Not normal times for situations vacant

- Published

Scotland has its lowest unemployment rate on record

Pay is responding to the tightness in the labour market

The economy will need better productivity and more workers but they are not being welcomed

Scotland can take its own route on productivity, so how will Derek Mackay use his budget plans to spark more life into the economy?

Brexit is bringing on record levels of business uncertainty, if we're to believe the Federation of Small Businesses in Scotland.

If there were an index for political perplexity, it would surely be hitting record highs too.

But amid the fog, the bit of the economy that keeps on surprising is in the employment data.

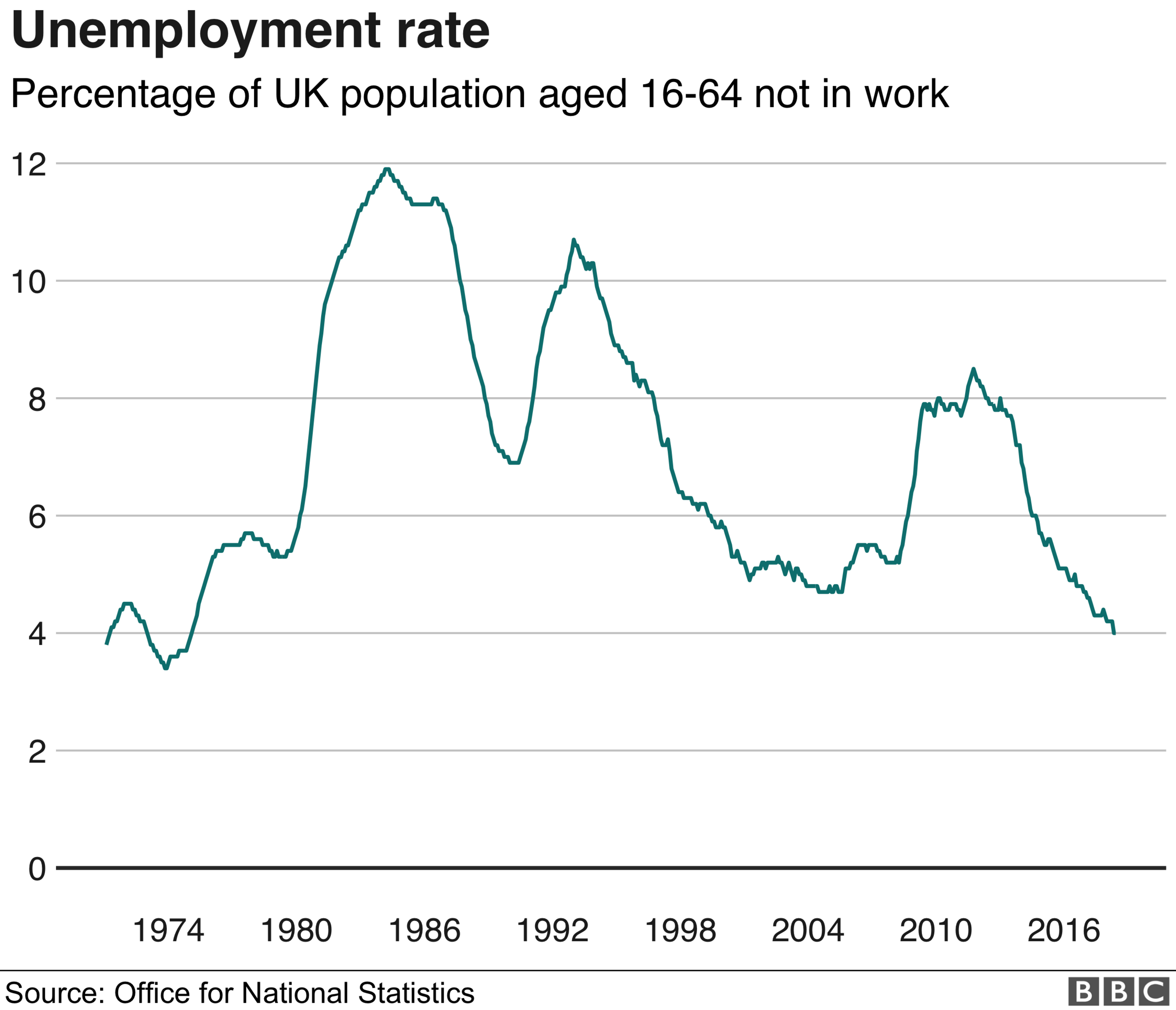

Scotland has hit a record low in unemployment, at 3.7%.

That's measured by the Labour Market Survey, which has been asking the question of a population sample since 1973: "Are you available for work and looking for work?"

Some 100,000 Scots answered 'yes' to that during August, September and October, down 13,000 on the preceding three months.

That's while the UK-wide figure was up 20,000 to a rate of 4.1%.

We've had exceptionally low rates for some time.

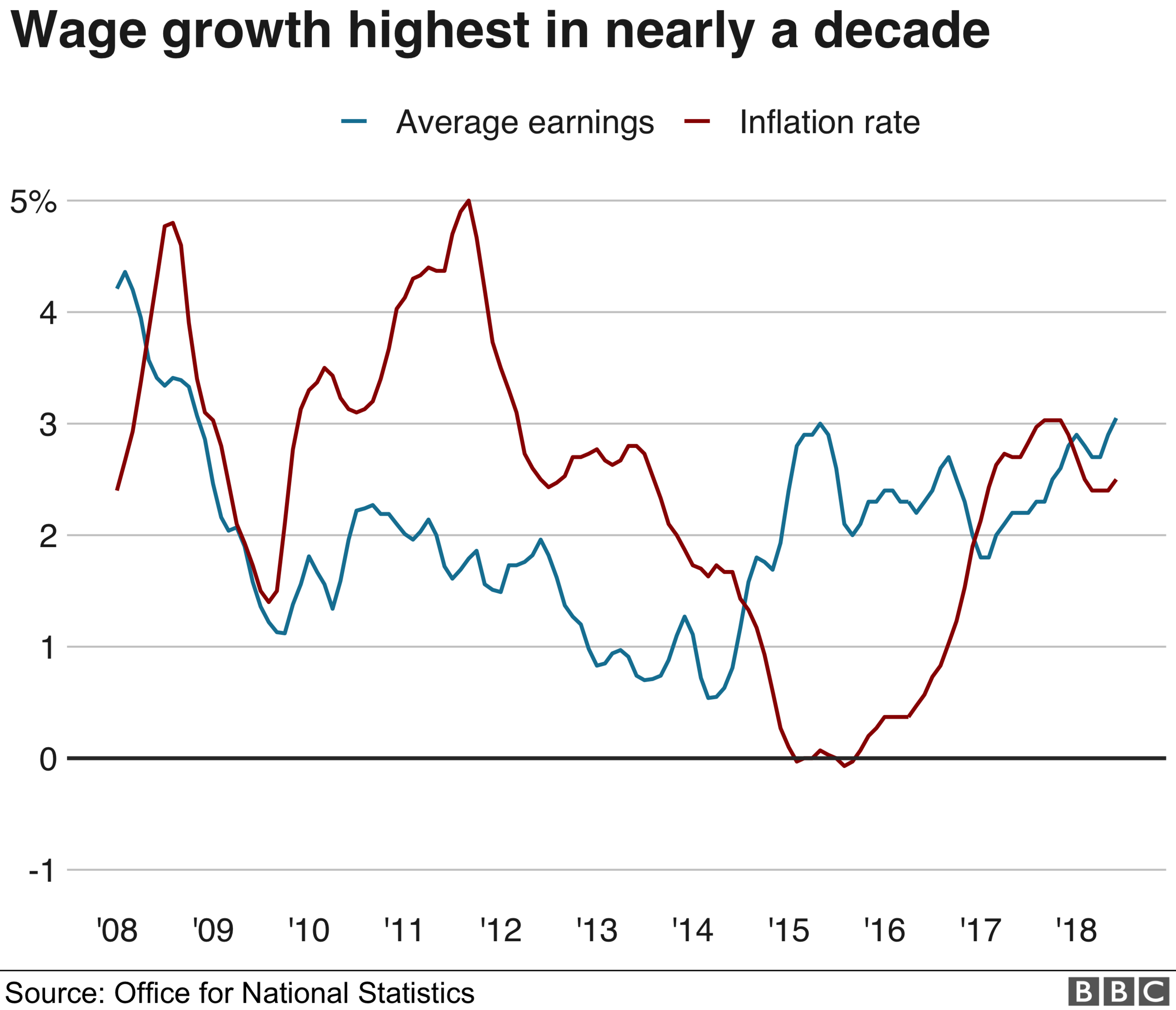

And one of the aspects of this that has puzzled economists has been the lack of wage inflation resulting from such a tight labour market.

There's been a lot of talk of skill shortages, and this month gives us another (near) record, in the number of vacancies counted by the Office for National Statistics: 848,000 across the UK.

This month's figures show the pressure is beginning to show - some might say, at last.

Price inflation

At 3.3% growth in weekly wages, a one percentage point gap has opened up between wage growth and price growth.

That is, British workers were, on average, earning 1% more in spending power than they did in October 2017.

In normal times, we'd be fretting about wage-led inflation taking off - employers have to pay more to recruit and retain workers, so they pass on that extra cost in prices, in turn bringing demands from workers to get paid more to keep up with those raised prices.

But these are not normal times. This is an inflation that makes things look more normal.

Also in normal times, a tight labour market like this would lead to increased demand for migrant workers. And in economic terms, that's what we've got.

More women are seeking work, while male unemployment has remained the same

But in Brexit Britain, migrant workers are leaving and not being replaced, because the political mood of the country has perhaps made them feel a tad unwelcome.

Also, the weakness of sterling has made this a less attractive country from which to remit earnings back home.

By the end of next week, we can expect Whitehall to publish its white paper on immigration - if Andrea Leadsom, Leader of the House of Commons, is to be believed (warning: not all ministerial plans seem to be working out.)

Hostile environment

That is where the Theresa May political project began. That is what has defined her.

The woman who famously chastised the Conservative Party for letting itself be portrayed as "the nasty party" went on to set a "hostile environment" within the Home Office immigration policy.

She stood firm in the face of pressure from Downing Street before she moved in - both David Cameron and George Osborne - telling her she should drop the overseas student element in net migration targets.

It was a sign that her negotiating style was one of simply digging her heels in, rather than trying to understand the other person's point of view. And that approach explains a lot about the Brexit mess she's in now.

The net immigration targets were missed by several miles, and the heightened tension around the issue was a major part of the 2016 referendum campaign.

Brexit could be said to have brought the targets within reach, by discouraging people from staying in Britain.

Holyrood budget

Yet this has happened at precisely the wrong moment in economic terms, when the labour market needs more workers.

At least one consequence ought to be improved training of UK nationals, to help plug those skills gaps.

Another will probably be a long-overdue improvement in productivity, partly driven by business investment in worker-replacing technology, such as robotics.

And talk of productivity brings us to the Holyrood budget.

Finance Secretary Derek Mackay will unveil his budget proposals for next year on Wednesday

Derek Mackay's draft plans are to be set out on Wednesday.

We know he has more money than he expected, following Phillip Hammond's October splurge, and that he's likely to plough most of of it into the NHS.

What we don't yet know is how far the finance secretary is going to continue divergence of Scotland's income tax from that of the rest of the UK.

Asked about it in an interview for The Times this week, he at least acknowledged that it has implications for Scottish growth.

If there's to be more divergence, politics tells us it will almost certainly be to skew/re-balance (choose your own verb, according to taste) the burden from lower to higher earners, and - he'll hope, though it doesn't necessarily follow - to raise more revenue in total.

The other factor we don't know is the growth path he's working with.

The Fraser of Allander economics institute on Tuesday published its quarterly growth forecast, unchanged at 1.4% to 1.5% over the next three years, with unemployment remaining around its low level now. That growth rate could be worse, but it's well below a healthy level.

Along with the draft budget, the Scottish Fiscal Commission will update its growth forecast.

It is the one with which Derek Mackay has to work in making his assumptions on tax revenue, and since last year - reflecting weak productivity figures - the SFC has been much more downbeat than others.

In their report, those Fraser of Allander economists have highlighted revised official figures showing the depth of the crash 10 years ago was significantly shallower in Scotland than previously thought, and not as deep as the UK as a whole.

It then shows that the long haul out of that recession has been more sluggish for Scotland than the UK over that decade.

The Institute is warning that a 'no-deal Brexit' could be twice as bad a hit as the not-so-bad figure we now have for the recession 10 years ago.

With unemployment so low, perhaps that holds less fear than it might do, in normal times. But to repeat, these are not normal times.

- Published16 October 2018