Recession: Is it as bad as it sounds?

- Published

Don't worry. Recessions are normal, and merely numbers. The reality is specific to you and your employer, and most firms make it through to the other side. This one may seem to loom ominously, but you're already living through it, and may have contributed to it.

This one is forecast to be long and shallow, and that reflects three big differences: it comes with inflation and rising interest rates, the jobs market remains tight, and there is a risk that government action on tax, spending and borrowing makes it worse. We'll learn more from the Chancellor next Thursday.

Is the UK in recession? Probably. Does that matter? Well, it may sound callous, but... not really.

No-one loses their job because the statistics tell us we're in a recession, or heading for one.

What matters is how an economic downturn affects people and not statistics. And you're probably wondering how it affects you, your employer or your business. While it will be very tough for a minority of people, where they lose jobs or businesses fold, the chances are that you'll be OK.

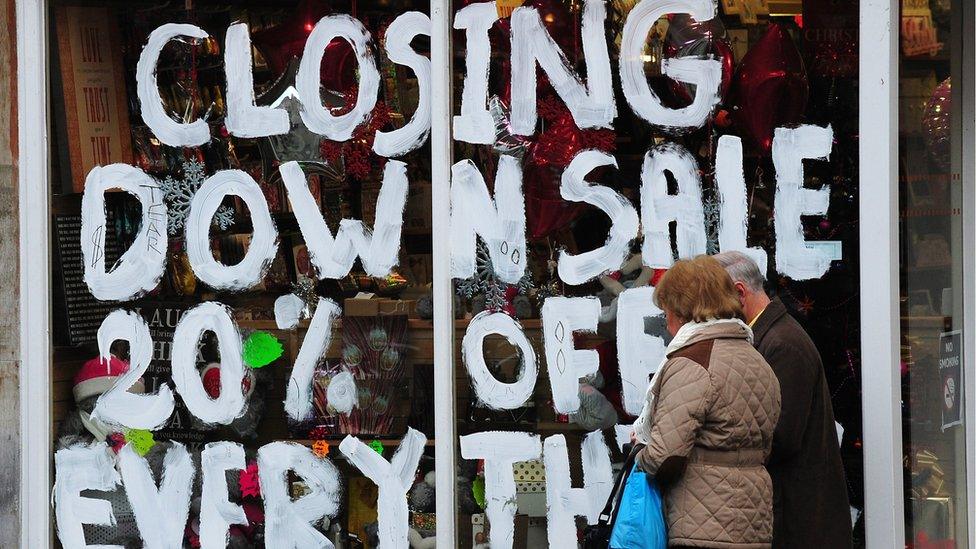

In a recession, weaker companies fail and people are put out of work. That can be because sales revenue drops, so that they can't meet their costs including the servicing of their debts. It can be because the market they're in is in decline, and they have failed to make a move into growing markets.

But most firms battle through and survive, some with reduced revenue, many with losses or reduced profits, and often with reduced employment. Some can even thrive. It's a good time to be an insolvency practitioner.

Survivor businesses can come out the other side in a leaner, more efficient shape, and in a position to pick up the market share vacated by those that haven't made it through.

Recessions and redundancies also have a happier habit of sparking companies into life. Some of the world's biggest tech giants were born in recessions.

So while there is a lot of attention paid to Gross Domestic Product, it matters as a gauge of where the economy has recently been, and how different sectors have been faring in comparison with each other.

The Office for National Statistics says it is in touch with around 40,000 businesses every fortnight, using real-time surveys. It is as thorough a survey of economic activity as we have.

But boiling down those surveys to one number - in this case a drop in output of 0.2% in the third quarter of this year, July, August and September - does not tell you how your business or employer is placed.

Putting two of these numbers together can give economists what they call a recession.

Hunker down

We won't know if this downturn can be given that name for another three months, but the signs are that the quarter we're now in - October to December - will see a contraction in output. If so, that will be the second consecutive quarter of declining output from across the economy.

So in mid-February next year, we may find that we have been in a recession since last July. It is a backward-looking indicator of the economy's strength or weakness.

And the number reflects what you can already see around you, as people and businesses have changed their behaviour.

Firms judge more forward-looking indicators to see how demand might change. If they can foresee tough times ahead in their sector, they pull back on investment, which they have been doing, and perhaps recruitment, of which more later.

For those that look to the "golden quarter" leading up to the festive season to make the profit that can often keep them going through the rest of the year, decisions about stock levels had to be made by late summer.

People also adapt their behaviour. We have heard recently from the property sector that there has been a cooling of house price inflation. Even though supply of homes into the market is well below demand, those bidding to buy are being more cautious.

The most recent Royal Bank of Scotland recruitment survey reflects a fall last month in the number of permanent placements, and the first fall in temporary placements in more than two years. Recruiters may be pulling back, out of caution about what lies ahead, but more significant, the number of people looking to move jobs has fallen. Workers tend to hunker down with what they know when things are getting tough, rather than taking risks.

And if you have responded to rising energy bills by cutting back on expenditure elsewhere, as most of us have, this is not a result of being in a recession. Repeated in millions of homes across the country, that shift in spending, allied to lowered confidence in job security, is the cause of the recession.

In other words, recession is not like a gathering storm that builds up somewhere else and breaks over the economy: instead, it reflects the economic decisions we can see all around us and which many of us are already making with our own finances.

Notorious mini-budget

So, while recessions are not catastrophes, but a normal part of the economic cycle resulting from lots of rational decisions that we ourselves are making, there are aspects of the one we're (probably) currently in that look different. Here are three.

The Bank of England's assessment is that the recession began in the middle of this year, and will run through next year into the middle of 2024 - the longest recession since the were first published, nearly a century ago.

It says that it will be relatively shallow. The last two downturns we've seen have been exceptionally steep and sharp - in 2008, with a property crash leading to a financial and banking crisis, and in 2020 with the sudden jolt of a lockdown due to Covid.

The financial crash left deeper scars than previous recessions, in that the banks are often the drivers of growth out of a recession, and in this case, they were badly damaged, squeezing their business clients hard, and being told to rein back on new risky lending.

What worked well, in that case, was that they were under pressure not to repossess homes where people could not afford mortgage payments. Previous recessions had seen that happen, it pushed down property prices, and worsened the short-term downturn. However, very low interest rates since then have encouraged more lending for house purchase, pushing prices up relative to earnings and ability to pay.

Businesses have also enjoyed a long holiday from costly finance, and with interest rates rising again, some of those who took risks on debt will be left exposed.

The ONS's head of statistics told the BBC Today programme that he is surprised that 4% of firms say rising interest rates are their primary concern. They are more concerned for now about rising energy and supply costs.

The September figures do not tell us much about the effects of the notorious Kwasi Kwarteng mini-budget, which provoked a market spike in borrowing costs. We are more likely to see that reverberate through the October figures, to be published a month from now.

Strike action

A second difference in this recession is that the jobs market starts out exceptionally tight. In other recessions, jobs are shed as companies try to cut costs or as they go bust. Often, those job cuts come later in a recession or after it has, technically, ended.

Economic orthodoxy tells us that the threat of job losses has a moderating effect on demand for higher pay.

That's not evident from the current spate of strikes and threatened strikes, probably because those union members do not see their own jobs as being threatened - most are in the public sector - or they judge that employers are able to pay more than they are offering.

Unemployment is forecast by the Bank of England to rise from very low levels, just above 3% of the workforce in Scotland and just above that for the whole UK, to more than 6% across the UK.

So those calculations on pay and industrial action may yet change. For now, however, recruiters continue to search out people for vacancies, pushing up pay to do so, and taking on apprentices.

Counteract the contraction

The other big difference with the financial and the Covid downturns is the response from the central bank and the government.

In a typical recession, central banks cut interest rates to help borrowers get through and stimulate investment coming out the other side. But this time, with inflation to be controlled, rates are on the way up.

Also in the past two downturns, the UK government used its spending power to boost demand, aiming to counteract the contraction. That has been the orthodox response since the devastating effects of doing the opposite in the 1930s.

In 2009, VAT was cut from 17.5% to 15% (the rate on most goods was later raised to its current 20% level), £3bn of government spending on capital projects, such as roads and buildings, was brought forward, businesses were given more time to pay tax bills, and there was a "cash for bangers" scheme encouraging people to replace polluting older cars with cleaner new ones.

In 2020, the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, opened the spending taps with the furlough scheme and support for self-employed people, with a huge programme of grants and loans for business, and the big boost necessary to get the NHS through the crisis, including (some very questionable) spend on personal protective equipment. He followed up with the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, subsidising restaurant meals for a month.

In both cases, the government faced a steep drop in tax revenue, and opted to borrow on a big scale. This time, following the fiasco of the mini-budget in September, there is pressure to bring borrowing down as a share of national income. And without growth for a forecast two years, expansion of the economy is not going to help ease that ratio.

So this time, we see a UK government stuck between the orthodox response to a recession, which is to borrow and spend to counteract it, and the market pressure and conventional Conservative approach, which is to cut borrowing and the scale of government.

We'll find out next Thursday how Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor, intends to resolve that tension. If he cuts spending and raises tax too sharply in the next two years, he could worsen and lengthen the recession. Removing or sharply cutting the Energy Price Guarantee after next March would contribute to that.

Also for political reasons, he's more likely to save the harsher stuff until after the next Westminster election, which must take place by the end of 2024.

- Published11 November 2022

- Published10 May 2024