Oil's up: What does it mean?

- Published

There's no magic price for oil at which investment is switched off or on, depending on the direction of travel.

Investment depends on each project and its break-even point, and no two oil fields are the same - least of all those that require drilling offshore.

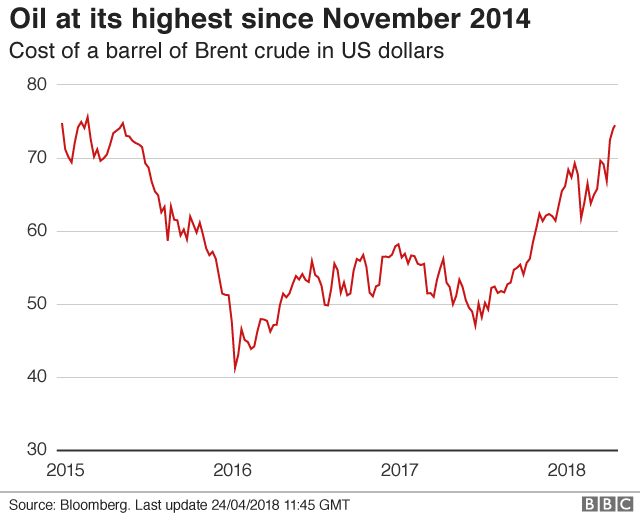

But at $75 a barrel, and on an upward trend, this seems a milestone at which to catch some breath and ask a) what's going on with the market for Brent crude? And b) what are the implications?

So first, what's going on? That's simple, perhaps deceptively so.

It's about our old friends, supply and demand. The latter is rising with economic growth, notably in Asia, but around the world.

Growth is not as closely aligned to demand for oil as it once was. But in India, for instance, development means a big boost to industrial production, demand for electricity and transport.

Symbolic of India's economic position, Saudi Arabia announced this month it is investing big in a refinery and petro-chemicals complex on a beach resort south of Mumbai. Ratnagiri will be one of the world's largest, processing 1.2 million barrels per day.

Saudi Aramco (state-owned while aiming to float) is taking a 50% stake in the £32bn ($44bn) project, while a consortium of state-owned energy firms in India own the other half.

Choke point

Supply is a more complex picture.

American stocks of oil influence the market, and the official numbers are expected to show they've fallen. That puts upward pressure on the price.

More significant in the longer term, the Opec exporters' cartel, working with non-member Russia, has been holding back on production in order to pull the price up. Saudis are among those straining at the loss of market share, particularly to Americans.

The market gyrated a bit last week when the Saudi oil minister said the rising price didn't seem to be doing much harm to demand, so he reckoned out loud that oil at $80 to $100 might be a possible sustainable target zone.

The Saudi government has, remember, a war to fight. And hostilities with Yemen, partially as a proxy for Iran, are one of the reasons for markets being nervous about security of supply. The Straits of Hormuz are an oil supply choke point which could also be a flash point between Saudi and Iran.

After the Saudi minister had hinted, Russia's energy minister counter-hinted that the constraints might come off the cartel, which would push the price down again. His comments did precisely that.

'All over the place'

America is the most dynamic part of the supply story, for two main reasons.

Fracking technology extracts oil and gas for a limited period before new rock has to be fractured. It's a repeated process, and if, as in 2014-15, the price drops, the process is stopped.

Only when the price rises again does fracking restart. That's what is happening. America is producing more oil now than ever.

The other unpredictable dynamic sits in the Oval Office. Donald Trump wants to break from the Iran nuclear deal, which would involve a return to sanctions on Tehran's oil exports - that is, a cut in its supply into the world market.

Donald Trump wants to break from the Iran nuclear deal, which would involve a return to sanctions on Tehran's oil exports

The US president tweeted last Friday: "Looks like OPEC is at it again. With record amounts of Oil all over the place, including the fully loaded ships at sea, Oil prices are artificially Very High! No good and will not be accepted!"

That, Mr President, is absolutely correct. Controlling supply and prices is precisely what cartels exist to do. That's the point of Opec.

And though oil prices may look too high from Washington DC, they probably don't look too high in mid-Texas or the Dakotas.

"No good" for oil users, but very good for oil producers. And when you say this "will not be accepted", we look forward, nervously, to finding out if this is another threat of trade war.

Put all that together, and the price of a barrel of oil delivered in three months has risen from a low below $30 at the start of 2016 to 150% more than that. However, the current price remains 43% below the peak in 2014.

Implications?

So what does it mean? Higher fuel prices? Well, not necessarily.

At the same time the oil price, measured in US dollars, has been rising, the US dollar itself has been weakening against sterling.

If like me, you'll find currencies easiest to understand by thinking of travelling abroad. If you want to vacation in America now, you'll be able to buy 12 more dollars for £100 than you could a year ago.

An Iranian oil facility on Khark Island, on the shore of the Persian Gulf

The same goes for dollar-denominated oil. A year ago, a pound bought you $1.28 on currency markets (without all those transaction charges). It now buys $1.40. That is, the pound buys 9% more in dollars than it did last year.

The other factor is that UK forecourt prices have a lot to do with tax rates. VAT runs at 20%, so it is as volatile as the price. For heating fuel, VAT is 5%. Fuel duty for transport is fixed, currently sitting at 58p per litre.

Take all that together, and the AA's price-monitoring tells us that the average price of a litre of unleaded fuel, at pumps across the UK, rose 1p between December and March, while diesel fell by 1p.

Gateway decisions

For Scotland in particular, it's worth watching for three different effects.

One is the risk of rising oil prices boosting costs for those who use fuel, in homes and in businesses.

For those reasons around sterling, there's no sign of inflation resulting yet. But where economies are already doing well, analysts are concerned that the rising price of Brent crude could push up prices more widely.

The other side of the coin in Scotland is the industry that extracts oil.

Investment decisions have to take big gambles on the future price of Brent crude.

In general, business plans don't like volatility or heightened uncertainty. It comes at a cost.

They prefer to see a reasonably stable price and a market environment which looks like continuing that for the foreseeable. They don't have that yet, but they'll like the upward trend for more than two years.

After a very harsh downturn, with the price slump from September 2014, much of the offshore industry has stabilised.

It has a number of big final investment decisions - the gateway or green light for a project - which are helped by raised prices and an upward trend.

Oil and Gas UK, the trade body, reckoned at the start of the year that at least 12 major investment projects were expected to be approved during 2018, worth around £5bn.

Tax take

So if there's more profit, there ought to be more tax revenue? Correct. But how much more?

Not as much as you would have found with other price revivals, because the UK Treasury has cut tax rates.

The main tax take is at 30% of profits. The Supplementary Charge was cut in 2016 from 20% to 10%. And the Petroleum Revenue Tax rate, levied on profits from older fields, was cut from 35% to zero.

The Office for Budget Responsibility last month raised its estimate of what the tax take might be as a result of the rising price, as it has had to do repeatedly.

It was a sharp increase, but to a level that remains low by previous standards - up from £500m this year to £900m.

Tax revenue from oil and gas is expected to average under £1bn annually for the five years of its forecast, which assumes the price of oil and of gas will fall again in the later three years. Production and profits are then expected to continue their decline.

For the purposes of arguing the case for Scottish independence, a geographic share of that tax revenue is dwarfed by the scale of the public sector deficit calculated by Scottish government statisticians in their annual expenditure and revenue tables.

Likewise, for those who want a national oil fund, less than a billion pounds per year might be nice to have but wouldn't go far.

That said, they are brave people who stick their necks out with assumptions about the oil price five years ahead. Sometimes, however, economic forecasters have nowhere to hide.

- Published24 April 2018