Just when you thought it safe to go back in the water

- Published

Time for an update on Brexit, which hasn't gone away, and nor have the UK or EU edged any closer to a deal on their future relationship.

Boris Johnson goes into a summit this month, where he decides whether to keep trying for an agreement, or walk away and pay the high economic cost of 'no deal'.

Fisheries has become a totemic and a real obstacle to a deal, where compromise looks particularly difficult, and here's why.

Much of Britain seems to have gone to the beach. In hot weather, why not take a cooling dip in the sea, and leave lockdown constraints on the beach with your towel? But apart from the crowds and infection risk, beware of the political and economic undercurrents.

Brexit is about to surface once more - a giant creature that's been lurking in the shallows while attention has been turned elsewhere. With each round of inconclusive talks, it is those waters, and specifically the fish and shellfish in them, that become more central to the outcome.

It features a trial of negotiating strength, guile and apparently quite a lot of self-delusion. A great deal more depends on the outcome than the fishery jobs.

Yes, it's four months since the UK left the European Union, and seven months until the transition is scheduled to end. This week is an important one for deciding the terms of the new relationship, and the early signs are that it's going badly.

So it's time for an update, with a reminder of what was going on last time you paid any attention.

Aussie-style

At the end of January, Boris Johnson was busy booking his place in history, or so he thought. What he was doing rather less was heeding the warning klaxons about an infection spreading rapidly in China. It's the latter that seems more likely to define his term as prime minister.

However, the way things are looking, we could be heading not only for the biggest recession at least since the 1930s, thanks to Covid-19, but also that Brexit cliff-edge we were talking about last year.

There's no sign of entente breaking out via the Microsoft Teams meetings that have had to become the diplomatic channels for UK and EU negotiating teams.

The fishing industry has become a special focus for Brexiteers

Supporters of Brexit are determined there will not be a delay on the 31 December end to transition. That remains, firmly, the government's position.

It can't simply play for time, and kick the can down Theresa May Boulevard, because the transition deal states that any delay has to be for at least two years. To Brexiteer Tory MPs, that's an impossibly high price for accepting an extension.

Later this month, in a summit meeting, the two sides are scheduled to reflect on their negotiations and make a judgement as to whether it is worth continuing the effort to get a deal.

And if they conclude there is not, those Brexiteers say: so be it - the UK would be trading with the European Union on what we have learned to call World Trade Organisation (WTO) terms. Mr Johnson calls them Australia-style terms. Either way, they are the WTO's least effective arrangements to ease trading.

'Johnny Foreigner'

For now, there are two broad schools of thinking on this. One embraces a future where Britain can shed Europe's environmental, social and labour rules, and become more competitive than the European Union. For them, sovereignty is all and compromise is for Johnny Foreigner.

The other is aghast - looking at the unprecedented calamity that has struck the British, European and global economies due to Covid-19, and wondering how anyone could consider this a good time to take a risk on a full break from Europe's single market and customs union.

Brexiteer outrider commentators are arguing that the Brexit pain won't feel so bad in the context of suffering something much worse.

But from the academic network known as UK in a Changing Europe, there's been a reminder that their modelling suggests an economy that will grow 8.1% less in the next 10 years than it might otherwise be expected to do, while UK government modelling suggests a 7.6% shortfall.

Boris Johnson's legacy as PM may end up being defined by coronavirus rather than Brexit

(We're very unlikely to be able to measure the true impact of Brexit, because there will be other, very powerful factors at work in trying to repair the economy post-pandemic. The closest we're likely to get is by comparison with similar countries still inside the EU.)

'Dispensable'

In this crunch week of talks, the negotiating gulf is around promises which the EU members thought they had secured in tying Britain to Europe's "level playing field" of common standards on environment, social and labour market standards.

There is a big gap also on their expectation of how disputes over such standards will be resolved. The EU wants that in its Court of Justice. The UK says "no way, Jose".

And then there's fish. How is it that fisheries have become the third track of disagreement and impasse? And why, when one considers the industry is tiny, relative to the British economy (0.1% of economic output) and population, and it's tinier by EU ones?

One part of the answer is that fishing occupies a totemic and political role more than an economically significant one. This was the British industry that was hit hardest by entry into the European Common Market. Whitehall in the 1970s saw it as "dispensable", or so it was admitted in an internal memo.

Everything since then - including increased efficiency of catch forcing a reduction in the number of boats and men, and the harsh counter-measures to over-fishing - has been implemented through European institutions, so it's been blamed on Brussels. It has come, therefore, to be a special focus for Brexiteers.

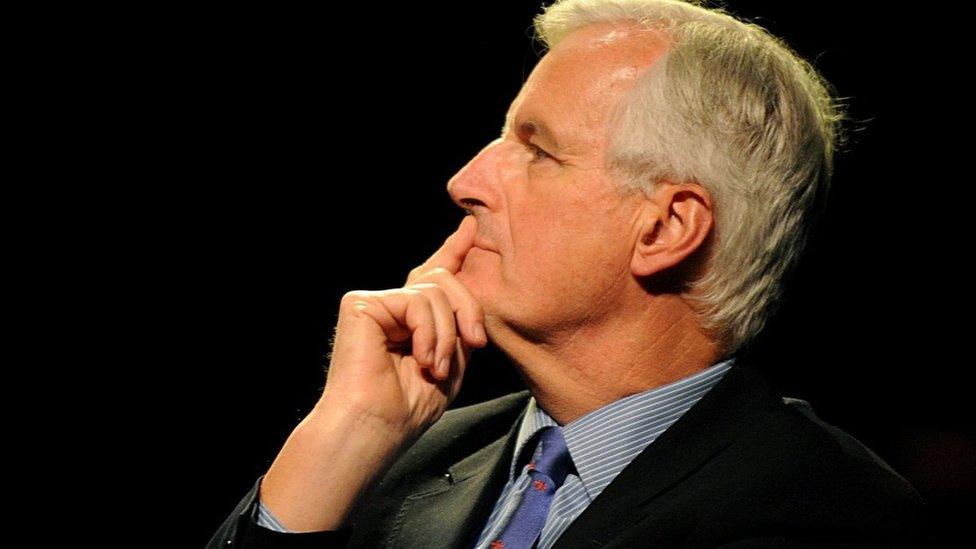

Michel Barnier, the The EU's chief Brexit negotiator, has no intention of trading away fishing rights

With well over half the tonnage of fish caught in UK waters landed by foreign-registered boats - roughly eight times the amount caught by British boats in EU countries' waters - it has also become commercially important to the fishing fleets of the UK's nearest neighbours.

Quid pro quo

The EU negotiating mandate wants to retain what it calls "relative stability", which is an allocation of quota based on the shares back in the 1970s. If anyone thinks European capitals are ready to go soft on Michel Barnier's mandate, they should be aware that he was told to strengthen the mandate - that is, not to trade away those fishing rights.

Look at it from President Emmanuel Macron's point of view: his re-election efforts will not be helped if there's uproar and port blockades in the politically-significant Pas de Calais region. We recently got a taste of what is a serious risk, with a skirmish between boats fishing around the Channel Islands.

The British want annual negotiations, based on sustainable quotas. In the jargon, at which fishery management excels, it's called "zonal attachment". This assumes that the British government will have control over UK waters, so its fleet will get a much bigger share.

This is important to the UK negotiating position, which is the other reason fishing is disproportionately important to these talks. This is one industry on which the UK has leverage. It has a lot to gain from ending CFP quotas, and a lot it could give.

But it needs to avoid quid pro quo deals in which fish are traded with access to European markets where the UK badly needs concessions from Brussels, such as the finance sector's reach into European markets.

Parking the sharing of fish quotas, by saying they'll be decided each year on the evidence available, and that Britain can relate to the CFP in the same way as Norway, would avoid the pressure to give ground on quota specifics as part of an over-arching deal.

The EU is firmly saying that the whole deal has to be integrated, without such side deals. It also has some leverage on fisheries, in that Britain sells a lot of fish into the European market, and there are more jobs in processing than in fishing.

Not all fishing businesses or communities are as gung-ho for Brexit as in north-east Scotland or Cornwall. Neither Hebridean creelmen nor Grimsby gutters want the disadvantage of tariffs being levied on those export sales, or of delays at the Channel for delivery of fresh produce.

Capitulation

How will this work out? With difficulty. Negotiations often involve bluster, claiming to be digging in to "red line" negotiating positions and timetables. The British side has been big on that approach since the 2016 referendum, allied to a consistent misreading of where negotiating power lies. It hasn't worked well so far, instead leading to a series of embarrassing capitulations. But this week, it's still the tactic being used.

This month, Boris Johnson will have to choose whether he continues the talks or plays to hardliners in his party who prefer "no deal" to compromise.

Through his handling of lockdown and the Cummings affair, the prime minister has weakened his position within Tory ranks. Facing him in the Commons, he now has a Labour opponent, in Sir Keir Starmer, who can hound him over the choice he makes.

The current impasse may turn out to be bluff. There's no point in hinting at an extension until the point when you have to propose one. Compromises, when they eventually come, tend to be made quickly.

But surprises aren't always welcome. For both sides, there is the need to get the deal through the European Parliament and 28 national parliaments. Westminster is one.

Another parliament, without a veto, is at Holyrood. It will have a say, however, and a noisy one, in the months leading up to the next election.

In Scotland, Brexit is a faultline that currently looks likely to suit the SNP better than Jackson Carlaw's Tories.