Growing firms: Mend the gap

- Published

The Scottish government is working towards a state bank, to intervene and invest in strategic priorities.

The British Business Bank already fills some of the gaps left by the more risk-averse market lenders, but is less strategic in what it seeks to do than the Scots plan to be.

After four years building up its supply of wholesale funds through retail lenders, Lord Smith of Kelvin is leading the push to stimulate demand, bringing him to Glasgow to meet small business leaders.

Time was when government was meant to get out of "picking winners" and investing in private companies. It had, for too long, been associated with picking losers, and running into ruinously expensive commitments.

That time was when ministers could direct investment decisions and pay policy in state enterprises from steel to shipyards to coal to the electricity providers and telecoms.

In Britain, that sort of intervention got a bad name. The Thatcher revolution was all about "rolling back the frontiers of the state" to let the market decide.

Well, those days are gone now. It's been noticed that other countries have done rather well by investing and by government lending - particularly where it does so in the strategic sectors where it is reckoned that the country has the makings of a comparative advantage over others.

The Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) is being set up by the Scottish government to take a more interventionist role. It's been talked about a lot, and taken a long time to reach the starting gate, though bits of what it does have been done by Scottish Enterprise for some time.

Mission possible

A consultation on the SNIB got under way this week. Finance and economy secretary Derek Mackay bigged it up as something with "the potential to help transform Scotland's economy". It will be long-term, patient and mission-oriented.

That's a reference, first, to the short-term shortcomings of conventional lending and investing in the financial marketplace, at least in the UK.

Being "mission-oriented" sounds like the influence of Mariana Mazzucato, the London-based economist who is an economic adviser to Nicola Sturgeon, who argues strenuously for recognition and enhancement of the role of the state as an investor and shaper of the economy.

I interviewed her, external earlier this year.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato backs enhancing the role of the state as an investor and shaper of the economy

Also advising the European Commission on mission orientation, she believes that government should set the big objectives, as President Kennedy did when he set the target of putting a man on the moon by 1970.

The missions in mind include "transitioning to a low carbon economy; responding to an ageing population and wider population health; and promoting inclusive growth through place-making and regeneration". In the consultation, you're invited to add to that list.

"The Bank will serve businesses who wish to innovate and grow but find the traditional routes to finance challenging," said Derek Mackay. "By providing a single point of access to investment, and adopting a strategic focus and risk appetite that is different, the Bank can fuel the economy and catalyse additional private sector investment."

Business finance in numbers:

£191m of equity investment in Scottish companies in 2017, up 100% on 2016

121 equity deals done last year in Scotland, up 48% in a year

£2m: Average equity deal for companies in Scotland last year, up from £1.5m in 2016

Software (24) and industrials (21) were the two sectors with the highest number of equity deals in Scotland in 2017

53% of equity deals in Scotland involved government funds

British Business Bank supports £467m of finance to Scottish smaller businesses

3,334 Start-up Loans in Scotland, with a value of £23.3m, since 2012

Source: British Business Bank

The Scottish government is committing £2bn over 10 years as initial capital for the SNIB, intended to lever in lots of additional private investment.

And while there may be widespread agreement that this seems a sensible way to go, there are some politically tricky questions - how much should this state bank pay its top executives, and with what bonus structure, if it's going to get financiers of a high calibre? And will all RSIB be constrained by the Scottish government's future policies on pay restraint for the public sector?

Crowding in

There are foreign precedents for this. KfW are the initials of something unpronounceable in German. European state aid rules are thrown up by British critics of Brussels, while they have been more imaginatively interpreted by other Europeans. Even in free market America, there is a government bank for supporting small business among other sectors such as housing.

And there are a couple close to home. The European Investment Fund has big British contributions, and also big British beneficiaries. At least the latter is going to slow to nothing much, under Brexit plans, though the deal - if there is one - may include a continued contribution from the UK.

There is also the British Business Bank, set up in 2014, but little known beyond around a hundred lenders through which it provides its funding wholesale.

Under Conservative ministers, the language of intervention in the market is a lot less prominent, and if there are sectors which are overweight in its lending portfolio, that's not by design but by coincidence.

It has become the largest venture capital investor in the UK. It operates, goes the blurb, where there is clear market need "crowding in and not crowding out private sector activity". That's to say: it is not in the same territory where mainstream lenders fund blue chip firms. It is seeking to identify areas where finance is hard to come by, often within the growth path of a growing company.

Start-ups

Much of its activity so far has been around ensuring a good supply of funds through these lenders. And 96% of lending is being carried out through channels other than the four big high street banks. Clydesdale is one of those that works alongside the British Business Bank.

The emphasis is shifting, towards more effort to stimulate demand for what it can offer. So it's going a bit more retail. On Friday in Glasgow, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were invited to hear what it does and to say what they want from it, alongside Scotland's lenders and fund-managers.

Those that don't yet exist are also welcome to take a nosy at what it's all about. It is in the market for loans of as little as £500 from its start-Up fund. That comes with some mentoring advice. The typical loan in that category is for £7500. In Scotland, 3,334 companies have been supported since that fund began in 2012 (it pre-dated the British Business Bank), totalling £23.3m in loans.

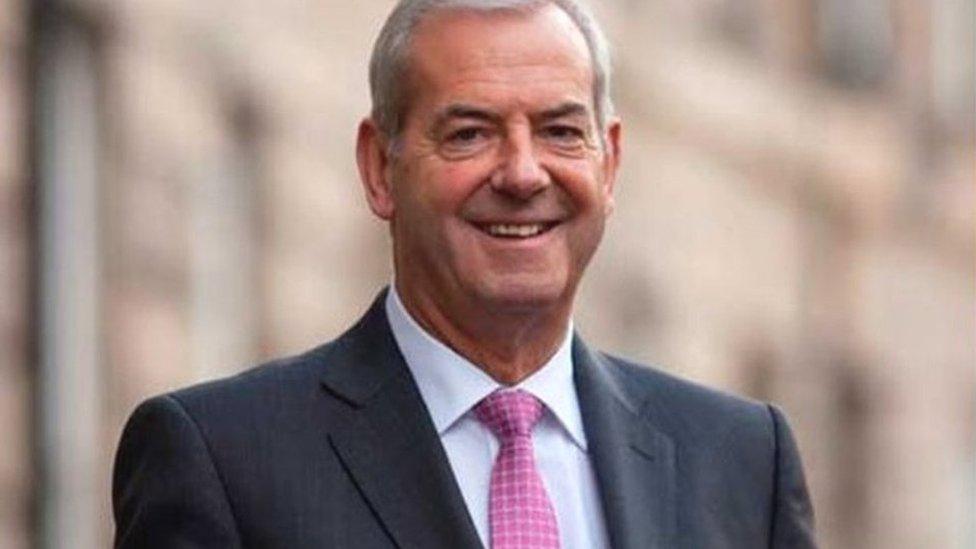

Presiding over the Glasgow bit of the roadshow proceedings was Lord Smith of Kelvin, sometimes known as Robert Smith and in his home city.

Lord Smith of Kelvin

An accountant and former fund management boss, he has occupied an astonishing number of chairs in Scotland; Weir Group, SSE, Alliance Trust, the Green Investment Bank, the organising committee of the Glasgow Commonwealth Games, the commission that bore his name which drew up the plans for devolving greater powers to Holyrood and, for the past year or so, the British Business Bank.

I met him ahead of the meeting with SMEs, to hear what he has in mind for this push into lending, where more stimulus is needed.

"The message is that there is finance available - risk finance, long term finance - available to small and medium-sized companies," he told me. "We're ensuring that's available through a whole range of providers. I want to hear from businesses and from financial advisory people: What are the impediments to help these small businesses get started and grow?"

Engine and Powerhouse

In Scotland, one of the stronger bits of start-up funding is the "angel" community - typically those with a few million available for risk investing in new ideas, who can put in not just their money but their expertise as experienced entrepreneurs.

This is a small enough country that they know each other, and can collaborate all the more easily.

Some 8% of UK angel investors are located in Scotland. Venture Capital funds, however, are hard to find north of the Cheviots. That tends to require a trip to London, or further afield, and it is perceived as a significant gap in the Scottish business growth support network.

The British Business Bank has given itself the explicit task of ensuring it gets out to the regions of England more, and creating networks of investing angels is one of the things it wants to do.

While Scotland has policy infrastructure in place, through Scottish Enterprise and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, the English regions need more of a helping hand.

So far, the Business Bank is working alongside the Midlands Engine, the Northern Powerhouse and a partnership set up for Cornwall and the Scilly Isles.

Patience is one of the virtues the British Business Bank wishes to emphasise more, just as SNIB wants to take a longer-term view than conventional lenders in the market place. So patient capital is being given a boost, with the intention of leveraging as much as £13bn from financial partners.

Get that right, and the hope is that the market for longer-term financing could be stimulated into activity without the need for government help. But that day is some way off.

"When we talk about patient capital," explains Lord Smith "a business goes for a number of years, it then needs more money to grow and become a very big company.

"What would be great for Scotland and the UK, if these small companies grew and grew and grew, and didn't sell out after a while for want of forward finance."

"In America, you'll find a third, fourth, fifth, sixth round financing. It's much more common that you'll find in the UK, and we're identifying fund managers in whose funds we'll place some of our money if they're patient capital providers."

The problem he identifies is a familiar one to watchers of the Scottish economy. Make your first three or four million, and it's tempting to get out and buy the yacht. That's one reason why Scotland has yachts, and not many medium-to-large home-grown companies.

"I think it's a mixture of a shortage of that third or fourth round funding, but also a mindset in entrepreneurs, says Lord Smith.

"I'd like to see they can grow their companies bigger and more internationally than they currently do.

"And yet in Scotland we've got one or two of these unicorns - going from start up to unicorns worth $1bn in a relatively small number of years. I'd like to see more of those, because that's what attracts investment in jobs, and the wealth of the nation."