Brexit: The reality dawns

- Published

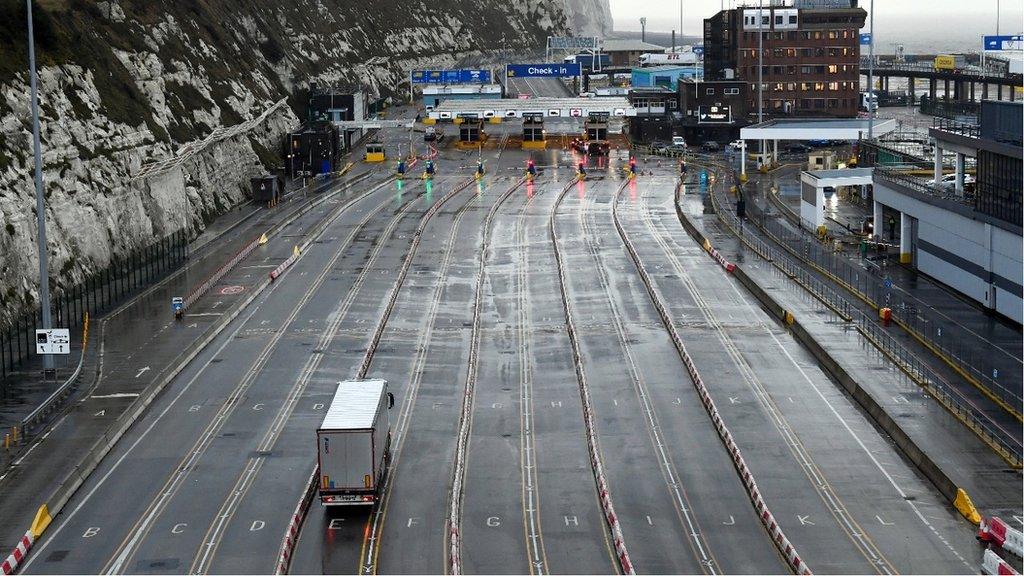

Lorry drivers' documentation is checked by police officers at the Port of Dover

While attention has been on infection control and the Channel, it's Northern Ireland which is perhaps the most astonishing and far-reaching aspect of Brexit. So far. Its treatment suggests that it is now English nationalism that will determine whether the UK remains united.

Scottish fish exports have become the first to run into problems with paperwork required before trucks leave the country, as well as when they reach France. They're being joined by others.

The first eight days have had some allowance for change, but the "period of grace" is ending, and from hauliers to ferry firms and British suppliers of imported goods to the EU, firms are finding the new trading reality is complex and costly.

The real Brexit - the economic one - arrived alongside a sudden surge in the health crisis. There was relief that "no deal" was avoided, so while being told to stay at home, the nation's attention was, understandably, not on the seismic change that just took place in Britain's place in the world.

A week on, it may seem that the rupture with the European Union's single market and customs union has passed without casualty, while paling into insignificance beside the surge of hospitalisations and deaths, and renewed extraordinary restrictions on individual liberty.

These seem more immediate pressures than the split of Northern Ireland's economy from that of mainland Britain. But in the longer term, we'll surely find time and space to reflect on the extraordinary outcome of the long road to Brexit - that somehow took the UK's marketplace from the world's biggest to one that is smaller than the UK itself.

Perhaps it will be if or when the economic split leads towards a political one. Having played a key role in bringing about Brexit, the unionists of Ulster may find their cause fatally undermined by it.

For those who see the future of the United Kingdom through a Scottish prism, it's easy to miss the growing possibility that a uniting Ireland could pull away from the UK before Scots decide to do so.

And there may not be much resistance. The Conservatives who argued most strongly for Brexit are now less concerned about keeping the UK market united. Their bluff called, the threat to break the 2019 Northern Ireland Protocol withdrawn, the economic border is now in the North Channel. So now, they resort to pretending that it hasn't happened.

How much faster might they ditch their enthusiasm for Scotland's place in the union? The unity of the Kingdom now looks more vulnerable to the choices made by English nationalists than those of the other three parts.

Grace no more

One reason you couldn't feel the tremors from that constitutional seismic activity was that a lot of cross border traffic wasn't moving. Many exporters of goods were holding back, having stocked up across the boundaries, when they didn't know if there would be tariffs or a deal. With stock in place, they could afford to wait and see.

But with fish, not so much. It was one of the big issues through the talks, beyond its relative importance to EU or UK economies. And because it has to be delivered super-fresh, it was the first sector to feel the frost of bureaucracy descend.

Within three days of normal service resuming, dozens of trucks were stuck in France. Calais wasn't ready to receive inbound fish, so drivers had to divert to the slower ferry option to Dunkirk.

From there, they need permission to go on to Boulogne-sur-Mer, where the border post is. It's also the marketplace for around 80% of UK fish produce exported into the EU. But there were glitches in French computer software.

So far, there has been a "period of grace". But come Friday night, exporters are braced for things to get much tougher. French customs officials can make it as tough as they want, with slow inspections, while taking a forensic approach to the paperwork.

So back in Lanarkshire, at the three depots where Scottish food exports have been put into giant chiller halls, and then loaded up for one-day delivery to Boulogne, they're keen to make sure that the paperwork is correct.

Some sectors are used to this, if they send high value salmon and shellfish outside the EU, often air-freighting it. As a result, a truckload of salmon from one producer is relatively simple, and they are getting despatched much faster than others. The Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation say members send 100 tonnes of salmon into France every day in a more normal January, worth £23m over the month.

However, most exporters are new to the bureaucracy of selling into the EU from outside. And it seems too many were not ready for what they faced. The complexity is worst for lorries carrying fish for several different exporters, each of which has paperwork to be processed. They tend to move at the speed of the least well prepared.

"More wrong than right"

Eleven vets are working across the three hubs, with 50 more available to shift from their animal welfare duties at abattoirs. They've been put there by the Food Standards Scotland agency, on instructions from the Scottish government, to avoid dependence on private vets and councils' environmental health officers already overstretched with Covid compliance. While vets are required to certificate meat products going into the EU market, vets or environmental health officers can do so for fish.

The inspectors in Lanarkshire carry their own personal stamp when they sign off these six-page, densely-worded Export Health Certificates. They carry professional liability if they don't do their job properly. And a lot can go wrong with a consignment of seafood, so that's a real risk.

Earlier this week, two trucks took more than five hours to be processed and leave Lanarkshire, when the intention was to have them turned around in as little as 45 minutes, and no more than two hours. One truck took eight hours.

Those on the ground report that the consignment paperwork didn't tally with the goods being loaded. Some paperwork was presented for Northern Ireland but was for goods going to France.

Businesses were warned, observes one of those involved: "You can lead a horse to water..." But if firms thought the Brexit prospect would melt away, as it had twice before, then they were not ready for all the certification; the coding for tax, for health, for the safety inspection by local authorities of the fishing vessel or processing plant, checks of the packaging integrity.

"There's more wrong with their paperwork than there is right," I've been told. The feedback from France is that as much as 90% of the UK inbound paperwork is incorrect.

Only three days in, DFDS, at its logistics hub in Larkhall, was telling clients that a guaranteed one-day service was immediately shifting to three days at best. The difference translates into reduced value to that fish when it arrives at Boulogne-sur-Mer.

The Scottish Seafood Association was sending a message to skippers at sea that they may find quayside prices depressed when they return to port.

Garment trade

Scottish fish were among the first to face the impact of Brexit, but they weren't alone. Supermarket shelves in Northern Ireland have been emptying, either through a rush to secure food, or because businesses simply aren't able to send fresh food as before. Some trucks were delayed as they arrived in Northern Ireland, because the paperwork wasn't right.

There are empty shelves in some supermarkets in Northern Ireland

Wales is a major route for trucks taking goods into the Irish Republic. One logistics firm, Gwynedd Shipping, had a backlog of 60 trucks by Thursday, unable to generate the computer codes necessary to board ferries for Dublin. The queues may not be obvious, because the trucks are waiting at depots all over the country.

It was only this week that some major UK clothing retailers found that they face double tariffs if they import clothes, for instance, from outside the European Union, and then export them to Ireland and other EU nations.

It makes no sense to pay a 12% tariff on a finished garment, and then pay it again to send it to a shop in Dublin. A shirt from Bangladesh or Cambodia enters the UK tariff free, but a 12% tariff is applied at the EU boundary.

The lesson is clear: cut out the British element, and for goods destined for the EU, bypass the UK, along with any jobs involved.

Red tape

DPD joined in the confusion. The logistics and delivery firm found sending goods from the UK into EU is much more complex than the planning had projected. By Thursday night, it was suspending all such parcel traffic, to review how best to handle the added hassle, delay and cost.

Meanwhile, Stena was warning commercial clients that from Friday morning they'll need a GMR (goods movement reference) number, as well as a PBN (pre-boarding notification). To give you a flavour of it, here's a small part of the advice from Ireland's revenue service, and it seems this even applies to freight moving between Scotland and Northern Ireland:

"All safety and security, customs declarations and transit declarations must be lodged prior to arrival at the ferry port of departure in the third country. Additionally, the Movement Reference Number (MRN) of the aforementioned declarations for all goods carried on a vehicle or trailer, must be included in a Pre-Boarding Notification to be submitted to Revenue prior to the arrival of the goods at the ferry port of departure in the third country.

"Failure to comply with this requirement is an offence, punishable on summary conviction of a fine of €5,000 or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months or both."

And all this applies even to empty trailers. You'll probably recall that Brexit was intended to remove the risk of strangulation by Brussels red tape.

Barriers

Even when everyone knows what paperwork is required, and when it is being processed smoothly, it still carries cost. In the Scottish fish exporting trade, for just one example, 150,000 certificates will probably be needed annually.

Says Donna Fordyce, chief executive of Seafood Scotland: "The problem is no longer hypothetical. It is happening right now. We are doing all we can to help companies get the paperwork done. It will take time to fix - which we know many seafood companies can't afford right now.

"The last 24 hours has really delivered what was expected - new bureaucratic non-tariff barriers and no one body with the tools to be able to fix the situation" - least of all a prime minister who observed last week that the trade deal has left "no non-tariff barriers to trade".

Related topics

- Published8 January 2021

- Published8 January 2021

- Published6 January 2021