From one Acorn, can 20,000 jobs grow?

- Published

There are big claims being made for a mega-project planned for the Aberdeenshire coast, using technology to capture and store carbon dioxide, as well as making hydrogen.

This is part of a bidding process for £1 billion of UK funds, put back on the table after being withdrawn. The 'Scottish cluster' is seen as having the advantage of pipelines and storage.

There's controversy, however, as the project would provide a green light for continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels.

Imagine if you could capture all the carbon dioxide being pumped by industry into the atmosphere.

Then imagine turning it into a kind of sludge and burying it deep under the seabed, making use of North Sea oil and gas pipelines, and those subsea fields that have been emptying over the past 50 years.

Better still, imagine if you created a giant vacuum pump that sucked carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, to add to that sludge.

And instead of heavy transport depending on diesel, imagine if you could manufacture hydrogen for fuel cells, using oil and gas from which the emissions would be captured and stored.

There's a lot more than imagination going into such plans.

This is the proposal being set out for a coastal site in Aberdeenshire, and spreading far beyond, in something called the Acorn project.

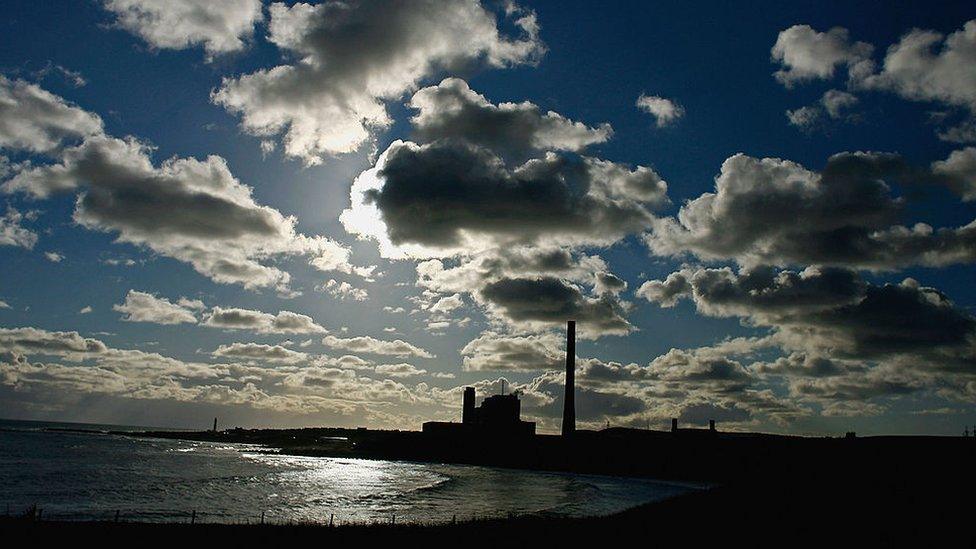

The infrastructure put in place for the oil and gas industry would have a new lease of life under the plans

To help fire the imagination, the Acorn project commissioned an economic model of how it might generate jobs.

Between a lot of construction and then operations, it is reckoned that the project could peak at around 21,000 direct and indirect jobs.

On average, taking into account the peaks and troughs of construction work, it would be closer to 15,000 jobs over the next three decades.

Heavyweight backing

If it works, it would not only generate jobs but it could make a sizable dent in our climate changing challenges.

And the bit that really attracts industry is that it could do so, with a licence to continue extracting and burning oil and gas.

You can probably begin to see why the idea has won a lot of heavyweight support and investment.

Acorn is a consortium comprised of oil and gas giants such as Royal Dutch Shell and financiers such as the sovereign wealth fund of Singapore.

Of all the ways of achieving Net Zero, on a cost spectrum starting from building insulation, across solar and wind power, carbon capture and storage is among the most expensive.

And what it still needs is a big slice of £1bn of infrastructure funding on offer from the UK government.

The CO2 produced by Peterhead power station has been the focus of a number of green projects over the years

Acorn is one of four projects understood to be bidding for the first tranche of that funding, against one in north-east England, another in South Wales, and one that would sequester the carbon dioxide off the coast of north-west England.

Sub-sea reservoirs

Those who have followed the fortunes of Scotland in turning green opportunities into green jobs will note that it has a disappointing track record, particularly when it comes to industrial processes and manufacturing.

They will further note that the UK government has been here before - offering £1bn of funding to the best project for carbon capture and storage (CCS) and then withdrawing it, in 2015, when George Osborne's budgets got too tight.

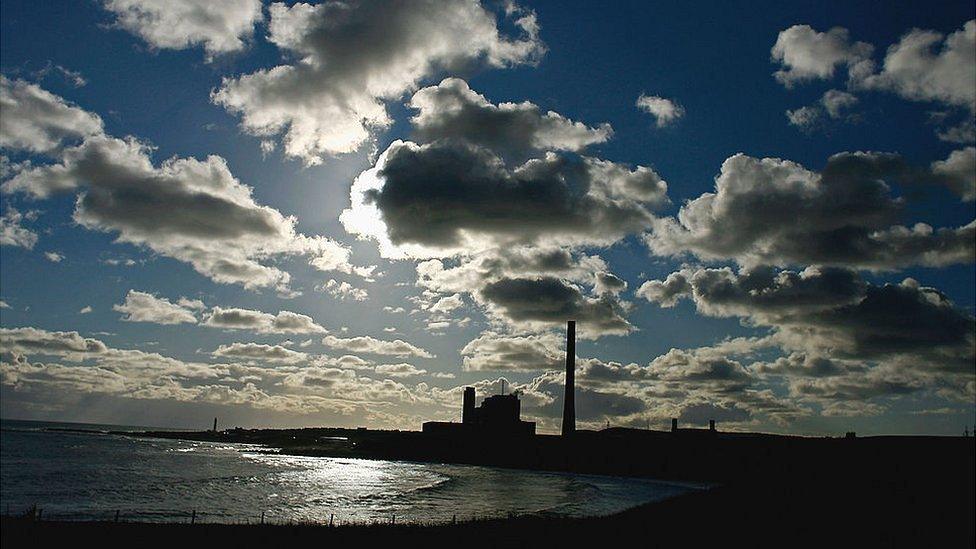

The St Fergus plant near Peterhead processes gas from North Sea installations and could play a part in project Acorn

Such people might prefer to treat the plan with some scepticism. They are unlikely to be reassured by the UK government's super-branding of these projects as "SuperPlaces".

That said, this is what it might involve:

• Based at the gas terminal near the village of St Fergus in Aberdeenshire, where more than a third of Britain's gas comes ashore, a lot of new plant would be installed to process the CO2. The treated CO2 would be pumped into disused or emptying oil and gas reservoirs deep under the sea bed. According to Acorn, this set-up could store the equivalent of 65 years of the UK's 2018 emissions.

• The gases would be gathered from industrial users of energy, including Peterhead gas-fired power station and whisky distilleries in the north-east. CO2 could be imported by ship into Peterhead harbour. A big element of the project is a memorandum of understanding signed last week to team up with Ineos and Petroineos, the owners and operators of the vast Grangemouth refinery and petro-chemical plant.

• From the same base, a new industry is envisioned which would see oil and gas burned to electrolyse water and create hydrogen. That has many uses as energy, most effectively and efficiently for industry and heavy transport and possibly for heating buildings. But creating so-called 'blue hydrogen' from oil and gas is really not liked by climate change campaigners at all. Especially when 'green hydrogen' is seen as an attractive alternative as it can be created by use of renewable power.

• A bold new technology of 'direct air capture' is being trialled, filtering carbon dioxide out of the air. It remains some way off commercial application. You can read more about it here.

Hydrogen jobs

Bids for UK government funding required an estimate of the job impact of such plans. Today, we learn of the numbers, and how that average figure of 15,100 jobs is derived.

Of those 6200 would be direct and 8900 indirect. Most would be in the hydrogen end of the plan, and between next year and 2036, around 60% of the jobs would be in construction.

The biggest job impact is foreseen in hydrogen production.

And Acorn lists the many sectors of the economy that would be involved in the supply chain, beyond construction, chemicals and engineering design to gas and electricity distribution, retail trades, cement, plastering, real estate, accountancy and insurance.

Will it happen? It's a big ask technically, and on several fronts. Nothing like this has happened on a commercial scale.

The Scottish Events Campus in Glasgow will host the COP26 conference in November and the role that the UK is playing in tackling climate change will come under scrutiny

It's also a big ask of government, when it hasn't yet figured out how it's going to distribute its subsidy. It could also put pressure on Scottish and UK governments to co-operate.

Two British projects are meant to get the go-ahead by the middle of this decade, and two more from 2030.

But there's a clock ticking loudly - on the need to tackle climate change, and reach targets for Net Zero.

Its backers say such projects are essential to meeting those wider, bigger targets. And only four months from now, eyes will be on Glasgow and the COP26 summit.

Britain needs to be able to say it is making progress on such projects, if it is to have authority and momentum in the geopolitics of summitry.

- Published11 May 2021

- Published25 November 2015

- Published24 June 2021

- Published24 August 2020