Chancellor Rishi Sunak announces £330bn financial package

- Published

Chancellor Rishi Sunak told a press conference: "Never in peacetime have we faced an economic fight like this one."

£330bn seems a lot of money - so what does it mean, and how much time does it buy?

Scottish ministers have opted to use £2.2bn of crisis funding in similar ways to England.

The support is for business, and particularly helpful for small and medium-sized ones. Will it help big manufacturers, as car plants shut down, and what will it do for the most insecure and low-paid workers? That's yet to become clear.

There's a lot about the current crisis that challenges the wirings of the brain. For many of us, the scale of the global challenge and the changes to life, work and family just don't compute.

The £330bn, announced on Tuesday by the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, fits that same pattern of incomprehensibly big numbers. In the US, they're going for over a trillion dollars. That much moola surely ought to overwhelm a mere microbe?

So how to explain it, and the other measures set out by Rishi Sunak six days after his last big bazooka fell well short of meeting the challenge?

Well, it's not real money. It's a guarantee that stands behind real money. A bank may not wish to lend to your business if you are at heightened risk of default through the next few months. Or if it does, it'll price in a lot of risk.

But if the government is guaranteeing that money to the bank, then it's taking on the risk, and the cost of borrowing is closer to the very low rates of interest at which banks can access funds from the Bank of England.

As a result, we - the taxpayers - could be on the hook for a third of a trillion pounds, to add to the two trillion or so that now make up Britain's government debt. But to run up that extra debt would require all the lenders to collapse and all that debt to turn sour. And if things got all that bad, the economy would be in such dire straits anyway that we'd be contemplating government default.

On the rebound

The reckoning is that such money will provide a bridge from here to the point at which the restrictions on socialising and travel are withdrawn, and we come out of our Covid-19 hibernation spending with wild abandon - frolicking like cows being put out to spring pastures.

At that point, the businesses would still be there to ramp up operations and get back to business as usual. But they'd be carrying more debt, and this looks like it's based on a one-year loan, so it would have to be refinanced.

Will a year be enough? An alarming academic paper was published on Monday evening by public health statisticians in London, suggesting that the new strategy for suppressing coronavirus may get over a peak of activity this summer, but it may not be sorted out until a vaccination is available, and the best estimates for that are 18 months of frantic development and production.

Taking a loan to keep a cash-strapped business solvent until August or September is one thing if you can be confident of growth roaring back thereafter, but that may not be the case until well into next year.

Meanwhile, for airlines and perhaps airports, which are to have another support package worked out, there's the awkward question of how much capacity there should be. Should this be used as an opportunity to scale back the sector, as part of the drive to reduce climate-changing emissions?

Gig economy

The Rishi Mark 2 economic support package went back to the retail, leisure and hospitality sector, a day after it was torpedoed with the request that people should not go out to restaurants, bars and clubs.

There's a big wedge of money to give it a business rates holiday for a year - not just the smaller premises, but all of them.

That was announced for England, and matched by Fiona Hyslop, the Scottish economy secretary, when she announced how the £1.9bn of funding that comes to Holyrood from the chancellor's crisis splurge on Tuesday.

There will be a £10,000 grant for those businesses that fall beneath the threshold of the existing small business rates relief scheme. And for mid-sized businesses in those targeted sectors in shops, pubs, restaurants, clubs, hotels, etc, there will be a £25,000 grant.

That is real money. And those are real grants. Will they get anywhere close to persuading owners to shutter their businesses and lay off their staff?

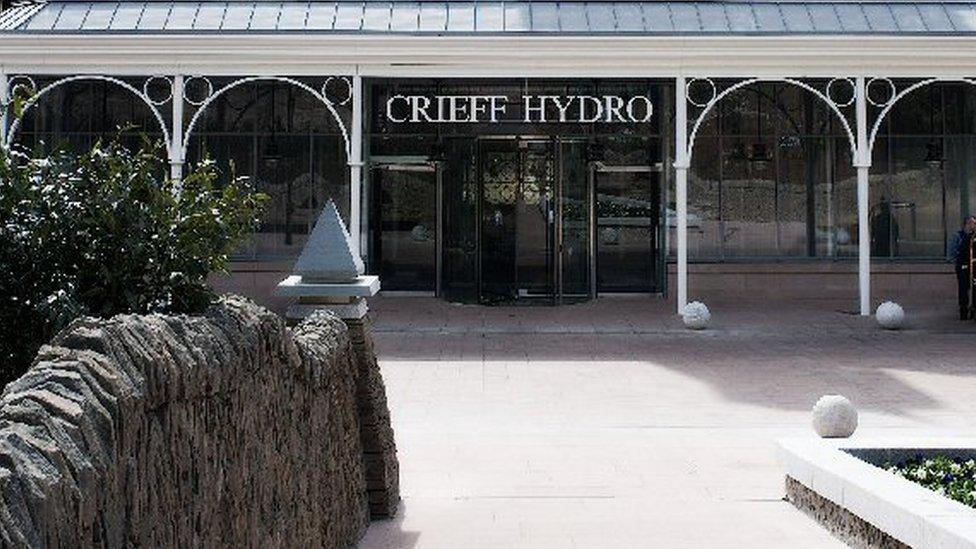

Crieff Hydro costs £60,000 a day in fixed costs, "just to open the doors"

The new governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, hopes so. He wants firms to think hard before they sack workers, to get in touch and see what is on offer.

But it's money splurged without any strings attached to employment, or incentives to retain workers. There is still a big gap where business says it needs big wage subsidies, of as much as 75%, as used in European countries. Payroll and other taxes could be delayed or abandoned for months or a year, starting with VAT this month.

Companies also want regulations relaxed. The Scottish Tourism Alliance, for instance, wants a temporary dropping of the requirement on tour operators to repatriate customers, as that could prove a big obstacle to getting foreign bookings restarted.

The speed of the response, and of getting those grants and loans into business bank accounts, is vital. Customers stayed away, because they were told to, restaurants are closing, staff are being laid off.

Earlier today, I was in a fishmonger who supplies high-end restaurants in Glasgow. With one such closure, he had 400 oysters and no market. I could have taken a pack in return for a charity donation - if only I liked oysters.

Stephen Leckie, of the Scottish Tourism Alliance, who runs the Crieff Hydro group of 11 hotels, gave an example of his financial challenge. Crieff Hydro costs £60,000 a day in fixed costs, "just to open the doors". Peebles Hydro is nearly £40,000 more. Some 46% of his costs are in pay.

Yet he says - and he was talking about the industry rather than his own business - hotels are going for a typical 80% occupancy in April and May to 30% or even 10%. This is the time of year when finance is running low and when bookings and trade should be picking up sharply. But instead of serving customers, office staff are busy taking cancellations. "That's catastrophic," Mr Leckie told John Beattie on Radio Scotland's Drivetime programme. "It's unheard of for one night, let alone a prolonged period."

There was a small part of Rishi Sunak's announcement addressed to helping individuals and families, with a mortgage holiday of three months. If you get on well with your bank, you might have got such a break from payments anyway.

And if you rent? An appeal by the Scottish government to landlords to go easy on arrears, while doubling the length of time - from three to six months - before arrears can lead to an eviction.

For the self-employed and gig economy workers, there was a promise of an employment support package. It's yet to be thrashed out. Unions and employers are working with government, and it's likely to require another humongously mind-boggling sum of money.

- Published17 March 2020

- Published17 March 2020

- Published16 March 2020