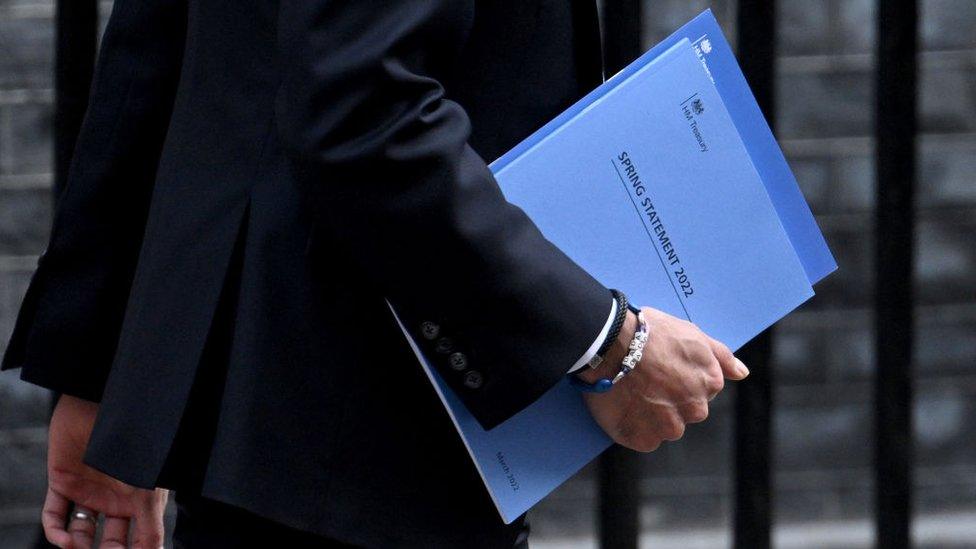

Spring Statement: The state and the kitchen sink

- Published

How far should government go to provide security for people and businesses at times of crisis? When the pandemic struck, it threw everything at tackling it. How about price inflation and economic warfare waged through energy prices?

"I cannot protect everyone from the global challenges we face." So said Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, responding to a high expectation that he should do more to mitigate the impact of high price inflation.

It was followed up with a TV interview expanding on the theme. "It's the hardest part of this job, not being able to doing everything that people want us to do. I can't make every problem go away. Where we can make a difference, we want to."

And yet, there are inevitably ways the chancellor can make a difference and chooses not to. He is in the political business of making choices. He could have made a difference by raising welfare benefits in line with inflation, but chose not to.

Two years from now, there's to be an income tax cut (not for income tax payers in Scotland), reducing tax on better-off pensioners and those with wealth, while adding National Insurance costs to those who work. That's a choice as well.

The Spring Statement was also about the politics and economics of managing expectations. It sought to answer the challenging question: what can and should government do in support of people when they hit a financial crisis.

Behind the statement was a chancellor trying to carve out a reputation as a fiscal conservative, in contrast with his Downing Street neighbour, whose fiscal flexibility has left some Tories deeply disoriented.

When you combine all the measures the UK government has taken since October to help households with price inflation, the Office for Budget Responsibility says they offset about a third of the financial impact people are facing from rising prices.

Cushioned effects

Contrast that with the onset of the pandemic. The response was to throw the kitchen sink at the health and economic challenges.

When people were calling for 75% wage support in the early stages, Mr Sunak went further, with 80% furlough. When they wanted him to extend it, at first he said no, and then went further than expected. Business wanted loans. They got more than they asked for.

Early in the pandemic, Mr Sunak provided 80% wages support for businesses

Getting through Covid became a collective national endeavour, as it did in other countries. It was an exceptional pressure, requiring exceptional responses.

What about now? It is not just that prices are rising rapidly, but that energy prices in particular are being used as a weapon of economic warfare. Orchestrated from the Kremlin, that financial instability reaches into everyone's home.

So the big question is: how much should government do to cushion the effect on individuals and on businesses?

The answer from Rishi Sunak is: it should help, but not to anything like the same extent as a pandemic.

Stagnating incomes

Naturally, this is about party politics. The Tories see themselves as the party of low tax. Yet Rishi Sunak is one of the biggest tax-raising chancellors of the modern era.

His response to Covid was far beyond the portrayal of wildly excessive borrowing that Conservatives sought to pin on Labour under Jeremy Corbyn.

Mr Sunak has taken the share of Britain's national output that is absorbed by taxation to its highest level since the 1940s, when the nation was shifting from a wartime footing.

Nor can Tories easily claim to be the party of prosperity. The Institute of Fiscal Studies' analysis of the Spring Statement notes the impact of stagnating incomes since 2008.

With the financial crash that year followed by tight credit, then poor productivity growth, with austerity budgets hampering growth, then going into the pandemic and an inflationary crisis, median earnings have barely changed.

They have stuck beneath £30,000 per year. Yet if incomes had continued to grow on the trajectory before 2008, the IFS says that median worker would be on an additional £11,000 a year.

'Roll back the frontiers'

So claiming to be the party of low tax or of prosperity is going to be a struggle against Labour, the SNP or Liberal Democrats at the next Westminster election.

Where else might the fault lines lie? Thatcherites may hark back to their hero's call to "roll back the frontiers of the state".

Individual freedoms and responsibilities play a more prominent role in that Tory ideology. The state's role as a provider of security in people's economic lives, which was stepped up for the pandemic, is now being stepped down again.

Perhaps Rishi Sunak is trying to feel his way towards a boundary between the state and the individual with which his party and the country can be comfortable.

His political opponents have an opportunity to respond with their own.

- Published24 March 2022

- Published24 March 2022

- Published23 March 2022