Blah Blah Blether in the Blue Zone

- Published

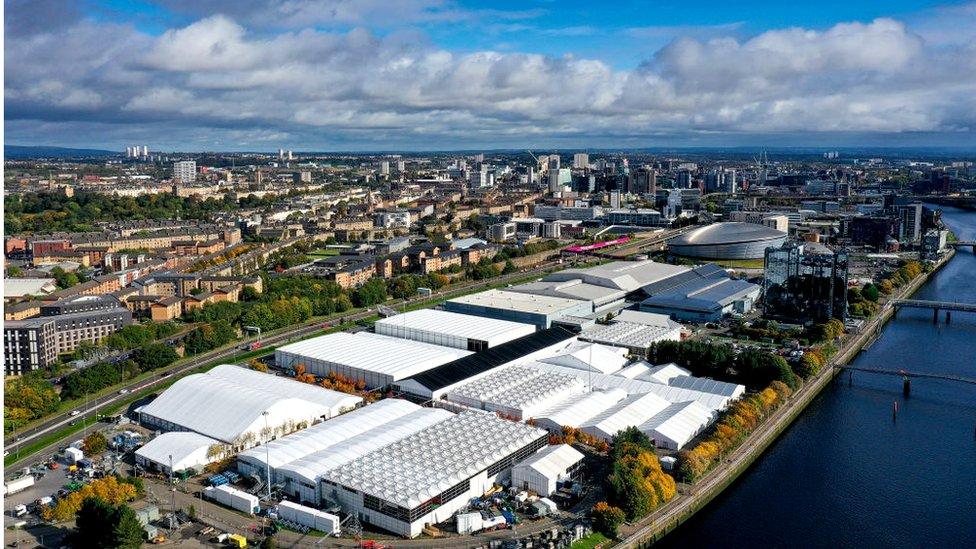

A strip of land on Clydeside has ceased to be Scottish for a fortnight, except for its food and drink - so what is going on behind the heavy security at the COP26 summit?

This is far more than a gathering of governments. Most of the activity is a festival of political action, and a trade fair representing many billions in potential business deals.

While protesters rail against the shortcomings of the past 25 COP gatherings, representatives of the movement to tackle climate change are inside, having been invited into the heart of the discussions.

When Glaswegians blether about a blue zone and a green zone, they're probably talking about football. But for two weeks, this is not about Rangers-Celtic rivalry but about climate change.

A short stone's throw westwards from BBC Scotland headquarters to the Science Centre, the green zone is open to the public for exhibits and discussions on what is to be done.

A longer stone's throw in a northerly direction would land in United Nations territory. It would be unwise to lob stones, however, as the security is fierce, the fences are high, and vessels patrol the Clyde with military menace to those who wish to disrupt the Cop26 summit.

The Blue Zone contains exhibition and meeting spaces as well as pavilions offering a programme of events

I went through the queues and airport-style security, entering this small blue strip of Clydeside that is non-Scottish for a fortnight.

And I can report that it's a fascinating gathering of humanity - every country and race represented, numerous languages spoken, and 28 currencies so far exchanged in the NatWest branch. (Most delegates and observers arrive with US dollars or euros, the manager tells me.)

Inside the blue zone, there are people from all over the world, checking their phones

The summitry was at its highest peak on Monday and Tuesday, when the heads of government were whisked in, made their three-minute speeches, and were whisked out. Their Excellencies' departure left negotiating teams for 10, or 11, or maybe 12 days to grind through the voluminous detail of what each country is offering if they are to fulfil the pledges and meet the targets set six years ago in Paris.

That process is mostly done in private and in numerous meeting rooms around the Scottish Events Campus. The public face of it is in plenary sessions in two vast marquees, named after two of the higher peaks in Britain - Cairn Gorm and Pen y Fan. They're summits. Get it?

Gigantic gabfest

Seats are set out with social distancing in mind for each UN member state. Delegates for each country tend to travel in packs, bristling with self-importance, their imminent arrival at plenary sessions signalled in advance by vibrations in the temporary floor.

Many more seats, further back, are for representative groups of civil society, and of the many offshoots of the UN. The deals may be cut by the big players, but the seating plan is designed to signal that this is inclusive.

And that's where the rest of Cop26 comes in. Blue zone passes are prized, and hard to secure, but this is an event intended to welcome in the world for a gigantic gabfest about climate change.

It feels busy, with people milling and jostling along the long corridor spine of the campus, Where it widens, there are work stations and chairs set out to encourage conversation or to offer a rest. Anywhere, you can find people squatting by a wall, checking social media or earnestly engaged in Zoom calls to who-knows-where.

Unmet promises

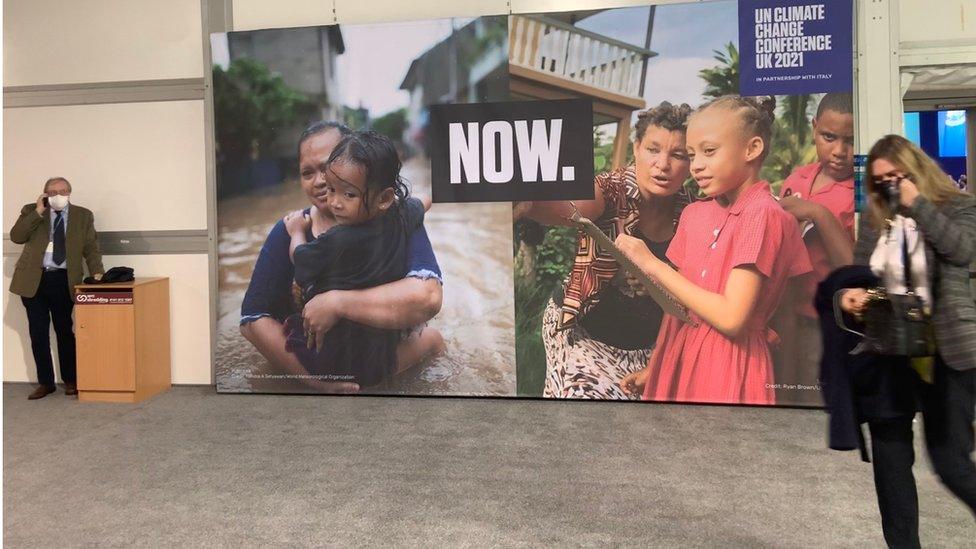

The Hydro, designed for very large concerts, has been turned into an 'Action Zone', with 'Action Hubs'. Slogans exhort attendees: 'Race to Zero', and 'We can do this if we act NOW'. Some simply reduce that to the slogan 'NOW'.

A giant and beautiful globe, perhaps 10 metres wide and featuring the world's weather systems in perpetual daylight, hangs from the roof and spins slowly.

'Action', in hubs and zones, turns out to be entirely about talking. And talking. And talking more.

In small groups, around tables, to audiences and down the barrel of lenses. Around TV cameras, technicians wait wearily and presenters check their studio-quality hair.

Far more activity is through streaming links to the worldwide web of climate change activists. Numerous bloggers and vloggers are in selfie mode, transmitting their efforts and insights back to their supporter bases in distant lands.

This is the NGOcracy: non-government organisations which are drawn into the conversations between nations. While activists seek protest and grandstand outside the perimeter fence, and rail against the 'blah blah blah' of the government representatives inside, the uncomfortable truth for them is that their people are literally inside the tent.

In a vast hall of two-storey pavilions, the Peatland Pavilion is next to Ghana's and the Indigenous People's Forum. The Climate Vulnerable Forum is next to Korea, Scotland and Turkey, and not far from WWF pressure group. Compassion in World Farming adjoins five central Asian republics.

Global goal

There is a water pavilion, near one for the cryosphere (the earth's receding icy bits). Poorer countries offer little more than flags, leaflets and reproach for promises unmet, while Qatar and the UAE flare and flash their oil and gas wealth for all to see.

Europeans, who seem to dominate the crowds and discussions, play down their state of global privilege, with pavilions designed for, well, more talking. France goes for a minimalist, stripped down wooden stockade. Germany has little more than a TV studio.

The UK is branded with capitals 'GREAT Britain'. Having the presidency, it gets the best location - next to the vast United Nations pavilion.

Throughout the day, each pavilion has a programme of speaker events. But quietly. To avoid clashing speeches in neighbouring pavilions, audiences listen through headphones.

This is also because so much of the discussion is being streamed online, and some contributors beamed in from far away. In the Armadillo concert venue, its 3,000 seats are cordoned off with yellow tape, and its wide stage set out only for the cameras.

The summit has its own 'side events', with titles that demonstrate how a complex organisation can squeeze the life out of language: "Informal consultations on matters relating to the forum on the impacts of response measure", and another on "'the second periodic review of the long-term global goal".

There is a more digestible prospect from ProVeg Deutschland: 'It's time to address the cow in the room: we want diet change'.

There is business too. Lots of business. Its pavilion is next to a small section for a group drawing attention to the plight of the Congolese forest. But its presence is much more pervasive.

Primary sponsors and supporters of the United Nations organisers include Microsoft, NatWest, Scottish Power, SSE, Sainsbury's, Sky and Unilever. On display, there is a hydrogen powered double-decker bus made by Alexander Dennis in Falkirk, and an all-electric Jaguar. The brand with the best product placement, however, is Dettol. The masks and constant cleaning remind you this is a gathering with big infection risks.

In numerous meeting rooms throughout the campus, they're talking deals. Billions and billions of dollars, euros and pounds are in search of green projects, and finding quality ones can be hard to pin down.

By happy coincidence, many of the 'observers' have projects to promote - including city and regional governments, power companies, transport and data innovators. They are in search of those billions.

Grab and go

So Cop26 is at least three-fold; the ultimate government summit on co-ordinating a response to the world's biggest challenge: it's a gathering for the global environmental movement: and it's a trade fair for businesses and banks that are plugging into its potential for making profit as well as doing good.

What gives it added energy is the expectation that this Glasgow Cop must set the pace for the decisive decade, and that this is the first time such a gathering has been possible since the pandemic struck. As a representative sample of the world's people, you can sense the relief at being able to meet up, and be social animals.

There's less pleasure taken in the amount of queuing. To get in, snaking queues leading to airport-style security last up to an hour at their morning peak. They feature highly unBritish queue-jumping.

Once inside, the only sign of being on UN territory is that British police are gone, and replaced by brown, American-style security uniforms.

And the only sign of being in an enclave of Scotland is the food, for which more queues are a feature.

In seeking to reduce food miles, the UN doesn't do world cuisine. A huge black-draped eating hall is dominated by a sign simply saying 'Fish and Chips'. This is Peterhead-landed, says the menu, and for £8, you have also to account for 1.1kg of carbon dioxide.

'Grab and Go' stalls are a further showcase for Scottish fare; vegetarian broth at 0.1kg of CO2 or a venison roll at 0.7kg.

Do the delegates and observers in this Conference of Parties 26 appreciate the local food? They don't have much choice. Like any other, this environmental army marches on its stomach.

Only one staple of the Scottish diet is left when everything else is consumed - shelf upon shelf of Irn Bru.