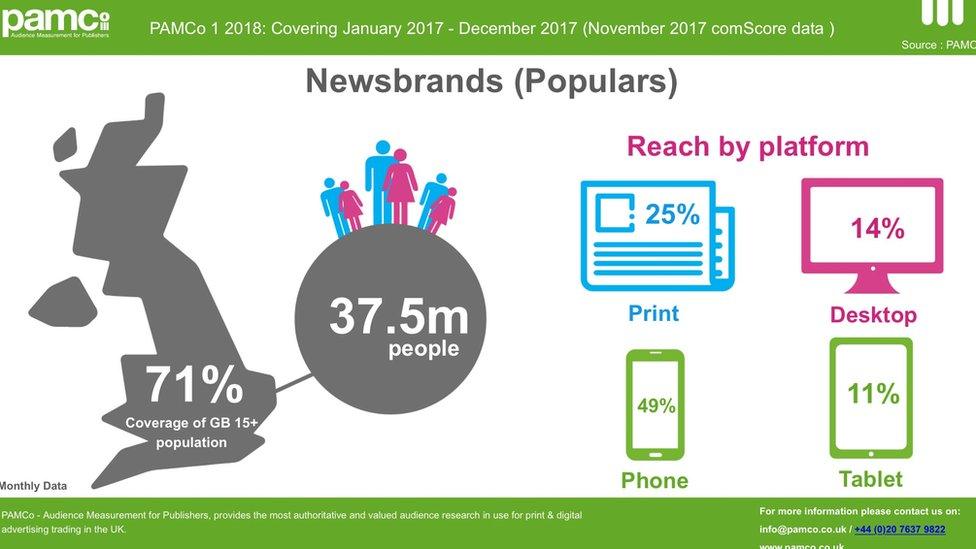

While "quality" includes the titles we used to call the broadsheets or heavies, "popular" includes mainly red-tops led by The Sun, The Mirror and Daily Record.

What that shows is that 37.5m British people connect with that output, or 71% of the adult population. Nearly half see something from them on their phone, and quarter see it on print. The desktop computer is the way in for 14%, and the tablet for 11%.

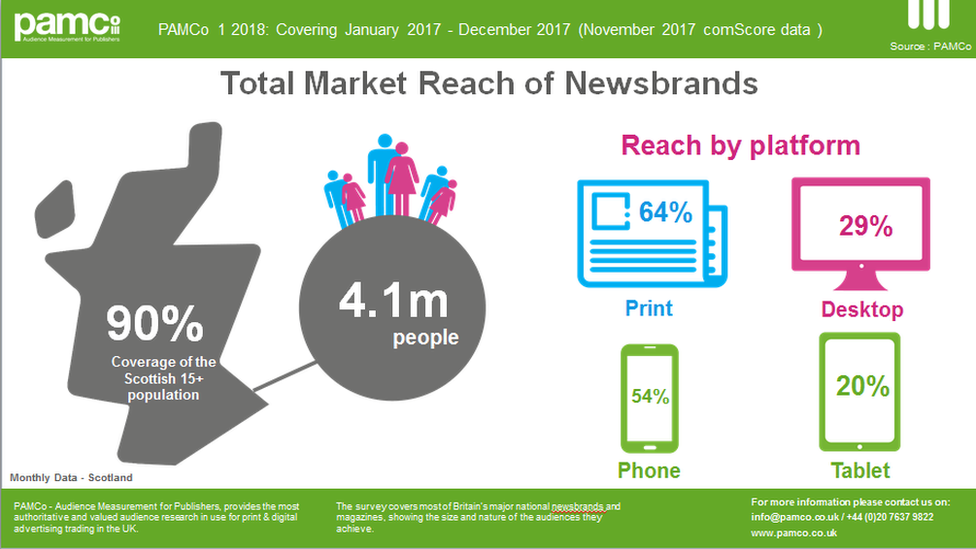

The figures also drill down to the Scottish level, and to those commercial news brands which are based in Scotland - including The Courier, Press & Journal, The Herald, The Scotsman, the Daily Record and their Sunday stablemates.

The overall reach of news brands, including London-based titles, suggests Scots are less likely to pick up a paper (64% in a month, compared with 71% across Britain), but nearly as likely to access news on their mobile phones or tablets.

What, then, of those Scottish titles? They're used on a monthly basis by less than half the adult population, or 2.2m people.

More than quarter read a paper, 22% access them on a phone, 8% on a desktop and 6% on tablets. That suggests the Scottish publishers are not offering as attractive an experience on screen as others from London. It shouldn't be that big a surprise. It's expensive to do so, and some publishers don't want their screen offerings to take away from paper sales.

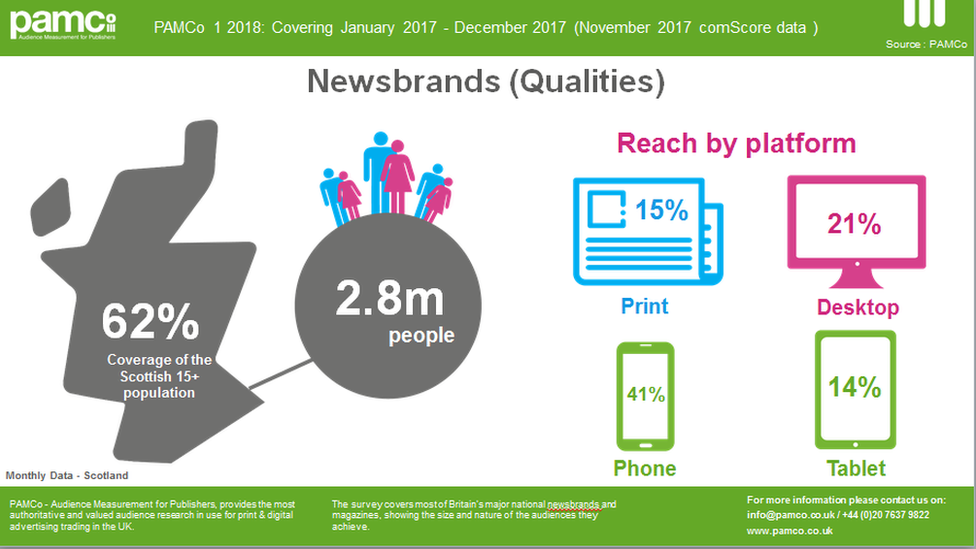

You can also break down Scottish audiences by segment. Instead of looking at the 'popular' category, the "quality" brands, including those edited in London, tell us that the higher price pushes people towards reading them on desktops and phones.

Only 15% of people access them in print over a month, while 41% see their content on phones, 21% on desktop, and 14% on tablet.

Screen saver

How, then, do individual titles and brands compare? There's a lot more to learn from this data than can reasonably be reported here.

But to give some examples, the British figures show us The Times reaches 8.1m people per month - 5.4m in print, 2.6m on phone screens. It has a subscription paywall, so it's no surprise that the numbers are well below those which are offered for free online and on mobile.

The Independent has no print edition now, but it reaches 20.5m people per month, according to PAMCo. Of them 5.2m are on desktops and 14.8m on phones.

The Telegraph and The Guardian, from different political perspectives, have similar figures, totalling 23.7m and 24.8m respectively. For The Guardian (including its Sunday sister, The Observer), 16m of those are on phones.

In Scotland, these big brands overwhelm locally-controlled publishers when the digital versions are included. The Guardian has a low daily sale of the paper, but a reach of 2.2m readers per month. The Telegraph and Independent are close to 2m each.

There are big numbers for what used to be known as tabloids; The Sun on 3m, The Daily Mail with a 2.6m reach, the Daily Record on 1.7m. The Record reaches more readers in print, while selling fewer than The Scottish Sun. But it has a far lower reach on phone screens.

Scotsman tablet

Finally, the Scottish city titles. The Dundee Courier and Aberdeen Press & Journal have lower smart phone figures than print, with a total reach of 533,000 and 459,000 respectively.

The Scotsman has a particularly poor daily reach in print, but according to PAMCo, it does significantly better over a month, at 281,000 readers of at least one paper edition. Because it offers its digital content for free, it can claim a reach of 901,000 in Scotland in total.

It's Glasgow rival, The Herald, has a paywall though it allows a small number of free articles each month. So while it reaches 339,000 in print per month, its numbers are lower than The Scotsman on tablet and phone. Along with the Sunday Herald, its total reach is 856,000.

You can probably see how these figures are reassuring publishers whose own industry figures register dismal average daily print sales of well below 30,000. The challenge, now that these new figures are out, is to use them to transform these papers' advertising performance.

And to industry insiders, they also provide an alternative to relying on Facebook and Google - these days treated with more suspicion in their use of data - to provide much of the understanding of advertising reach and performance.

- Published17 April 2018