Brexit and fish: Skippers, kippers and the creel thing

- Published

The Scottish Fishermen's Federation has been the most enthusiastic business group for exiting the European Union, but it now finds itself being set against the interests of the exporting processors and salmon farmers

It has been punching well above its weight, with Scottish Conservative MPs taking their cause to the political brink

The dangers on the horizon for the bigger boats include the vociferous lobbies of foreign fishermen, the competing case for Scottish exporters and a breakaway representing smaller boats, who see Brexit as an opportunity reset the dials on quota

Fishing is a small industry but has become a huge political issue

Brexit brings "a sea of opportunity" - so says the Scottish Fishermen's Federation, as it pushes for a clean break from Europe's Common Fisheries Policy, and wants to grab quota (fish landing rights) from foreign skippers.

But it's turning out to be more complicated than that.

That sea of opportunity is looking choppy. The deal struck by Theresa May carries the expectation that EU countries will negotiate access to UK waters, in exchange for UK access to EU markets. Nevertheless, the Scottish Fishermen's Federation (SFF) is on board for the PM's deal.

But how representative is it? I've been finding out more about the prominent role fisheries is playing in the Brexit debate.

This is a relatively small industry, so why has it become such a big deal politically?

EU countries are likely to negotiate access to UK waters

Partly it's down to lobbying power. The fishing community is concentrated in a few constituencies. It gets heard, and because of tight Commons arithmetic around Brexit, it's got leverage. Scottish Tories have aligned themselves, as Alex Salmond used to do when he represented a north-east seat.

The industry is seen as having a strong, clear line against EU membership. It was described as "expendable" by the British government when negotiating entry to the European Economic Community in the early 70s.

It's now seen as the most pro-Brexit industry, and most anti-Brussels. But when we talk about a fishing industry viewpoint, we're missing the growing complexity. There are different and potentially conflicting interests. Where would these conflicts become a problem?

'Daft and absurd'

This got tricky in the recent negotiations on relations with the EU after transition. The EU27 got what they wanted - annual negotiations, and access to UK waters tied to UK access to EU markets. So taking back control is possible, but excluding others from UK waters is likely to come at a cost. For the first time, farmed fish have been drawn into this.

None of the sectors like that link being explicit. They're agreed on that much. But if the Brussels view of fisheries prevails - and it's been voiced also in the past few weeks by President Macron of France - it would pit the fleet against the processors and fish farmers.

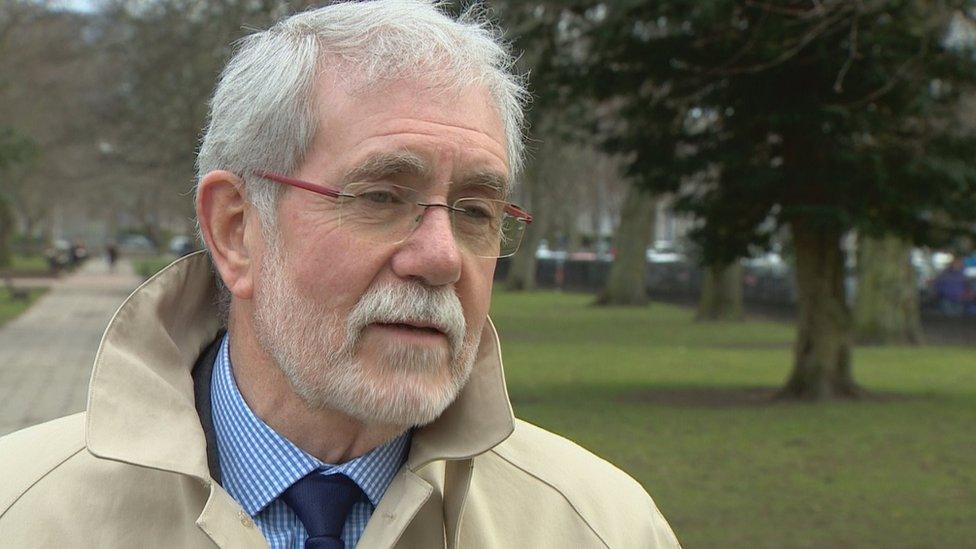

The fishing voice that gets heard most often is Bertie Armstrong, of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation. He highlights the 60% of fish caught in UK waters by foreign boats. He thinks future negotiations are going to see the UK being more successful than it's been recently.

Bertie Armstrong of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation highlights that 60% of fish caught in UK waters is by foreign boats

He says: "The trump card of 'you can't come in here and can't fish for anything unless it's on my terms' says every coastal state, and that'll be us. Then we have the strongest hand of cards. Mr Macron will will push as hard as they can for the status quo. But that would be absurd. That would be a daft thing for the government to agree to".

Daft and absurd, maybe, but it wouldn't be the first aspect of Brexit to merit those descriptions. It is what EU negotiators will want, and the British side should know by now that they are not to be under-estimated.

For countries such as France and Spain, as well as North Sea fishing states including Holland and Belgium, they also have highly concentrated fishing lobbies.

EU experts think the next round of negotiations, if there is not to be a no deal Brexit, will feature the demands of individual member states rather than the unified demands of the 27.

Filipino filleters

Academic experts on this reckon there's a reality check coming that the industry and Downing Street have failed to be honest and frank about the pushback that can be expected from other EU countries.

They say that the long-term relationship will require compromise. So if this is now going to be a tension within fisheries, let's look at the relative weight of the different parts of the industry.

There's fish processing with employment for 7,600 people, most in the north-east, including European migrant workers. It had output, or added value, of £391m two years ago, accounting for 0.3% of the overall Scottish economy. Export markets are important to it.

Fishing makes up a small percentage of the Scottish economy

In 2016 fish farming, including some mussel beds, generated £216m for the Scottish economy: accounting for 0.16 % of the total.

In terms of employment, aquaculture provided employment for 2,300 people, contributing 0.09 % to total Scottish employment. Many of these jobs are in the remotest communities of the west coast and Hebrides and the northern isles.

And the fishing fleet? It generated £296m in output during 2016: accounting for 0.2 % of the overall Scottish economy.

Many workers are not Scottish

It employs 4,800. That's one in every 500 Scottish workers, or it would be if they were Scottish, because quarter of deckhands in 2015 were from the Philippines and a fifth of engineers in the fleet also Filipino.

Workers from Latvia to Ghana also work on the boats. Some 28% of the offshore Scottish fisheries workforce is not Scottish.

The number employed fell in the 1990s, and in the early 2000s, when overfishing was more of a problem and a big cut in fishing capacity was implemented through the Common Fisheries Policy. But there was a much steeper decline in the numbers employed in the two decades before the UK joined the EEC.

With rising quotas, as stocks recovered, but with number employed down by 11% between 2008 and 2016, the value added per worker soared from £33,000 to £61,000.

Centre stage

So in accounting for less than a fifth of 1% of the Scottish workforce, and significantly less within the UK labour force, the focus on the fishing fleet, and the influence it is currently wielding, is well above its actual size.

"There are two sides to imports and exports," says Bertie Armstrong. "If we are to have exports into Europe hindered, what about us - the fifth biggest economy in the world - importing all those Dutch flowers, that French and Spanish agricultural products and wine, half a billion pounds worth of Danish bacon, 750,000 high quality German cars?

"All that's coming our way. So if they're going to cut up rough about trade for one cherry-picked industry, what about all the rest? There's a balance to be struck there. So we do not feel we're in a corner in these negotiations, and the UK government, as far as I'm aware, doesn't feel it's in a corner.

"What gives me some comfort. There hasn't been as much noise about fishing... ever. We're in the centre of the stage, along with Gibraltar, the backstop and freedom of movement. We intend to keep it there."

Slipper skippers

But is the view of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation the view of the whole industry? It is clearly the view of the bigger fishing interests, with the bigger boats and the bigger share of UK quota. They are the ones with most to gain from a cut in the activities of foreign boats in UK waters.

The pelagic fleet, for instance, mainly catches mackerel in very large boats. There are only 20 of operating out of Scottish ports.

That means they are only 1% of the whole fleet. Yet they land more than 40% of tonnage, with a value of nearly £200m last year.

That's more than white fish landings, including cod and haddock, and shellfish, which is mainly prawns. Most of that mackerel gets exported, because the British don't have much of a taste for it.

Thousands of boxes of fish in Peterhead

In the biggest boats, at more than 25m in length, a 2015 Scottish government survey found average pay was £116,000. Much of that is in crew share of landing value. So the Common Fisheries Policy may have cleared out many other boats and their crews. But it is working quite well for those that remain.

These boats have bought up quota and licences from other boats which then get scrapped. And we now have the so-called "slipper skippers", who stay at home and lease out quota to others.

Average pay in the fishing fleet in 2015 was £31,000. And in creel boats, fishing for lobster, it's a fifth of that, where it's often part-time work. It's a very varied industry.

Holistic mackerel

Who, then, speaks for the smaller scale part of the industry?

There is a creel-fishing group, which takes a strongly environmental approach to fishing effort that does least damage to the seabed.

And there was a breakaway from the SFF a year ago, by the Community Inshore Fisheries Alliance, or CIFA. It covers around 400 boats - a range of them fishing inshore, including some with quota, small trawlers, scallop dredgers, some creel boats and scallop divers.

They work out of ports in the Forth of Clyde, the Western Isles, Orkney, with smaller numbers in Galloway, Dunbar and Port Seaton in East Lothian and the East Neuk of Fife.

Elaine Whyte is with the Clyde Fishermen's Association and one of the main organisers of CIFA. She had been active within the committee structure of the SFF, but found claims by the smaller boat sector to gain more quota, or to channel resources into improved facilities such as ice plants on quaysides, were getting her members nowhere.

Elaine Whyte says it is important to make sure the voices of smaller boat fishermen are heard

Distribution of a member state's quota is not decided by the European Commission. It is down to governments. At Westminster and Holyrood, the choice has been not to allocate to smaller boats.

It has allowed the development of a market in quota, and skippers have been selling that quota to more efficient boats, including foreign companies which flag their boats under British or Scottish flags.

Ms Whyte said: "We came together through a real interest in trying to upgrade the infrastructure of the inshore fishermen, who are the guys you see at your pier, and to make sure they have a better say in how fisheries are managed in terms of quota.

"We were members of the SFF, and we left in November 2017 because we wanted to see these policies for inshore developed in a more holistic way."

She knows the SFF has been making the media running around Brexit, but says members of CIFA are not political and voted different ways in the 2016 referendum.

She added: "In terms of the dominant narrative that has been coming out, I would not blame the SFF for representing their members' interests. But we have different member interests. We represent the inshore men. So it's about making sure these other voices are coming through."

Flying fish

Some of those smaller boats' interests are more in keeping European markets open than in pushing foreign boats out of EU waters.

Some of its members land produce which is taken live to Barcelona within three days. They are acutely conscious of the importance of European markets, and of frictionless customs, without queues of trucks and their precious cargo dying from depleting oxygen in the water.

"Our market is about 86% in Spain, Italy and France," she says. "So that's really very important to us. We definitely want to keep that. Those markets took about 30 years to build up. It's not as simple as to say 'let's look internationally' (beyond Europe). We can't lose what we have".

The response to that, from Bertie Armstrong and the SFF, is that he represents 450 businesses, including some inshore boats, which work out of Mallaig, And he has a proposal he thinks will appeal to the smaller fleet, instead of sending shellfish to European markets by truck:

He said: "What about a refrigerated and frozen hub at Prestwick where we get this stuff all over the world? Over the last five years, the market has changed, and we send an awful lot to South Korea and to China. So the world is our new market".

It may yet happen. A small amount of premium salmon is already air freighted from sea loch to the best Chinese kitchens within three days.

But if that were the future for many more tonnes of produce, despite the expense (and carbon footprint) involved in flying fish and shellfish while on ice or in water, then the Flying Scottish Lobster might have taken off for Barcelona already.

And could that really sustain exports of hundreds of millions of tonnes of mackerel, haddock and cod?