General election 2019: How Labour plans would affect Scotland

- Published

Much of Labour's radical reform agenda is to introduce policies for England already in place in Scotland

A big boost in funds would open up new options for Holyrood spending, so Scottish Labour has indicated some of its priorities for the 2021 campaign

Many tax hikes would apply north of the border, particularly affecting business. But on income tax, Holyrood could choose to undercut Westminster

Apart from facing resistance from vested interests, the big challenge of such a big and radical programme is whether the government machine could cope.

Labour's election manifesto is titled "Real Change". It's a description on which everyone can agree.

This is not the only set of options at this election to undermine the cynical non-voters' assertion that "they're all the same". If it were to implement its manifesto, a majority Labour government would make Britain look and feel very different.

There's quite a lot of detail there. Few pressure groups, other than business, fail to have their pet projects given a sentence or two.

You find, for instance, a commitment to "end nationality-based discrimination in seafarer pay" and "an advocate for human rights at every bilateral diplomatic meeting".

The most powerful pressure groups within Labour, the trade unions, can take credit for the most detailed set of proposals, changing the way the labour market works, and giving a boost to public sector pay. This is the union barons' agenda.

And amid the detail and analysis, you get some simple statements of breathtaking, radical ambition, and of potential cost and complexity:

"We will re-write the rules of the economy, and ensure everyone plays by them"

"Labour will scrap Universal Credit... and design an alternative system"

"We will put class at the heart of the equality agenda and create a new ground for discrimination on the grounds of socio-economic disadvantage"

Labour will "take back all PFI contracts"

All that while nationalising rail, mail, energy supply, English water companies and broadband; also setting up a public corporation to make generic medicines; oh yes, and sorting out Brexit.

What you don't sense, in reading this document, is that Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party is given to making difficult choices or setting priorities. The commitments just keeping coming. And there don't seem to be many trade-offs in this view of Britain's future.

Only a few objectives are given the more cautious language of aspiration, their achievement to be pushed off towards the end of the parliamentary term after next. Among them is the Universal Basic Income, which gets merely a pilot or two.

Bus pass

It's one of several parts of the manifesto where Labour thinking overlaps with the Scottish National Party and follows decisions of the Scottish Parliament going back 20 years. These include the "free" provision of long-term social care, prescription charges, dental checks, student tuition and hospital parking.

There's catch-up on childcare, and a desire to push the profit motive out of anything to do with the National Health Service.

With those in place already, the Scottish Labour Party has the space and a lot of moola to start developing ideas for the 2021 Holyrood election.

The Scottish version of the 2019 manifesto is a sort of work in progress. It has Labour's position at Holyrood inserted into it, much of it a critique of Scottish government policy as not going far enough.

On this basis, Richard Leonard would have £5bn of additional Holyrood block grant from a Labour Chancellor by 2023-24. That's the share of £84 billion of extra Treasury revenue (day-to-day) spending for that one year, in addition to big increases for pensions and benefits which would apply throughout the UK.

That sounds a lot, on a budget currently around £30bn. It's in addition to a £50 billion share of additional capital spend over 10 years, translating to a doubling of the current annual level.

Yet Labour has scaled back one of its eye-catching ambitions, of a bus pass for all, and not just those past 60. That's still an aspiration (now shared with Scottish Greens), but initially, Scottish Labour is committing to free buses for those aged up to 25 as well as 60-plus.

Scottish Labour leader Richard Leonard has signalled one use of the funds, if he wins in 2021, would be expansion of free school meals to all pupils, every day of the year. At present, they're provided on school days for primary one to three. (The costings, as reported here, look suspect - more than four times as many pupils, 80% more days, yet less than a doubling in budget?)

Back in 2007, Scottish Labour's manifesto for Holyrood came unstuck on the failure to agree an alternative to council tax. Alex Salmond and the SNP hounded them on "the hated council tax" with the pledge (since broken) to replace it with a local income tax.

Twelve years on, big change for council tax is merely a small part of Labour's revolution. The new way of raising funds for councils would be "a progressive alternative based on up-to-date valuations", while giving local authorities powers to raise money from "land value capture" (meaning, probably, that private landlords would be denied the windfall benefits from development).

The noisy election exchanges on Scotland's constitutional future are around the question of another independence referendum - Labour's leadership in London leaving the option open, though not "in the early years".

But buried amid those many manifesto promises are two significant developments for devolution of powers to Scotland: borrowing of funds, and workers' rights (the latter on condition that they are no weaker than the rest of the UK).

Borrowing risk

The issue of borrowing brings us to one of many big questions about Labour's programme for government: how can it be funded?

The answer has several elements: some ambitiously low costing, assuming that more public spending boosts growth and therefore revenue, a lot of borrowing, big changes to the way in which public accounts work, and a tax raid on higher earners, the wealthy and business.

The first magic trick is to push capital spending out of the fiscal targets. That is deemed to be investment, and therefore productive, so it seems we're not to treat it as actual money going out the door. The project goes further, by asserting that a pound invested in capital projects or nationalised companies is, or should be, a pound accrued to public assets.

The key measure thus becomes "public sector net worth". All of a sudden, a burgeoning national debt doesn't look so bad.

What matters is how the bond markets see this. What interests financiers is the extent of risk in buying bonds issued by the UK Government. It is already nearing £2 trillion of debt.

Under Labour's plans, there would be £84 billion per year of additional spending by 2023/24. If that is deemed to bring an uncomfortable risk of default, the credit rating gets a downgrade, and borrowing becomes tighter and more expensive.

Tax raid

International finance will also make a calculation on whether the UK, under Jeremy Corbyn, is a welcoming place for investment, and that's where this grand plan is setting off corporate alarm bells.

Why invest in UK utilities if they are about to be expropriated by Westminster?

How does Labour plan to claw back more than £11bn of earnings from offshore oil and gas, when some of America's oil majors have already sold up and left? (It doesn't say, but would consult.)

If employment rights are to be determined by trade unions, is the UK the country where multinational corporations will choose to locate job-creating plants?

And then there's tax. The corporation tax rate would soar, and not just through a rise in the headline rate from 19% to 26% of profits. There would also be the shutting down of business tax breaks. Tax advisers Blick Rothenberg reckon the effective rate looks more like 33%. That happens to be where the headline rate was in Margaret Thatcher's day. But globalised business has become more mobile since the 1980s, and responsive to competitive tax rates elsewhere.

High rollers

On personal taxation, the Institute of Fiscal Studies is sceptical about the claim that the figures can be made to add up by going after only the top 5% of earners. That's what Labour says it will do.

Changes to top rate tax throw down challenges and opportunities to Holyrood. Having powers over income tax, it could move from having higher tax rates for higher earners to having lower ones, potentially becoming a magnet for high rollers. Or it could match the rise, also in the expectation (though no certainty) that it would increase revenue.

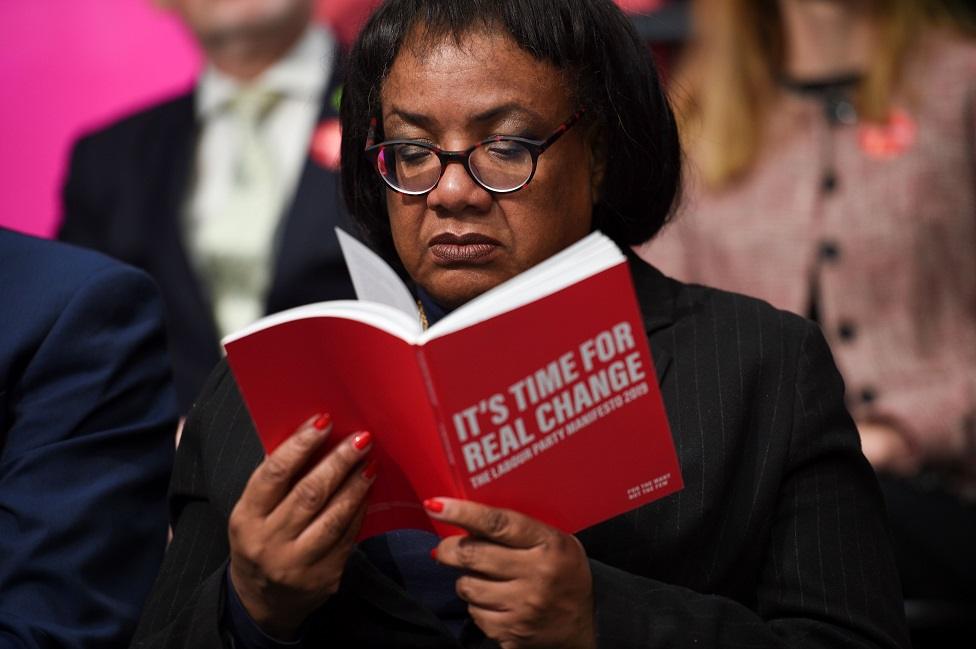

Dianne Abbot was at the launch of the Labour party manifesto in Birmingham

Among unintended consequences, Holyrood could gain from the closing of loopholes on wealthy Scots who derive income from capital gains and dividends in their companies.

At present, these are taxed at relatively low rates by Westminster. If they are re-classified as income, they would come within Holyrood's tax reach.

So while the spending side of Labour's manifesto leaves a lot for Holyrood to adapt, many tax implications reach across the border.

The windfall tax on oil and gas, to pay for the mass re-skilling of oil and gas workers, could be expected to have a disproportionate effect in Scotland.

The imposition of VAT on private school fees would apply in Scotland, with a working assumption that 5% of pupils would be priced out, and shift into state-funded schools.

Viewed overall, you can't criticise Labour for lacking ambition, even if you think they're the wrong ones.

Its manifesto opens up a big choice on the role and reach of the state, and therefore of the private sector.

Implementing it could be expected to meet dogged resistance from vested interests, starting with business.

But at least as big a challenge is that it includes so many moving parts. Labour intends to change Britain on numerous fronts simultaneously, when the machinery of government is already creaking and, particularly with Brexit, its capacity for change is severely stretched.

CONFUSED? Our simple election guide, external

POLICY GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

REGISTER: What you need to do to vote

- Published22 November 2019