Balancing the books

- Published

The ritual, annual battle over government expenditure and revenue figures for Scotland could take a break because this year's numbers are so extreme. But it hasn't.

Closing the gap either requires lower spending or higher tax revenue, and the spending level is either baked in or politically hard to shift. So attention shifts to tax, which isn't currently as weak as sometimes portrayed.

A notional deficit doesn't have to matter. It does so only if it is to become the real thing. Tackling it requires a plan and some difficult decisions.

Of everything the Scottish economy produced in the last financial year, 22% had to be borrowed to pay for public spending.

The UK level was at 14%, the highest since World War Two. A sustainable level is usually seen as 3%.

You can cut the numbers lots of other ways. Some £17bn more in Scottish spending, and £3bn less in taxation.

And underlying the figures, a dramatic shrinking in the output of the Scottish economy last year, down by £17bn to £162bn.

Thus Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland, or GERS, has given us the figures for a year like no other.

If you prefer your numbers per head, statisticians at the Scottish government tell us of a rise from £15,003 spending per Scot in the year preceding the pandemic, to £18,144 last year.

That's £1,828 more than the UK spend per head during last financial year - slightly higher than the year before.

Tax take per head was down by £600, to £11,500. Offshore oil and gas contributed only £101 of that, and the overall per-head tax revenue was £382 below the UK figure.

The Barnett formula funding is based on population size

What are we to make of that? Perhaps just a profound wish that we don't have another year like that any time soon, or ever.

The current year, 2021-22, will see continuing pandemic costs, including the closing months of furlough, the continuing vaccination programme, and a catch-up spend for delayed treatments on the NHS. The costs may spill into years after that.

But this is such an unusual set of circumstances that it is tempting to park the 2020-21 GERS figures, and the usual hostilities over their implications for Scottish independence. Yet that debate rolls on, by the choice of both sides.

For one side, GERS appears to shows that Scotland's economy is weaker than it should be. For the other, it shows Scotland needs to be part of the UK.

It doesn't prove either point. But if a notional deficit is a problem (and it only becomes one if it might cease to be notional), then GERS is an annual reminder, with or without the Covid billions, that there is a structural cause.

Expenditure is set relatively high, because the Barnett formula for Scotland (as well as Wales and Northern Ireland) has built in higher spending levels per head than England. There's nothing the Scottish government could do about that, unless it voluntarily gave up some of its block grant. That doesn't seem likely to happen.

At £1,800 per head more than the UK average, that spending bonus is the main reason for the notional deficit. The tax revenue, at less than £400 per head lower in Scotland, does much less to explain it.

Tax take per head is not that far from the UK average. And reflecting weaker tax bases in other parts of the UK, the Office for National Statistics can show us that the notional deficit per head is considerably higher in Northern Ireland, Wales and north-east England, as well as being bigger in north-west England and the West Midlands.

In other words, Scotland does relatively well out of spending, but it is far from being an outlier on deficits. The figures tell us that most parts of the UK depend on fiscal transfers out of the three net contributors; London, south-east England and eastern England.

Such transfers are common across countries. They are also applied within Scotland.

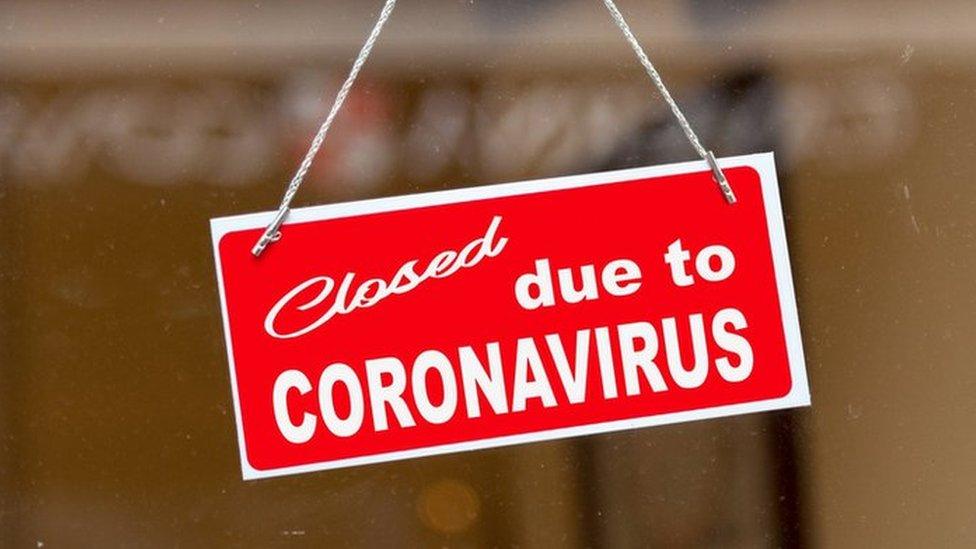

The figures for the last financial year were extreme due to the global health crisis

If spending is baked in, and if closing the notional deficit is a goal, that puts the focus onto tax. Holyrood has gained taxation powers, and has made cautious moves towards using them to diverge from the UK Treasury's tax regime.

One problem is, as the Scottish Parliament's information centre (SPICe) reported this month, it's possible to tax high earners more, but not to get the full benefit if the tax base is relatively weakening.

The block grant from the Treasury reflects that slower growth in income tax revenue. The gains from higher tax rates are offset by the reduced transfers resulting from no longer being income taxed by Westminster.

SPICe put numbers on that, reporting the tax take from higher earners pushed up revenue by a total £900m. But due to the relatively weakening tax base, the balance was of an extra £170m being available to spend compared with the budget if income tax had not been devolved.

It's not that great an advertisement for devolved taxation.

Tax the rich?

However, the case for more borrowing and taxation powers was the response to GERS from the finance secretary, Kate Forbes. She argues that Westminster has 70% of taxation and 40% of spending, and with limited borrowing powers, the SNP government at Holyrood does not have the levers to get the deficit down on its own terms.

If Kate Forbes did have those levers, it would force her to take decisions on how to raise taxation or cut spending, or both. Borrowing on Scotland's own account would also require a reckoning with the financial markets, which could see Scotland as a riskier prospect than the UK, meaning higher interest rates.

Squeezing expenditure, by increasing it at a slower pace than economic growth, was seen by the SNP's Sustainable Growth Commission as necessary for perhaps ten years to get the deficit into sustainable territory. That would be an uncomfortable fiscal start to the independence era, with high expectations for extra spending and added costs from the transition process.

How about raising tax rates? Surely the well-off can pay more? That has a habit of slowing growth, so that revenue is also slowed. Not always, but often. Meanwhile, the well off, or their money, can also be mobile in the face of rising tax rates.

Scottish finance secretary Kate Forbes previously sat on the Growth Commission

Raising growth levels, to boost the tax base, is obviously the preferable option (though some Greens might argue that usually comes at an environmental cost, and 'no growth' is better).

That's where the Growth Commission left a lot of work yet to be done, calling for further work on productivity, and shying away from the tricky question of how tax rates should be deployed: lower to boost growth but at the risk of increasing inequality, or higher to boost revenue but at a cost in growth?

As a backbencher, Kate Forbes sat on that Growth Commission. It was set up five years ago, and reported in May 2018. Now as cabinet secretary for finance and the economy, she has a new group of advisers: 17 people preparing the way for ten years of "economic transformation".

Not all supporters of independence, they are being asked to "unleash entrepreneurial potential and grow Scotland's competitive business base".

This will feed into a post-Covid "transformative" recovery plan, for publication this autumn.

It could help to raise the tax base and close that notional deficit within the UK, leading to GERS being a more comfortable read each August.

Or the plan could be the vehicle on which the SNP sets out a new economic prospectus with which to fight an independence referendum.

Either way, there's a lot riding on it.

Related topics

- Published18 August 2021