The next frontier of wind power

- Published

Beatrice is an offshore wind farm off Scotland's Caithness coast

Scotland is the world leader in floating offshore wind power, but that is unlikely to last, as the technology expands rapidly.

UK firms are lagging behind others in capturing the economic benefit of this technology, as it has with previous ones.

A new report starkly sets out the shortcomings of Britain's role in the supply chain, while other countries surge ahead. It recommends government action to back the industry, and to counteract the risks from Brexit.

Ever wondered at the strength of structure required to support a 200 metre-high offshore wind turbine when it is rotating at maximum throttle?

Onshore, it takes foundations of at least six metres of concrete to balance the forces on the tower from wind speed across the blades. Offshore, it requires heavy duty welding, and piles deep into the seabed.

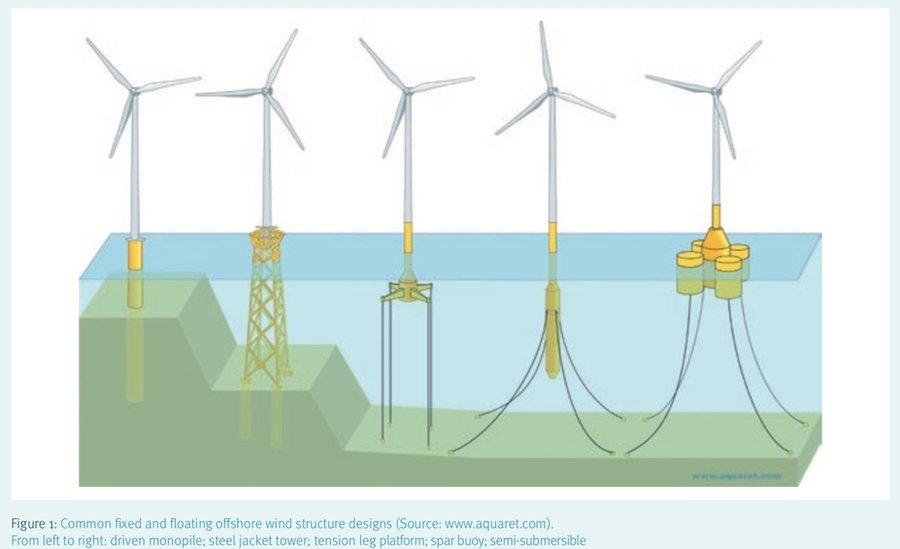

But what about a floating wind turbine? It is the next frontier for wind power. If it can be built at commercial scale, you can put a rotor wherever you can anchor it, and that's a lot more ocean than the 60 metre limit on conventional offshore platforms.

Currently, Scotland is the world leader in floating wind power, with 56% of all the world's capacity.

It has by far the biggest array, Buchan Deep, 25 km off the coast at Peterhead. That has five turbines rising 175m above the sea, and rated at 6 megawatts each.

Next in line is Kincardine, a site 15km to the south-east of Aberdeen, where you can currently see one floating turbine. Before long, that will be replaced by five turbines, at a construction cost of £325m. These will have monstrous big blades, each turbine rated at 9.5 megawatts.

They will be mounted on further semi-submersible floating rigs, which are set to replace the spar buoy means of balancing turbine forces (see illustration).

Built by Danish pioneer in wind turbine, Vestas, the blade design is so new that it isn't yet available, but should be from early next year. They will be sitting on Spanish-built semi-submersible floating legs.

The mooring chains will be Spanish, the anchors Dutch, the cabling Italian and project co-ordination and installation will be French.

Deep

The Buchan Deep project, known as Hywind, is Norwegian, is 75% owned by Equinor, formerly Statoil and majority owned by the Oslo government. Ten out of 36 companies in the supply chain are also based in Norway.

A Spanish firm made the floating foundations, at a shipyard owned by the government and where ships are built for the Armada, so its losses are covered by the Madrid government. Spanish firms also made the turbine towers and mooring lines, while the turbine blades are from German firm Siemens.

The latter, at least, has a large factory in Britain. But out of those 36 companies in the supply chain, only 13 were headquartered in the UK. At the Kincardine project, only eight out of 21 are British-based.

They are involved in important but less economically beneficial roles, such as surveying. At Buchan Deep, suction anchors came from Global Energy Group, based in Easter Ross and Aberdeen. Cabling was by Balfour Beatty and Subsea7, and installation cranes came from Granada Material Handling.

We know this from a report compiled by a team of technical and business academics, external at Strathclyde University, which sets out the lead Scotland has gained as a location for floating wind power, but the shortcomings of British industry in following through with the economic benefit.

It points out that the technology is set to be expanded to an enormous commercial scale during next decade. If all goes to plan around the world - a big 'if', though fixed platform offshore wind has grown at roughly this pace - there could be a rise from 57 installed megawatts last year to 4300 megawatts in 2030. If you add up all the projects that could be located in UK waters, that would reach 1900 megawatts.

In addition to Norway, Japan is pushing at the boundaries. So are US firms. France and Portugal are actively seeking a part in the race to grab a share of this technology.

And the UK? Well, it's pulling out of the European Union, which provides much of the research funding for the work done so far. This Strathclyde report recommends that either Britain stays in these networks or that Whitehall replaces that research funding.

UK energy policy is unhelpful in technologies which are still some way from being commercially proven. It is putting more of UK energy bill-payers' green subsidy into fixed platform offshore wind, as well as biomass, and leaving (mainland) onshore wind to the market, where it has now reached commercial costings.

So there's another recommendation in the report: to provide the subsidies and the industrial policy support that can build Britain's role in the supply chain for offshore floating wind.

It suggests the strategy could look to niche markets, for instance for supplying power to islands, and to offshore oil and gas platforms.

Brexit makes that more difficult, where companies are losing seamless access to EU markets they have built up. That threatens to weaken their profitability and their capacity for investing in new products and technologies.

"The overwhelming majority of these overseas firms (engaged in floating offshore wind) are either from the EU or the European Economic Area - and by extension the European single market," it says. "Brexit therefore raises serious questions about how leaving the single market and the customs union could impact negatively on the prospects of future UK floating wind projects.

"This is due to the potential introduction of tariffs, supply chain disruption and a lack of access to skilled labour. It also raises concerns about the health of the UK firms involved in floating wind, which currently export products or services to EU countries. A weakening of these firms may erode the UK's capacity to deliver its current pipeline of floating wind projects."

For now, UK government effort is going into resolving the potential disruption to existing markets. Its capacity for looking ahead to future markets, which are yet to develop fully, is another level of challenge.

The BiFab Methil yard in Fife

And the Scottish government has a role to play here too. It owns a stake in BiFab, the fabrication yards in Fife and Lewis, which have so far failed to attract much work from fixed platform or floating offshore wind.

They lack scale. And the UK Government's latest round of Contracts for Difference - the means of subsidy to offshore wind power - have shown how much costs are being driven down, making it harder for less efficient yards to compete for a share of work.

It has infuriated trade unions that British bill payers are forking out to subsidise green energy, but there have been so few requirements that economic benefit comes to British firms and workers.

Scottish ministers will soon own Ferguson shipyard in Inverclyde, which has potential to get involved in this supply chain as well.

There are opportunities there. Clearly, Norwegian state control of Equinor has not been a barrier to taking a world-leading role in investment. So what could that mean if applied to Methil, Burntisland, Arnish on Lewis, and Port Glasgow?

- Published10 March 2019