RBS: the cost of crisis and lurking legacy

- Published

Royal Bank of Scotland has reported a modest third quarter profit, as it returns to something like normality, but it still has legacy issues.

Damage to its reputation looks more deep-seated in Scotland.

Ten years from the financial crash, a look back at the numbers is staggering. So now, is RBS ready for the next chapter?

The most striking feature of the latest set of figures from Royal Bank of Scotland is how ordinary they are. It's almost as if this is a normal bank, at long last.

Analysts may take issue with the size of third quarter profit and interest rate margins heading in the wrong direction, but £442m looks OK to us, the main shareholder, after all that it's put us through. At least the colour of ink is not red.

RBS is not yet out of the woods on the mis-selling of payment protection insurance (PPI). The bank has added £200m to the sums set aside already, taking its total to a staggering £5.3bn. Of that, £4.5bn has already been allocated.

At least an end to that nightmare is in sight, as a deadline has been set for claims to be made.

That £200m is a drop in the RBS ocean compared with the recent past, and it is in common with other banks that mis-sold PPI.

Stress tests

The normalisation of these financial results is most notable for the lack of legacy costs and notes of uncertainty about litigation and multi-billion dollar penalties.

The share price still looks dismal, however, and it fell further on the news that £100m is being set aside to deal with potential loan defaults as a result of Brexit. Other banks haven't felt the need to do that.

Ross McEwan, chief executive at RBS, has played down its significance, saying the loan book has been cleaned up recently.

So there's no reason to think RBS is more vulnerable to Brexit than other lenders, goes the argument - except for the fact that the retreat of the Royal Bank to the UK and Ireland has left it particularly vulnerable to shocks in those countries.

The scale of that vulnerability should become clearer with the looming stress tests. After they are over, Mr McEwan hopes to offload some of his excess capital.

He needs permission from the regulator, but the project is likely to involve a share buy-back. That's now very widespread in quoted companies, spending spare cash on shares in order to cancel them concentrates the ownership of remaining shares. That pushes up the dividend per share, and therefore their value.

Talk of paying a dividend has been theoretical for RBS until this month, when it made its first distribution since its meltdown, of 2p per share, or £240m. Most of that went to the Treasury, as it still owns 62%. Another option for the surplus billions of capital is to buy part of that Treasury stake.

Turmoil

The books may be repaired, and at vast cost, but as Ross McEwan has conceded, it could take up to ten more years to repair the reputation of RBS.

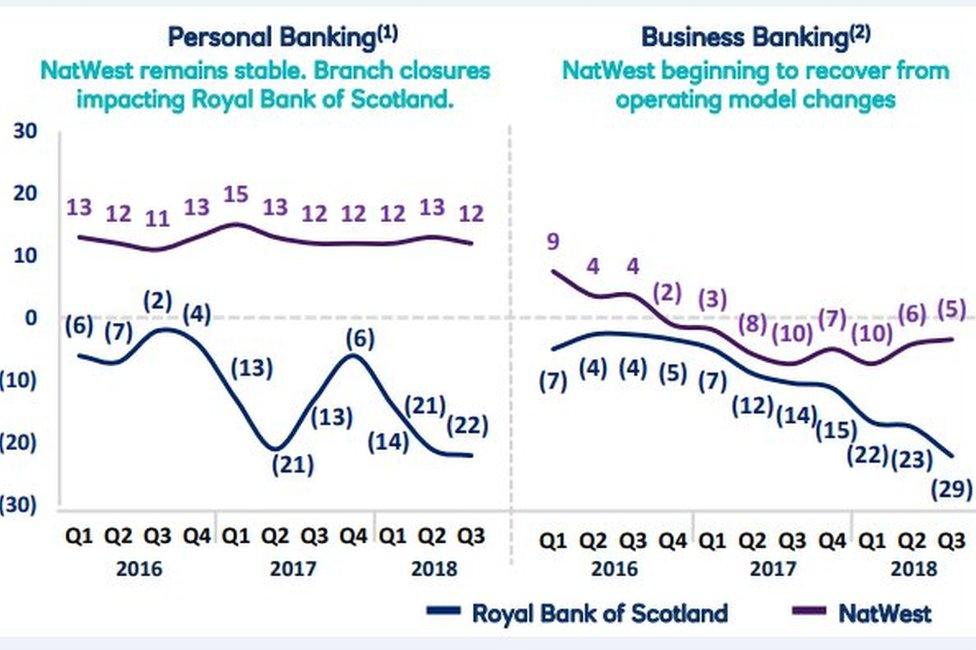

A measure of that is the Net Promoter Score - the industry-wide measure of whether customers would recommend their lender to someone else. Improving them is one of the key targets set by RBS bosses.

For the NatWest brand, that's healthily into positive territory. But for Royal Bank of Scotland, now largely confined to Scotland, it remains very negative for both personal and business customers.

Subtracting the positive promoters from those who would not promote the Royal Bank of Scotland has gone further into negative territory in the most recent figures, which the bank explains with reference to the publicity surrounding branch closures.

Linked to those closures, the move to mobile app banking continues apace. Nearly half of personal loans are now arranged digitally, and 60% of mortgage switching.

So yes, the legacy still lurks, but it doesn't threaten the future of RBS as it did. It can operate more as a normal bank, which its workforce (down 6.8% on last year, by the way) has sought to do through the noise and turmoil.

Loan arranger

Ten years on from the RBS meltdown, this seems a good point at which to reflect on how far it's come.

Its chairman, Howard Davies, has handily done that in a recent lecture. He noted that financial institutions ten years ago were failing for several core reasons. RBS stands out as a beacon of notoriety because it failed for ALL of those reasons.

So take your time, if you have some spare, in letting these numbers sink in. Over the ten years, the core operating bit of RBS made a profit of £65bn. But the reported loss accumulated to £63bn. That means that the total cost to RBS and its shareholders was £128bn.

That's more than five times the current capitalisation of the Royal Bank, Davies noted. And that doesn't include the £45bn injection of capital at the point of crisis.

Of that, £49bn was written off in loan provisions. Yes, forty-nine billion. That £100m set aside for Brexit pales somewhat in comparison. Within that, property and construction cost £20bn, and Ireland accounted for £12bn.

After a five-fold increase in its exposure to Irish property lending in only four years to 2007, "the property-related losses in Ireland were a more significant element of the bank's collapse than is generally understood," says Davies.

Risky traders

The cost of mergers and acquisitions, by which Howard Davies means ABN Amro and Citizens Bank in the USA, brought a bill of £30bn.

The lecture didn't offer a totting up of legacy and litigation, but there's been a lot there. The £5.4bn on PPI is one. There have been fines and penalties and litigation settlements.

The US Department of Justice was last with the big ticket items, levying a £3.6bn penalty for mis-selling toxic mortgage-backed securities in the run-up to the crash.

The subsequent mis-treatment of business customers by RBS's now notorious Global Restructuring Group rumbles on loudly, and has £400m set aside for it.

Restructuring costs have accumulated to £15bn. Reform of the sector required ring-fencing of the riskier, financial trading parts of the bank to separate it from the utility banking part. Recently put in place, that cost £1bn.

And there was a price to pay for the European Commission permission to use state aid in the way the UK Government did. At the time, it seemed reasonable that RBS should be told to shed subsidiaries and exposures, and reduce its NatWest dominance of the UK market for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs).

So it sold its payment system, WorldPay, for £2bn. That is now worth £8.1bn.

It sold Direct Line insurance division, for £3.2bn. The market capitalisation of that standalone company is now £4.6bn.

Challenger

The Royal Bank was also told to shed 5% of the SME market in the UK. In a moment of optimism, it was assumed this was "unlikely to be materially significant to shareholders".

This was correct in one sense: shareholders were getting no dividend, and continued to do so. But in any other sense, it was very wrong.

RBS carved out a large chunk of mainly English and Welsh business, then branded Royal Bank of Scotland. The intention was to revive its Williams and Glyn brand, and sell it.

But no-one was buying. It was too complex, especially the process of disentangling IT systems. So at RBS HQ, they set about floating Williams and Glyn. That too had to be abandoned. Total cost of that fiasco, much of it on abortive IT projects: £2.4bn.

RBS asked to be let off the hook on that requirement, which it has been allowed to do, but at another price. It has to hand over £775m to an independent body, which will distribute it to smaller, challenger banks, so that they can spend it on biting chunks out of RBS's business market.

Shattered

Howard Davies concluded, as you might expect, that this has got RBS to the point where it can be a viable standalone bank. There is evident concern that the failure to get back to the 500p mark in the share price (it's currently less than half that) will be an obstacle to the UK Government's share sales.

Howard and McEwan have both been softening up public opinion, by pointing out that the £45bn bailout was not a conventional investment, but a means of saving the UK economy.

RBS chief Ross McEwan called the bank's latest results "a good performance"

The chairman's lecture hinted at one issue that would quickly arise at the point when the UK government sells its stake - a weak or undervalued bank would be vulnerable to predators. If it's not weak, then it's probably undervalued, and vice versa.

The other prospect he raised was that the election of a Labour government, before the Treasury relinquishes control, would leave Messrs Corbyn and McDonnell in a position to turn it into a state development bank.

That's if the Labour manifesto remains as the plans currently stand. The last election was fought on the pledge to shatter RBS into numerous regional banks, but that idea seems to have been dropped.

Horror story

On a personal note, a vote of thanks. I joined BBC Scotland and began my task of covering business and the economy on the same October morning that the financial catastrophe went into a market tailspin, pushing RBS into the hands of the Treasury, and Fred Goodwin into... well, where is Fred Goodwin? Has anyone seen him recently?

I'd like to thank those at RBS who have helped me understand their plight, and answered occasionally rude questions. The staff, very few of whom should shoulder any blame, have proven admirably resilient.

Thanks to them for developing a news narrative that has given business journalists lots to do over the ten years.

And thanks for providing us all with a a very, very expensive form of entertainment - the variety usually celebrated at Halloween.

- Published26 October 2018