Recession rollercoaster: Biggest slump on record for UK

- Published

What is a recession?

We now have numbers with which to measure the recession we could sense months ago.

The data suggests the UK recession has gone deeper than others, and it has touched forgotten parts of the economy.

It also sets the scale of the challenge for governments, to continue or withdraw support measures and to be clear about priorities.

Who'd huv thunk it? A recession, you say?

Yes, two consecutive quarters of declining output, according to the Office for National Statistics, confirms what we all knew.

That's not to disparage the statisticians. This is such an exceptional recession that it needs to be enumerated carefully.

The underlying numbers reminded us of some aspects of recession that can get overlooked. They showed, or claimed to show, how much "output" from the health and social care sector dropped during April, May and June.

While some parts of hospitals, some medical teams and care home staff were working flat out, the system as a whole saw a 27% drop in activity.

Education saw a 34% fall in "output"

In education, there was a 34% fall in "output". Don't ask me how you measure output from education, and remember that the informal, uncounted education sector, at the nation's kitchen tables, was picking up where the formal, salaried teaching force were told to stay at home.

The water supply and sewerage don't get much attention during a recession, but one measure of the downturn in economic activity was the 6% decrease in output from that sector.

Similarly, with much of industry switched off and lots of home entertainment appliances switched on, the balance saw a 9% drop in electricity and gas output. That latter number may be affected also by unusually warm weather.

Uptick in June

With an upswing in activity of nearly 9% in June - another exceptional figure - as businesses re-opened, it's clear that the recession is not likely to extend to a third quarter. That's unless there's a renewed lockdown.

But even strong growth is no guarantee of returning to anything like normal by the end of the year.

And this moment to reflect on where we've been over the past six months is also a chance to look ahead.

As with any recession, you tend to have it confirmed after the worst of it is over. And it's also expected that company collapses and job losses are likely to follow after the upswing has begun.

That delayed effect will be all the more pronounced because of the support measures by business to keep employing companies solvent and to take payroll costs off their hands. As that support is withdrawn, expect the job losses to mount up.

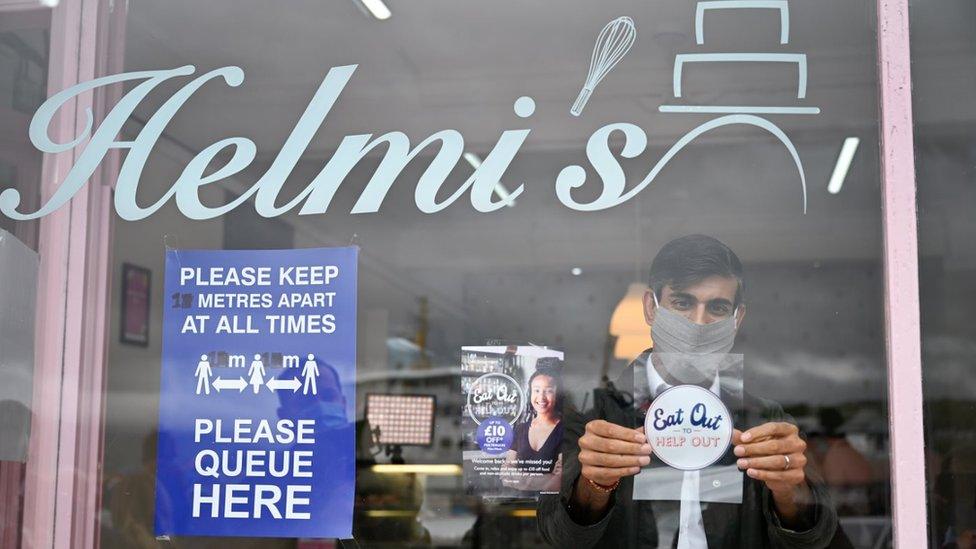

There have been calls to extend support to hard-hit sectors including hospitality

There's pressure on Rishi Sunak to extend furlough, at least for some sectors that cannot possibly get back to normality because of the constraints placed on them. Events and live entertainment is an obvious concern.

He says the economy and businesses need to stop relying on it, after 1.2m employers put 9.6m people on furlough, at a cost of £33.8bn.

There is also pressure to extend business rates holidays, and to dig deep into borrowing once more to provide loans to businesses. The Bounce Back Loan is worth up to £50,000 to smaller companies, with 100% government guarantee behind it, very few questions asked.

By this week, it had been secured by 1.16m firms, with loans worth £35bn.

CBILS, or coronavirus business interruption loans, have been worth £16.8bn to 60,000 companies, with an 80% government-backed guarantee.

Priorities and pace

The ONS numbers make it clear - and uncomfortably so, for the UK government - that the recession has been deeper than comparable large economies, other than Spain.

The USA has seen a lower dip than the UK in the first half of the year, but its infection controls have made a bad start to the second half, so it might get a lot worse before it gets better.

Britain was later into lockdown and stayed there longer. Its recovery path for the second half of the year owes a lot to decisions made by Rishi Sunak and fellow ministers.

But there's a warning out there also to the Scottish government, and it comes from the man chosen to lead its team of advisers on economic recovery.

Benny Higgins has been on the BBC Radio Scotland airwaves and writing for The Scotsman, external, voicing his concern about the "dilatory" nature of response to some of the recommendations.

One he cites is in "convening power" of ministers to get banks round the table and pushing them into taking more responsibility for their customers' financial health.

"The real test will be the prioritisation and focus of activity, and the pace of execution," he writes.

To make priorities is to de-prioritise those that aren't on the list. That's tricky, and political.

As Mr Higgins points out, the Scottish government has set itself the hard task of recovering economic growth while shifting to a different target of improved "wellbeing".