Trading relationships three months after Brexit

- Published

Three months on, new trading relationships are being sought, but the disruption to European trade has been significant.

Starting with fish, it extends across the food sector, and a different set of problems beset Scottish engineering firms.

Smaller companies face the biggest problems with multiple consignments in one truck. And without guaranteed delivery, customer sentiment is shifting, to find more reliable trading partners.

Duncan Ross is a specialist at growing biodynamic and organic herbs in a walled garden on the Black Isle, overlooking the Cromarty Firth.

In the pure Highland air, he could get premium prices in Germany for plants such as arnica. But even before he encountered the paperwork for consignments being sent to the European Union, he stopped the trade - cutting off around a fifth of his business.

For a small business, the certification each time a consignment was required wasn't worth his time.

So he didn't have to encounter another obstacle to sending plants - that every product with Great British soil attached to it is simply banned from entering the EU. It was trusted as safe in December, but no longer.

At Glendoick nursery near Perth, Ken Cox supplies planted flowers such as rhododendrons to a gold-plated customer base of display gardens. He says he has lost 30% of sales that used to go to the rest of the EU. Without it, he told BBC Scotland: "I don't think it's going to be sustainable.

"We've been sending plants to Europe for 30 years. If there are bugs in the soil, they'll have got them a long time ago, so this is really just a bureaucratic thing."

Ken Cox's nursery in Perthshire has lost 30% of sales that used to go to the rest of the EU

Those rules should apply to Northern Ireland too; nothing with earth attached, no live sheep, no seed potatoes and no minced meat. However, the anomalies at the Cairnryan to Larne and Belfast crossing are among those rules to which the British government signed up but is now refusing to implement.

The grace period for introducing customs checks in the province has been unilaterally extended by Whitehall. The EU is crying foul, and suing under the terms of the Christmas Eve deal. With chief negotiator Lord David Frost now installed as Brexit minister, and telling Brussels to get over its resentment of Brexit, abrasive relations have been getting rawer.

'Global Britain'

Three months since Britain left the single market and customs union, and Brexit continues to be a headache for exporters and some importers. On the upside, there are no backlogged queues at ferry ports in Kent. Vast car parks prepared for slowed customs processes have been stood down.

Some international companies are choosing to locate bases in Britain, where they previously operated from the EU. Investment in British technology and science is looking healthy, helped by the success of its pharma sector in developing a Covid vaccine.

There are other signs of progress, with the UK government making moves towards trade talks in the Pacific. The new Biden administration in Washington sounds more positive about a deal than some in Britain had feared. One legacy trans-Atlantic trade battle over airliners has been paused by the US, EU and UK, giving space to get it resolved.

But as the senior UK minister Michael Gove was told in a recent meeting with Scottish engineering firms, "it's much easier to sell to an existing European customer than to find a new one elsewhere".

The Brexiteer dream of a shift beyond Europe to "global Britain" is ringing hollow for those who find it more difficult to sell to the European Union, without seeing new opportunities coming from elsewhere. Many who could sell beyond Europe were already doing so, and Brussels offered little hindrance.

Much of the trade in services remains in limbo. Due to Covid, those that require specialist workers to get to clients on the continent have found it difficult, if not impossible, to move people around. That has delayed the onset of problems with work permits.

At the start of the year, the finance sector in London quickly lost the dominance in European share trading to Amsterdam. Rules for other specialist financial services are still being fought over.

The pledge to get a Memorandum of Understanding for the basis of financial trade post-Brexit resulted last week in a technical agreement to set up a forum for further "dialogue".

Smaller-scale exports

The trade in goods remains the focus for a lot of the difficulties. So far, we only have official figures for export of goods to the EU during January, down by 41% overall. For food, they were down 63%. Meat was down 59% and seafood by 83%.

That looks catastrophic and Brexit critics seized on it as evidence of the problems they had forecast. But the numbers fail to take account of a return to lockdown on both sides of the English Channel, or to the extensive stockpiling that preceded the end of the Brexit transition period. Future export numbers will be closely watched.

Unable to stockpile, seafood was first into the border customs clearance in early January. The industry is working through the difficulties with form-filling for Export Health Certificates, but is still struggling with rules being applied in different and sometimes contradictory ways at different ports and by different customs officials.

Larger companies can get their consignments through in single truckloads. That is true of Scottish salmon, but delays mean it cannot guarantee delivery times for early-morning markets. Fish in trucks for longer are worth less. And without guaranteed delivery times, the risk is of EU customers looking elsewhere, to suppliers who can be relied upon.

Smaller-scale fish exporters take a pallet or five at a time, and multiple consignments require multiple certificates. Just one of them using the wrong page numbering or ink colour can hold up the others.

So prices of shifting pallets have gone up. Some hauliers simply refuse to take produce from Britain back into France, because it's easier to go empty than to get delayed. That is the hauliers' explanation for traffic flows returning close to normal levels. The lorries are often far from full.

Three months on, delays to seafood carry a new risk. With spring, temperatures are rising, and shellfish is at higher risk of going off.

Caught in catch talks

Upstream in the fishing industry, Elspeth Macdonald of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation, says the Covid impact on demand for fish from restaurants has allied with unpredictability of wholesaler customers getting their produce into the European Union as two parts of a continued slowdown of fishing effort.

The other part is that quota negotiations are still going on - the first of their kind between the EU and UK. An overall deal was approved on Christmas Eve, which dismayed the industry by retaining European boats in UK waters for more than five years. That left a lot still to be thrashed out, and that process is taking longer than the industry expected.

"Vessels are working with provisional quota, and there's caution ahead of that negotiation concluding" says Ms Macdonald. "Because of prices, logistics and quotas, some boats are taking the opportunity to get repairs."

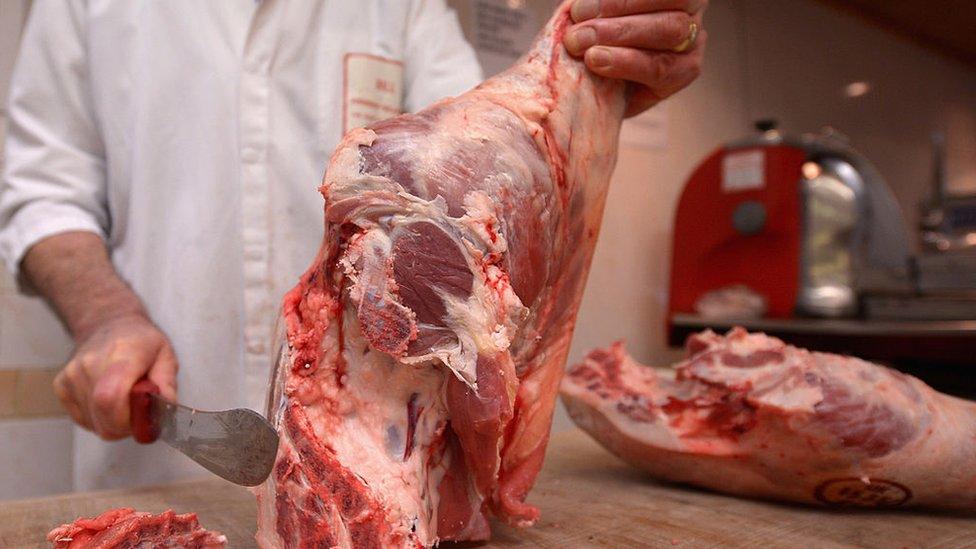

Appetite for meat

The red meat exporters have similar problems, though there are fewer smaller companies using "groupage" of multiple loads on one truck. One company that does is specialist butcher supplier MacDuff in Lanarkshire.

With an estimate of only around 30% of the usual red meat exports going to European markets, the puzzle for economists is why that hasn't left a glut in the market, and a cut in prices. To farmers, sheep and cattle prices are looking unusually healthy.

The answer seems to be that lockdown has increased the British appetite for home-grown butcher meat, though some slaughter has been delayed, at the risk of animal welfare issues.

But it's not all about food. At Scottish Engineering, chief executive Paul Sheerin cannot find any positives that have come out of Brexit, and some of his members feel their plight is being ignored in favour of the food sector.

Engineered goods obviously don't have the same short shelf-life, and trucks carrying them are often passed by those with more urgent need to unload. Scottish engineering firms tend to be smaller and send exports in a few pallets of groupage. Similar problems to food arise with that. I'm told one truckload from Scotland was delayed for three and a half weeks by problems at EU customs. The price of transporting a pallet into the EU went up about five-fold earlier this year. That has subsided, but prices remain two to three times higher than they were last year.

Shift in sentiment

At Terasaki Electric, subsidiary to a Japanese parent firm, 115 workers make components for the energy sector, selling 80% of output for export to the EU and beyond. They located on Clydebank to be near the shipyards. That was 50 years ago, and the company has stayed longer than the yards did.

Managing director Vaughan Turner says Brexit has been "hectic and difficult to manage. We had prepared for Brexit quite well, but when the deal came along, it was different to what we expected.

"Product standards are the same in the UK as in the EU, so that's a positive point. However since Brexit, the requirements for documentation, procedures for clearing goods, in and out, have changed. That takes longer. That costs more. Freight takes longer, so we have to invest more in inventory."

Vaughan Turner says his company, Terasaki Electric, prepared well for Brexit but has still found trading difficult

There are also complex Rules of Origin. A component with materials from outside the EU or UK can carry tariffs, at varying rates, depending how much the materials are altered before being re-exported. So importing an item from Germany, processing it and returning it, can bring a hefty charge on the final leg of that journey.

"Our customers have been quite positive, given that we've been with them for many years," says the factory boss. "But you can definitely see a sway in sentiment towards procuring in the EU. It's costing our clients more too. It's easier, it's cheaper, and this is a big risk for us. If that sentiment takes hold, potentially some of our clients will require to trade with us in the EU, so some of our activity should shift from here to the EU".

"I don't see any advantage in Brexit. Our non-EU business has remained the same, and there is nothing coming down the road to support that business."

Brexit remains a work in progress - its effects often masked by the Covid crisis. With more movement of people, and opening up of commerce, the impact of this enormous shift in Britain's economy is likely to become clearer in the coming months.