Economic cost of coronavirus lockdown keeps on rising

- Published

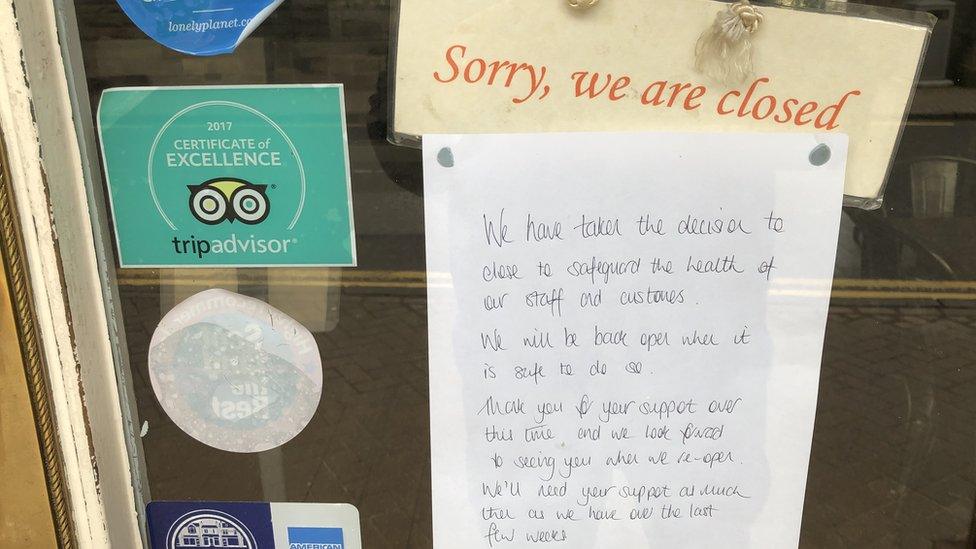

Many Scottish businesses have had to close their doors during lockdown

Holes are being plugged in business and job support schemes, but it's taking several efforts to get them right, and a long time for them to start paying out.

The scale of effort internationally is staggering - so far totalling $7.8 trillion - and as the lockdown continues and spreads the costs will rise further.

The easy thing to do might be a basic income for everyone. Abolish the starting rate for income tax, ensure everyone has a minimum, and work from there.

Easy in one sense, but in another sense, difficult to achieve without destroying work incentives. And very expensive.

The Reform Scotland think tank recently published, external a retread of an idea it backed some years back, gaining a nod of approval from the first minister. It's a bumper time to be thinking radically.

There has been a pilot running in Scotland, which was due to lead to a report by the end of March, but BBC Scotland now learns it's been delayed by more pressure concerns.

So until such a system can be figured out, ministers in Westminster and Holyrood are still trying to plug the gaps in the business and income support schemes of their own devising.

Scottish government changes to the Small Business Grant scheme were to plug a gaping hole where chains of outlets had been left a long way short of both what many need and what they'd get in England.

The changes were cautiously welcomed by business, as a sign at least that they've been listened to.

A full grant for the first property and 75% for each of the next ones could be a life-saver for chains of pubs, restaurants, grocers and bakers. That 75% is an improvement on zero.

But some won't be satisfied until it gets to the 100% grant for each property, as in England.

Others are waiting for the small print, or just waiting. The speed at which grants come through is putting strains on those without much cash in hand.

While that is costed at £120m, another £100m has been found in the magic money forest for those who have fallen through the cracks in other schemes.

At the front of that queue are people who are self-employed, but haven't been in that position long enough to have a track record of filing tax returns.

It should be a safety net for others who have felt left out: those who run businesses without any buildings - hence, no rateable value - such as those running marine tourism ventures, or those who operate out of something classified as a yard.

This is being disbursed through councils and enterprise agencies, and is sufficiently vague and free of conditions that it ought to avoid too many holes for future plugging.

The choice of the council channel could be a principled move to attune and adapt the scheme to local needs. It could be recognition that central government isn't geared up to run a small grants scheme.

It could also be cover for the Scottish government when people come calling, saying they haven't got the grant they think they need or deserve.

Kate Forbes - like all finance secretaries - has a tough job on her hands

What's worth noting here is that the finance secretary, Kate Forbes, said before Wednesday that choices had been made not to give anything to any properties in chains of outlets, beyond the first one.

Instead of England's system, she said she had opted to find special funds for aviation, seafood processing and sea fishing.

But it's a tough job being a finance minister these days, when the usual discipline of finite amounts of money keeps being undermined by more money being found.

She added a pleading note which is either naive or in tune with more altruistic times: please don't tap this fund if you don't really need it, as if companies seek funds the way shoppers seek out toilet roll.

That plea would work for individuals - I'm interested to find out how it works for companies.

Ms Forbes wants businesses to be as patient and thoughtful as individual shoppers

But it seems all fiscal discipline has gone, in this country and many others. The International Monetary Fund on Wednesday said direct fiscal costs have reached $3.3 trillion globally.

Public sector loans, including injections of equity into companies, are so far at $1.8 trillion.

Loan guarantees and other contingent liabilities, which is the biggest part of the UK approach, stretches to $2.7 trillion. Total: $7,800,000,000,000.

As the lockdown of much of the economy stretches into May, we're looking at an expensive extension of these UK and Scottish schemes, initially designed to end by the start of June.

Through these weeks, more and more companies are going to be reaching the end of their cash reserves.

Rishi Sunak has committed billions of pounds of business and employee support

Rishi Sunak has also been taking a walk in the magic money woods, with an extension of the Job Retention Scheme. That's the furloughing scheme, that puts employees on 80% of pay up to £2,500 per month.

That was due to include those on the payroll, and registered with HMRC, by 28 February.

But it left out those whose seasonal employment, such as those in tourism, were not employed so early in the year. The tourism sector said Is true of about one in 20 of its workers.

Back comes the Chancellor with bags more cash, to say that the cut-off deadline will be 19 March, the day before he announced the scheme. The Treasury calculates that should bring 200,000 people into the scheme.

This is his first effort to get the scheme right, each revision plugging holes. One of his concerns - and it's an understandable one - is to avoid fraud, and not to pay out for those who might try to jump on the furlough bandwagon after it set off.

However, even 19 March is unlikely to catch everyone in the Scottish tourism industry, for whom Easter is often the starting point for employment. Those people may be applying for those grants from their council or enterprise agency.

How many loans are actually getting through to businesses?

We've yet to see the Jobs Retention Scheme in action. Estimates of the demand for funds from it are far higher than the government first imagined. It should be possible to make claims from next week.

With the bureaucratic apparatus involved, set up at pace, what could possibly go wrong!?

What's clearly not going right is the effort to push loans out to businesses, which is the main plank of support to those above the rateable value threshold for grants.

Today, we got approval figures for loan applications, and it's not looking good.

Six thousand approvals, averaging £185,000. The British Council of Chambers reckon only 2% of firms have been successful in getting backing from the government loan schemes.

In those circumstances, it doesn't much matter that it's worth up to £330 billion.

The obstacles are many. One condition of the government-backed loans is that the Treasury will only back 80%. The other 20% is to ensure banks aren't too reckless.

Yet they seem to be behaving as if they were on the hook for all that money. The paperwork continues to take a lot of time. Banks continue to score applications with a heavy pen.

The support for jobs and small business may be getting there at last. But sustaining the finances of middle-sized companies, by relying on loans, is a bigger challenge to sustain employment in the medium to long term.