Brexit and the economy: the cost of kicking cans

- Published

Whatever else happened with Brexit, a weakened pound and the widespread message that Scotland remains open to Europe - whatever England's up to - should have kept tourism from the continent at a healthy high level.

But it's not looking that way.

Economic uncertainty - not just in Britain but around it - has seen a falling away in numbers, at least at the start of the year. It's obviously not the most important time of year for the industry, but it is increasingly a year-round line of work.

That finding was according to one of the surveys out recently, which was giving us an dashboard of updates on the strange economic goings-on in pre-Brexit Britain.

Sharp deterioration

The rest of the Scottish Chambers of Commerce quarterly survey was as you might expect, if you keep across the other headlines: a sharp deterioration in outlook, investment down in every sector other than construction, and orders down.

That was especially so for manufacturing - with the worst confidence levels since 2012 - and even more so for manufacturing exports.

The oil price has broached the $70 a barrel point once again

That reflects problems for the eurozone, which might also help explain the fall-off in visitor numbers. The slowdown across the region has been heading for recessionary territory, so overseas travel may be a discretionary spend people were choosing to do without.

The British economy, having moved from fastest-growing large economy to the slowest, now finds itself having company in the slow lane.

The other significant message from the Chambers of Commerce survey (like quite a few others, it was carried out by the Fraser of Allander Institute at Strathclyde University) is that cost pressures are on the rise.

National Living Wage

The oil price rise has broached the $70 point again, which ought to be good for much of the oil and gas sector, but puts cost into bits of the supply chain for manufacturing, retail and tourism.

And the payroll bill is on the rise. According to the Chambers of Commerce survey, that's most noticeable in retail and construction. (It doesn't cover every sector, but samples Representative ones.) Automatic enrolment for pensions has stepped up substantially this month.

There's the Apprenticeship Levy. And the so-called National Living Wage has seen an index-linked rise.

The change in costs that is most dynamic results from the shortage of available recruits. Average pay was up 3.6% on winter of 2017-18, with inflation pegged just below its 2% target.

In wage bargaining - if you can still call it that - trade unions and staff associations have the advantage.

And as some push for more or to catch up, it's causing for a more lively environment for industrial action in pursuit of pay, covering offshore workers and staff in airports, teachers and conventional manufacturing, such as Volvo heavy plant factory in Lanarkshire.

Sluggish

Despite all the uncertainty, last Tuesday, the Office for National Statistics published another month of frankly astonishing job figures.

The number of Scots seeking work in the winter months was down 8000, to only 93,000, taking the unemployment rate to only 3.3%.

To most economists, that is the kind of rate that counts as full employment, where the survey merely encounters the 'frictional' numbers, as people leave jobs and quickly take up new ones.

There's a regular caveat at this point about the quality of jobs to be had, how they are bunched towards the lower end of the pay distribution, with disappointingly slow progression, even for those taking on promoted roles in managing others.

Scotland's unemployment rate currently stands at 3.3%

That was borne out by figures from Eurostat, the official counters of European beans, showing the UK's payroll costs are only just above the EU average.

Of the older 15 members - not including the catch-up states of the former communist east - only Portugal, Spain and Greece have lower wage costs.

That makes for a dynamic economy, but it's also the low-wage economy that politicians told us they wanted to avoid - where low investment makes productivity exceptionally sluggish.

Diminishing spending power

And a reminder: even with full employment, it's only through rising productivity that we get collectively better off.

Without that, we're standing still while others scoot ahead, and over time, that is reflected with diminished spending power in international markets.

This is one explanation why the jobless numbers look so strong, against the backdrop of Brexit uncertainty.

Economic commentators this week seemed to agree that low investment means managers are choosing to spend their money on more people, and on retaining staff, rather than sink scarce resource into less flexible investment in equipment or training, through which productivity can be expected to improve.

Those familiar folk at Fraser of Allander put out their own periodical assessment of the economy, and pointed to the possibility that such a lack of investment could be backing up, in a potentially good way.

If government and MPs ever get to clarity on future trading relationships with the EU27 and beyond, then the pent-up desire to push ahead with company growth could lead to (slightly) elevated growth rates next year and the one after.

There was a hint of that also from the most recent Purchasing Managers survey.

Sighs and cries

From IHS Markit data firm, with Royal Bank of Scotland as sponsor, it was downbeat about recent output, but much more positive about the 12-month horizon.

But if not a managed Brexit, the Strathclyde economists were forecasting a disorderly 'no deal' departure would mean a drop in output of 5.5%, and a contracting economy in the next two years. The orderly variety would also mean contraction.

To business, there was a sigh of relief that Britain didn't topple out of the European Union this month, but also a cry of despair that the can is being kicked further down the road.

While MPs took the week off to recharge and regroup, business was totting up the cost of retaining its supply chain stockpiles, or to replenish those with a shelf-life. That carries cost, in stock and warehousing.

Graeme Roy, leading the institute at Strathclyde, and with a recent insider's knowledge of the economic team at St Andrew's House, offers the additional observation that while we've been obsessing with Brexit, or getting a budget passed for next year, there are other and longer-term challenges that are getting sidelined.

They include that sluggish productivity puzzle, and in public spending, the bits of the almost permanently-squeezed budget that don't get the political priority afforded to health or schools, which get further squeezed every year.

You can hear the creaking discomfort around the nation's council chambers on a near daily basis.

Ministerial headspace

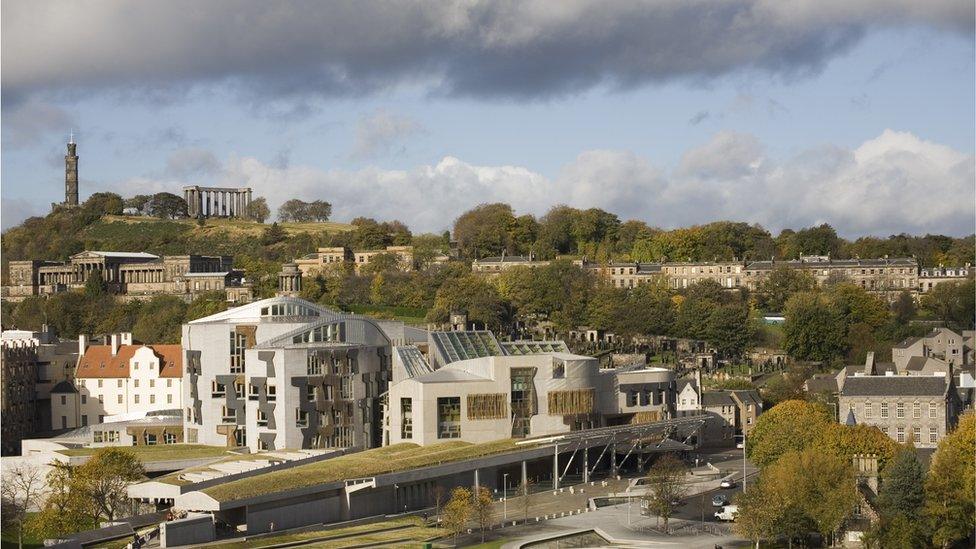

Twenty years after the first Scottish Parliament election, there's an Allander plea for a more strategic approach to the economic policies being pursued at Holyrood.

There's an obvious reason why the economic growth targets set in 2007 by the incoming SNP administration have not been met - things went somewhat awry on a global scale the following year.

But is there evidence of what works? The small business bonus scheme, for instance? It's popular with those who benefit, of course.

But it's expensive, in terms of tax revenue foregone. And for what benefit in alternative investment and company growth by recipients? We don't know.

Unintentional consequences? We don't know about them either, because the Scottish government has chosen not to find out.

At Holyrood, and even more obviously at Westminster, ministerial and civil service headspace seems to be entirely blocked out by constitutional issues - most immediately, Brexit planning and its potential widespread consequences. There's a price being paid in what's not being considered.

- Published11 April 2019