All the print that's fit for news

- Published

The Sunday Herald has published its last edition, bringing back memories of when it began, at the dawn of devolution.

Its demise has more to do with Scotland's political rift than with poor sales

Meanwhile, The Scotsman's sales are down 20% in a year. Even digital advertising is in decline

Its owner, Johnston Press, this week updated investors on its looming crunch point, if it can't secure finance.

The Sunday Herald ceased publication on 2 September after 19 years

And so, farewell Sunday Herald, published for the last time this weekend, with a "souvenir edition". This covers much of what it has achieved, but not much about why it's going.

This is personal. I joined it as political editor in summer of 1999, six months after it launched into the new dawn of devolution.

It was a bold and ambitious project, for which launch editor Andrew Jaspan deserves top billing. He had been bold and ambitious before, as editor of Scotland on Sunday.

Among the skills he brought to those weeklies (less so when he went south to edit The Observer) was the building of strongly-bonded, motivated teams of young journalists, with encouragement to reflect a young, modern Scotland, and to set Scotland in a global context.

The Sunday Herald had terrific design - a factor too often under-appreciated in news publishing - for which much of the credit should go to its second editor, Richard Walker.

It had style. It makes a big difference to see your writing that well presented. Occasionally, I admit, the presentation was somewhat better than my article. There was no pig to which Richard could not expertly apply lipstick.

We worked on the latest big thing in desktop computing - the iMac. We were so modern we had actual email addresses next to bylines.

The website was an integral part of the news offering, rather than, in other papers, a barely-understood add-on which would later threaten to devour the print industry.

Dead Man Writing

Much of it was on a shoe-string. Some staff clubbed together to finance a water cooler, but only for those paying the monthly fee. Eventually, management agreed to fund one for everybody.

Although resources could be meagre, it didn't hold back with its world view.

Foreign editor David Pratt roamed the world's war zones on its behalf, with bravery, insight and a camera. Rob Edwards, now pioneering crowd-funded journalism at The Ferret, put a strong environmental stamp on its image.

I sought to shed light and context on the febrile atmosphere in the early days of the Scottish Parliament.

After five years, Paul Hutcheon took over, with a flair for dogged digging where he wasn't wanted, and he can claim several prominent scalps. His mission was helped by the introduction of the Freedom of Information Act.

Neil Mackay, later to become the third editor, exposed extraordinary stories about Northern Irish paramilitaries. Some great feature writers roamed across both Scotland and serious popular culture.

'It was a blast'

Signing up the song "It's My Life" by Dido for a TV ad - before she went big and when there was money for such extravagance - underlined that this newspaper was cool.

The readership was never big, and was focused on a few postcodes not far from Glasgow's Byres Road. But it was a newspaper that mattered. It punched above its weight, with a reach far beyond its core.

It was audacious in inviting great writers to contribute. Peter Ross, a features editor, and a superb writer, recalls "it was a blast sometimes - it felt like you could just do stuff" - Donna Tartt on Robert Louis Stevenson; on boxing, Budd Schulberg, who penned "On the Waterfront"; John Byrne was commissioned to paint Billy Connolly.

A memorable columnist in the early years was Jonathan Wilson - "Dead Man Writing" - sharing the view from terminal cancer, often with warmth and humour. He died in 2002, aged 31.

The paper took a hard line against the neo-cons in Washington under George W Bush, after which American TV news talk programmes - in a more innocent age - would look to the paper and its Westminster editor, Jim Cusick, to speak for liberal, anti-war Europe.

Sunday sales

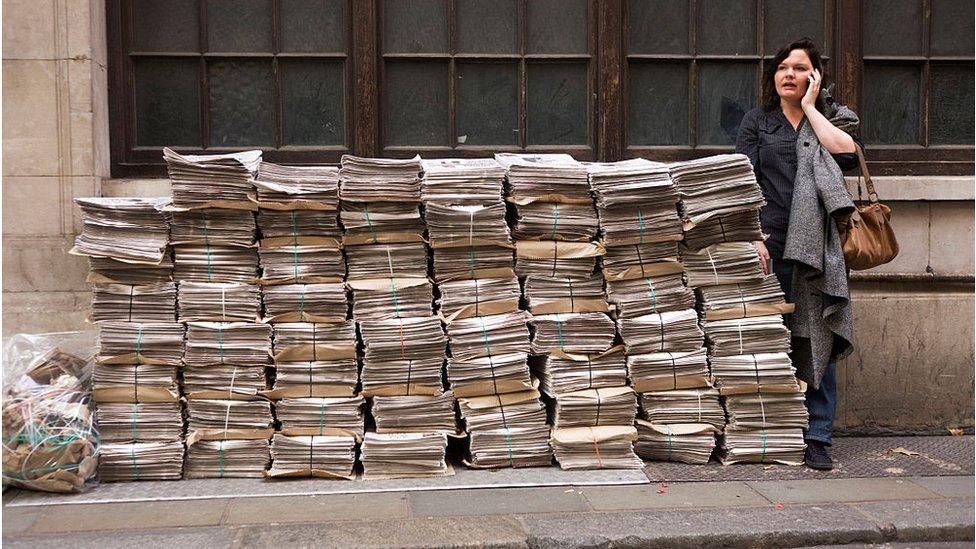

And now, it's gone. For years, we've been predicting a slimming of the range of titles on the news stand.

Yet for Scotland, there's little change to the number of titles - more to the quality and width of what can be achieved on ever-tightening budgets and with fewer journalists.

In the case of the Sunday Herald, improbably, it's being replaced by two titles.

What that signifies says less about the state of the industry than about the constitutional rift running through Scotland.

Its publisher, Newsquest, will now produce two papers on Sunday - The National extending from six days a week for pro-independence supporters and The Herald for, er, well, the rest. They're not all pro-union. Far from it.

Politics is often seen, by people interested in politics, as being the key to understanding the sales performance of newspapers. That forgets how many readers turn first to the sports pages.

Stramash

Sales of The National and the Sunday Herald - both a long way below 20,000 - tell you that circulation does not correlate to a political posture.

And while there is a market to be tapped from packaging news for the true believers in a cause, the pro-independence slant of the Sunday Herald also demonstrated one of the weaknesses when journalistic judgement clashes with the interests of the cause.

Earlier this year, the Sunday Herald infuriated a section of the pro-indy movement by prominently publishing a strong but controversial picture. That appeared to show a small pro-union demo in Glasgow on a par with the much larger pro-independence march that day.

The digital stramash that followed, and the pressure on the tiny number of staff remaining in the Renfield Street office, appears to be one of the main reasons it is now closing.

Looked at another way, a paper that is full-on for a political cause isn't going to appeal for long to non-believers.

The business case for the Sunday Herald in 1999 was that The Herald was missing the opportunity to retain its daily readership at the weekend, and the glossy magazine advertising opportunities that went with that.

The titles always had a different feel to them, and the Sunday Herald was not as successful as it should have been at attracting weekday Herald readers. Since declaring for independence, that gap in style and substance has grown wider.

The Scotsman

While the Sunday Herald's print circulation has fallen, The Scotsman is notable for falling faster - down 20% in January to June, when compared with the same period last year.

With just over 16,000 copies circulating each day, more than 3,000 of them are given away free at airports and hotels.

It has gone down the path of offering its articles for free on its website.

It can show off a big number for its average daily online readers - at nearly 138,000 and rising - but that is undermining the print product and the advertising revenue that goes with getting eyeballs to printed pages.

Ads online make far less (and in the case of The Scotsman, they are very irritating).

Across the 200 or so titles owned by its Edinburgh-headquartered owner, Johnston Press, there was an admission last week that even digital advertising revenues were going backwards, by more than 7%, and the total by 15%.

The reason given was changes to algorithms and news feeds at Facebook and Google. This is not a business environment in which editors have much control of their fate.

On classified adverts, revenue was down a precipitous 28.5% in only a year.

'Extremely difficult'

The new chief executive says trading is "extremely difficult", conceding that the dire financial straits Johnston faces means that there is next to no capital to invest behind the products.

The positive news is its recent acquisition of the 'i' newspaper is generating more revenue. A £6m profit for the first half of this year, on £93m revenue, was almost all down to the 'i'.

The dominant negative news is that the company is in intensive care as it looks down the barrel of a deadline in June next year, when it has to find a way of refinancing £203m of debt.

Attempts to reach a re-financing or re-structuring deal with bond-holders and pension trustees (with a pension deficit of £40m) have been dragging on for nearly a year, with no sign of progress.

The share price is on the floor. The market valuation of the company, its brands and its printing presses comes to less than £5m.

Something dramatic is going to have to happen at Johnston Press in the next few months, through re-capitalisation or collapse. It has made clear that without a deal on finance, it can't go on.

Titles may be salvaged, but after years of under-investment and such poor print sales, The Scotsman has the look of the most vulnerable print title on the news stand.

- Published3 September 2018