Gers: Public finances feel impact of extraordinary times

- Published

The pandemic has had a massive impact on public finances

Two exceptional years of Covid left the public finances in a very different state - for the UK, Scotland and every other country. Gers gives us an indication of just how different in Scotland, as the impact from year one was partly unwound in year two

A higher level of public spending per Scot goes much further to explain the larger gap between taxation and spending than the UK as a whole. The gap in parts of England has more to do with a weaker tax base

The rise in offshore oil and gas tax last financial year helped to narrow the gap, and next year, those revenues will present a very different picture again - just as the SNP wants to be setting out its case in an independence referendum

These are extraordinary times. An unprecedented pandemic has been swiftly followed by an energy crisis and inflation taking off.

There's nowhere that makes more impact than the public finances. With lockdown, businesses closed, transactions dried up, profits shrank, income and travel was down. Taxes plummeted.

Spending went up on health, business support and employment grants. The gap between the two soared, and that had to be funded by government borrowing. The same is true for most countries.

We're now seeing the impact on Scotland's public finances from two years of Covid.

In year two, 2021-22, taxation rose again as people started earning and spending more. Tax holidays for some businesses were wound down. Spending fell, as furlough was curtailed and businesses required less support, even though the cost of vaccinations was up.

After a 2020-21 gap between public spending and taxation of more than a fifth of the entire output of the Scottish economy, the gap for 2021-22 fell sharply, to just over 12% of total output.

It's that share of GDP that offers a clearer and more comparable indication of the scale of the deficit Scotland would have faced if it had a stand-alone budget.

The UK's public sector deficit fell to half that scale.

For comparison, the Scottish notional deficit in the year before the pandemic ran to nearly 9%. The European Union offers a benchmark, by expecting its members to go no higher than 3% of total output, or gross domestic product. But the pandemic ran a coach and horses through that rule.

As we've seen before, Scottish tax revenue per head or as a share of the economy - if you include oil and gas - falls not far short of the UK level. That indicates that these figures do not suggest the economy is significantly under-performing the UK as a whole.

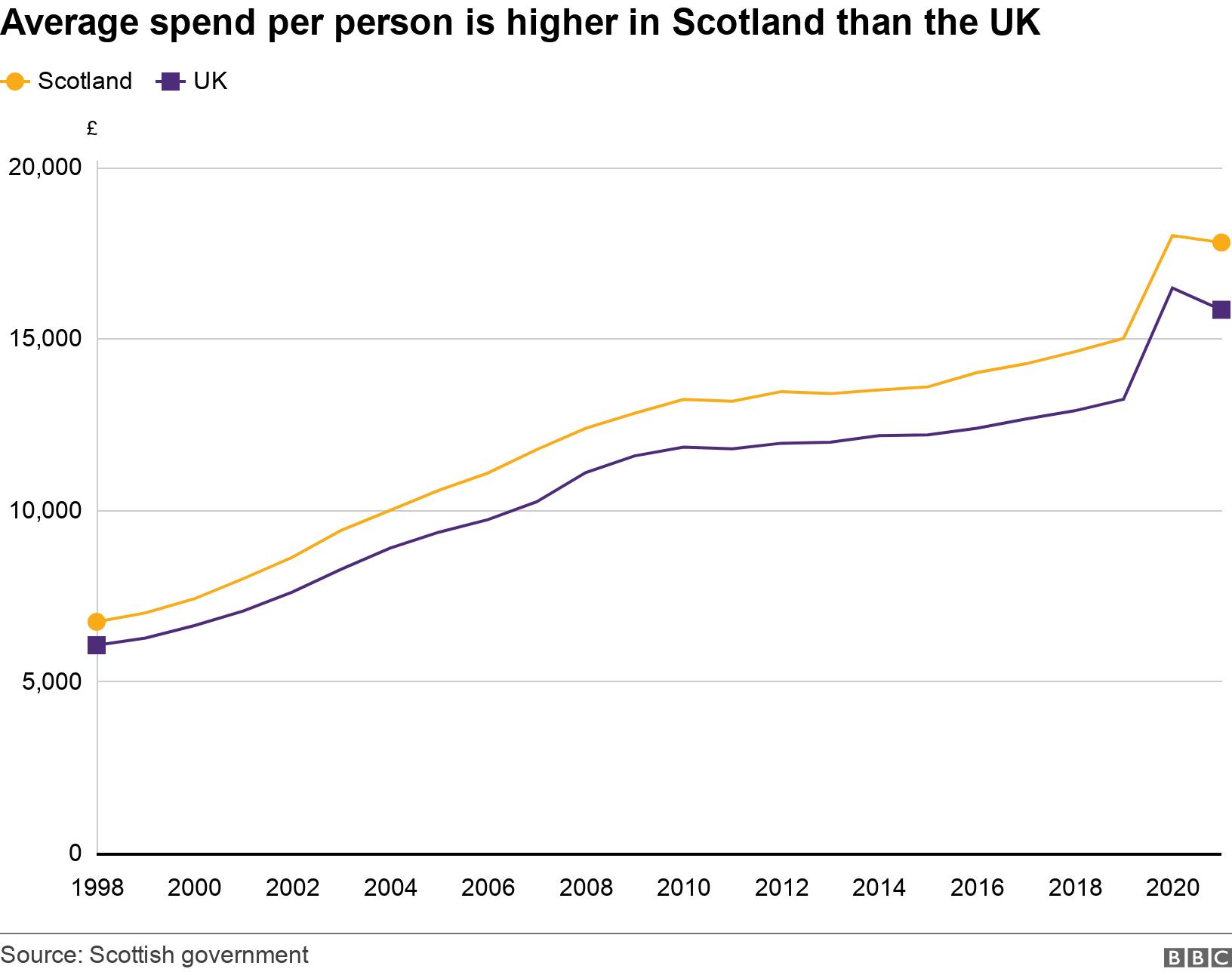

It is in spending that the big differences are more apparent, and these are baked in to the numbers through the formula for funding Scottish public services, as well as those of Wales and Northern Ireland.

Measured per head of population, the average Scot has roughly £17,200 spent on them by different layers of government. That's nearly £2,000 more than the UK figure per head.

And that is where these figures get awkward for the cause of independence. Higher spending per head is baked in by the funding formula, and justified by Scotland's different needs, for worse health and rural services.

The Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (Gers) report was first published 30 years ago, as a Conservative government method of countering the case for a devolved parliament in Edinburgh.

It has been refined by government statisticians over that time and, for half its life, it has been published by the Scottish government under SNP ministers.

In the early part of last decade, the numbers looked much healthier because oil and gas revenue was significantly higher. That rosier outlook was used by the SNP and Scottish government in making the case for independence at the 2014 referendum.

Since then, the party's own Sustainable Growth Commission observed that oil and gas revenue should not be used to fund day-to-day spending commitments. It is a windfall, the advisers said, and should be put aside in a separate fund.

The party hopes to go into an independence referendum in 2023, and can anticipate doing so with a much stronger set of figures when Gers is published this time next year. The tax on bumper profits from oil and gas, including most of the £5bn take from the windfall tax, could push Scotland into a surplus.

After falling close to zero, the current estimate of offshore oil and gas tax is of a rise from £3.5bn last year, when the oil price rose from below $20 to nearly $120, to £13bn from oil and gas in 2022-23.

And with recent movements in oil and gas prices, that could easily be exceeded. Offshore Energy UK has pointed out, just as Gers was published, that gas production, as well as the price, has soared this year.

It will be interesting to see if the energy taxes are used in the same way as the 2014 prospectus for independence, or if the Growth Commission's advice is headed.