Six months of Brexit: Business pays the price

- Published

Fresh food and haulage were first into the front line of Brexit, so how are they faring now?

Some are settling down: others warn recruitment outside Europe is a growing problem, with consequences.

For those and other sectors, including engineering, paperwork, delays and extra cost are harming their relations with European customers.

The story of Brexit can be told in three-word slogans: Take Back Control, Brexit Means Brexit, Get Brexit Done.

So five years after the referendum, and six months from leaving the single market, what's the slogan from businesses most affected? Bureaucracy, delay, cost.

Many businesses aren't much affected. The 10% drop in the value of sterling during the night that results came in has been forgotten and priced in. Most firms don't export. And the focus has been much more on the extraordinary challenges of surviving Covid-19 than on Brexit-16.

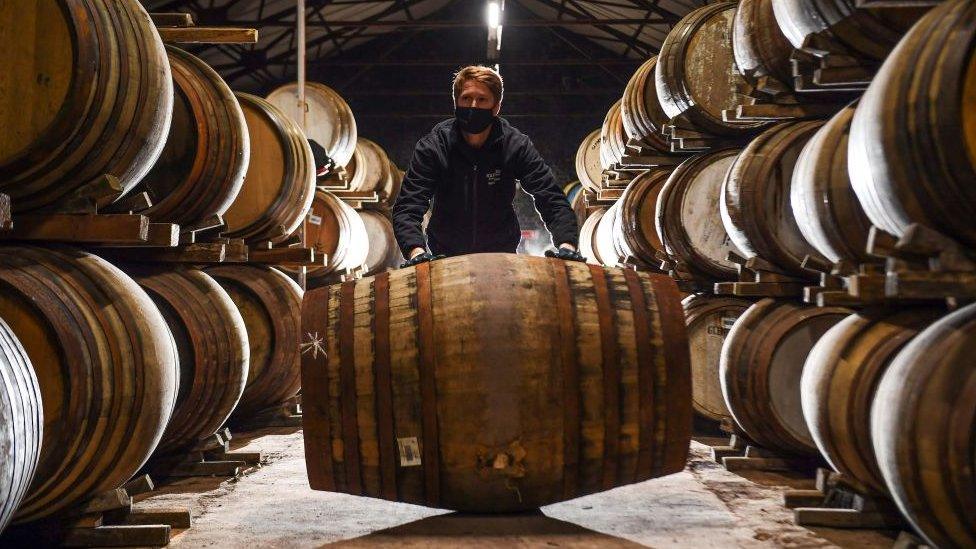

Some businesses look to opportunities from the new regime. Some are already looking to the upside in more distant markets which British ministers are keen to open wider - Scotch whisky distillers among them, looking to an end of Australia's 5% tariffs.

Scotch whisky distillers are looking to more distant markets

But for those who grew out of Britain's close integration into the European Union, its customs union and its single market, the disintegration of that union has left them paying the price.

The Scottish government sought to highlight the problems from Brexit this week, publishing a dossier of negative outcomes, external. It cited evidence from Scottish Enterprise's engagement with 670 importing and exporting businesses between January and April across a range of sectors.

Some 41% of them reported the top challenges they faced at the time were caused by the end of the Brexit transition period, such as transportation costs (cited by 17% of the businesses) and disruption at UK borders (13%).

Covid mask

Over the months, we've reported on those exporting plants, who find themselves completely barred from sending any produce into Europe or Northern Ireland with earth attached to it. Seed potatoes were also completely barred from export into the customs union, though potatoes are not.

We've heard the concerns of berry farmers in eastern Scotland who now lack access to the EU nationals on whom their business model was built, and hotel operators in remote areas as well as cities who depend on skilled European recruits.

Universities which depend on recruiting the cream of European young academics are finding it much tougher to recruit them, where networks and their future careers no longer stretch across national boundaries.

The loss of seamless access for touring performance artists and fashion houses was raised again at Westminster this week, pointing to the loss of cultural exchange, which is apparent also from the difficulty of bringing European artistes to festivals in the UK.

Lockdown restrictions have masked much of the impact of the Brexit project

And while whisky may gain from the Australian deal, we've heard from sheep and cattle farmers who foresee the arrival of meat into the British market without quota or tariff, with industrial-scale production and less stringent standards than those required under current EU and UK regulations.

For the Brexit project, the problem here is that the gains from wider and deeper access to more distant markets will have to be very big to make up for the loss of seamless access to Europe. And they will take time to develop, while the people and firms who lose out do so much faster and make a bigger noise about it.

It is perhaps to the advantage of the project that Covid has masked much of the impact. We cannot know how much exports of food, market prices and disruption of business travel would have changed if hospitality and commerce had continued without the infection control measures in the UK and its trading partners.

But there are some indications of the Brexit effect, in the 19% decline of food trade with the EU in January to April compared with 2018, while non-EU trade fell 4%.

Six months in, I've been hearing from sectors and companies about how Brexit now looks close up.

Unreliable partner

ATL Turbines in Dundee has a niche in servicing large, chunky equipment for aerospace, military and power plant customers around the world.

Dale Harris, its chief executive, echoes the familiar refrain that selling into Europe used to be as easy as selling to a customer down the road. Now, consignments to European customers are more difficult than to Canada or the USA, delayed by incorrect paperwork, often resulting from the failings of fast couriers.

ATL is confident that it will retain customers for its turbines

With a four-fold increase in both import and export paperwork, and each one taking around three times longer, the wrong exchange rate or commodity code holds things up for days and sometimes weeks. There's an admission that the work for European clients has suffered. Doing business with Britain has become more difficult for Europeans.

While the Dundonians get more used to what's required for outbound pallets and packages, the problems persist with inbound: EU suppliers of spare parts and materials are still not tuned in to the bureaucracy.

There's also the issue of safety accreditation - a vital component of work in aerospace. That used to be done under the umbrella of Europe's aviation regulator. Not any longer. And the price of access to European accreditation as a non-EU company is five times higher.

ATL is confident it has a strongly established niche, and that it will retain customers. But finding common cause with the engineering sector more widely, it worries for those whose produce can be easily replaced by an EU-based rival. British exporters into the EU are marked down as problematic and their deliveries unreliable.

Sea of opportunity

Some in the seafood sector thought escape from Europe's Common Fisheries Policy could only be for the better. They're thinking differently now. The deal done last December did them few favours. Talk of a 'sea of opportunity' rings hollow.

As a newly independent coastal state, Britain has failed to get agreement with non-EU northern neighbours on shared catch quotas.

Access to the big EU fish market in Boulogne-sur-Mer was the first to find paperwork was a big problem. Each consignment requires a health certificate, signed by a vet on despatch from the UK. They have to be on paper, not electronic, in certain ink colours, numbered in precise ways, but with these rules inconsistently applied at different border posts.

The UK has been unable to get agreement on shared fishing catch quotas

Big exporters, such as salmon farmers, have got used to the rules, and trucks get through. But they do so with delays for checks which mean the produce has less shelf-life when it reaches the customer, and therefore it's worth less. The inability to promise delivery times has reduced the Scottish salmon premium, though total tonnage has held up well.

Smaller consignments, in so-called groupage, are still not faring well. These are a few pallets at a time, shared in a truck, moving through customs at the speed of the least well prepared paperwork. Hauliers are reluctant to take them on, and prices are up.

Boats tied up

With family roots in Madrid, three generations of the Buesa family have built up an integrated seafood catching and processing company based at Troon harbour, Ayrshire.

These haven't been easy decades for fisheries, but they've never seen anything like this before. Four of their boats have been put on the market, with no sign of buyers.

Jordan Buesa, the third generation who runs the fleet while a semi-professional ice hockey player with the Fife Flyers, says Brexit is behind difficulty in supplying the family firm's chandlery. Marine grade plywood seems impossible to source. So is hydraulic oil. Costs are up, including fuel.

Without free access to European recruitment, he explains the firm cannot crew its boats. They would normally be busy at this time of year, but most of them are tied up in the harbour.

Local crews are self-employed, paid on a catch-share basis, and say their earnings are down by around 40% because seafood prices are so low.

Northern exposure

SB Fish can illustrate how the surreal and politically explosive position of Northern Ireland is having an impact on this side of the North Channel.

The company lands a lot of prawns, langoustine and 'tails' - the least valuable of the species that become scampi. Production of scampi used to be on several sites, but pre-Brexit, these were consolidated in Northern Ireland.

To get 'tails' to the province, SB Fish has to send them to Glasgow for a vet's stamp on a health certificate, and then south to Cairnryan, for the ferry and a check on paperwork when it docks.

What used to be as little as five or six hours from Troon harbour to the factory is now at least three or four times as long. It's no wonder that the Clyde Fishermen's Association reports quayside prices in Scotland can be half those in the province.

Many fishing boats remian without crew, tied up in harbours

For the first time, they're getting complaints about quality once it arrives. Customers are paying less for prawns on the continent, and one phoned up this week to say unreliable delivery times mean they can't order as much.

All that is before a customs post is erected at Cairnryan. The Brexit deal on Northern Ireland requires food arriving on the British mainland will have to be checked for compliance.

The UK Government is reluctant to give the go-ahead for building. But the position remains unclear as Lord Frost, the Brexit minister, locks horns with the European Commission on how the deal should be interpreted.

According to James Withers, chief exeuctive of Scotland Food and Drink trade body, that refusal to check inbound food has frustrated his members. While they have to contend with costly delays in reaching European markets, European suppliers to Britain have been given an unfettered run at the British market.

Parked up

On the frontline are the hauliers. Twenty of the biggest ones, including Scotland's Malcolm Group, signed a letter this week urging Boris Johnson to ease the difficulties they've got with driver shortages and customs delays.

Martin Reid, Scottish policy director of the Road Haulage Association, says the problems in Scotland are the same as elsewhere, and with fewer drivers, delays, rising costs and tight margins, don't be surprised if there are shortages of supplies ahead.

The Government didn't listen, he told me. At the start of the year, it was only concerned about queues at ports and shop shelves being empty. Neither happened. But he warns that we're beginning to head in that direction now.

"A number of members have trucks parked up because they can't get drivers to fulfil their duties. And so it's inevitable that not only will costs of goods go up, but there will be a supply issue as well for some of the goods you see on the shelves."

Hauliers face difficulties with driver shortages and customs delays

Unsettled status

What's next? The political instability of Northern Ireland has arisen from a protocol that put an economic border between it and the British mainland. Grace periods for some of the checks on fresh food going into the province and the European single market are coming to an end.

Some large hauliers who gave Brexit six months to see how things worked out are minded to give up on supplying Northern Ireland, according to Martin Reid.

By the end of the year, engineering firms are facing a change in the regime for testing and certifying their products as safe. The few UK laboratories that handle the tests are at full stretch already.

Delays to implementation of changes to pharmaceutical regulation are coming to an end over 24 months. That could slow up the process of approving drugs (though it did not do so with Covid vaccinations) and implications for supply of medicines from European manufacturers, in the words of the Scottish government, "remain unknown".

Applications for European nationals to get 'settled status' are closed this month. There are concerns for children and older people who may not yet realise that they could be deported without the right to remain.

The consequences of new trade deals are becoming clearer, and a new form of politics in Britain is emerging around trying to influence trade policy.

The secretive ways in which deals have been done so far, without the promised, independent Trade and Agriculture Commission, will come under pressure inside politics, as well as from UK and foreign business and pressure groups on labour rights and the environment.

We're moving from the short term, mixed up with the impact of Covid, into the medium term.

Is Brexit done? Far from it.