Inflation: a tax rise in drag

- Published

If you're getting a pay rise, there's a reasonable chance that you're getting an increase in tax as well.

With public finances in trouble, 'freezing thresholds' sounds like no change, but it's a stealth tax that works best when inflation is high. That's why Chancellors of the Exchequer like it.

Holding steady on a tax threshold, the government can find that the number of people paying it trebles in 15 years - and those already on it pay far more of it.

Prepare for a lot of talk of 'fiscal drag'. It's one of the least painful ways for government to raise tax, because you're less likely to notice what's being done to you.

It works much more effectively when inflation is high.

Often known as "freezing tax thresholds", this is one of the more plausible pieces of speculation - more or less well sourced from the government - about the autumn budget statement being made on Thursday by the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt.

It seems like every other possibility has been reported. And because so much is up in the air, the Treasury has done very little to close down its options ahead of the statement.

One dirty little secret of political reporting is that you can speculate on anything at such times. It won't get knocked down before Thursday. And if it turns out not to be included in the statement, you can claim that it must be because your report provoked a backlash behind the scenes.

The freezing of tax thresholds is more plausible than most examples of pre-statement kite-flying, because it's already happening, through to 2025-26. We're being told that the freeze could be extended as far as 2028.

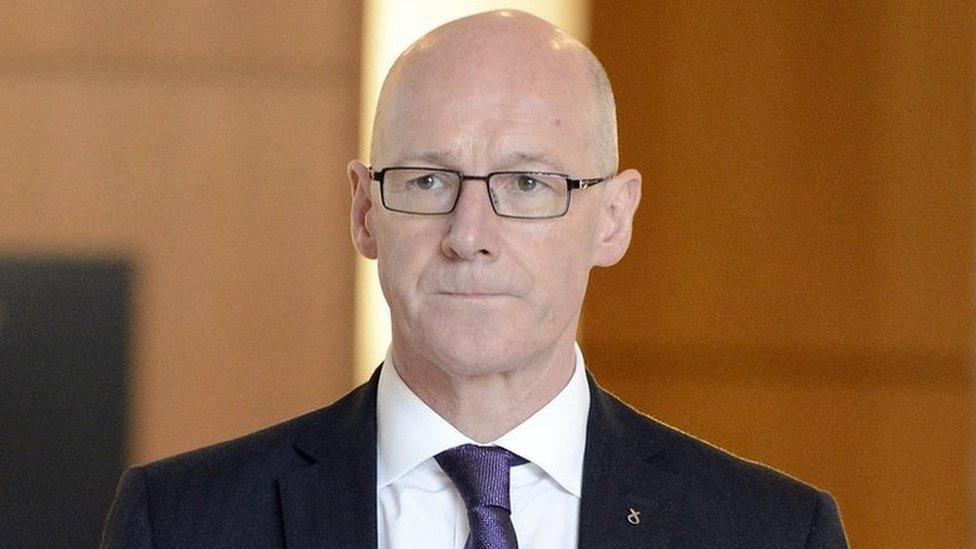

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt told the BBC he wants to make sure any recession is short and shallow

To explain how it works, think about tax thresholds going up at the same rate as wage inflation.

Suppose you are a Scottish tax payer and you're on a salary of £43,662 - comfortably above the full-time average but you're some way short of being loaded.

That puts your earnings on the threshold at which each extra pound you earn is taxed at 41%. So you avoid paying that.

On your first £12,570 of earnings, you pay no income tax. On every pound above that, putting aside any allowances you might get, you pay between 19 and 21 pence in each pound.

Now, suppose you get a pay rise from next April of 5.4%. (Why next April? Because that keeps this example simpler). That is the average UK increase in pay, excluding bonuses, in the year to summer 2022 - the most recent figures we have. It's an increase of £2,358, taking your salary to £46,020.

Well done. If you ignore the fact that prices are currently going up at nearly twice that rate (admittedly quite hard to ignore), then that feels like a pleasant boost to your earnings, so you're probably less inclined to complain about the tax on it.

Or if it means more moola each month than you're used to, you might not notice the tax deduction. Jeremy Hunt would probably prefer it that way, which is why chancellors like fiscal drag.

If the income tax threshold from next April increases at the same rate as average wages, then it would rise to the same point as your new salary. And as you would continue to pay 21 pence in income tax on each extra pound you've earned, your tax bill would go up £495, meaning just over a fifth of your pay rise is handed over to His Majesty's Revenue and Taxation.

But what if the tax threshold is not raised at the same rate as your pay? Instead, what if it's frozen? Each extra pound you earn, starting from £43,663, is taxed at the higher rate of 41 pence. And your tax bill goes up by £967.

The increase in your income tax bill has nearly doubled. You've just been fiscally dragged. And so has everyone earning above that level.

If you pay tax in the rest of the UK, you don't reach the threshold for the higher rate of income tax until your earnings pass £50,270. That moves you from paying 20 pence in every extra pound earned to paying the higher rate in England, Wales and Northern Ireland of 40 pence.

A similar illustration for the rest of the UK: an average pay increase would add £2,714 to a salary of £50,270. If thresholds rise at that rate and the extra salary is paid at 20% tax, you will pay £543 more next year. But if the threshold is frozen, you'll pay £1086. To you, that's double, but the same cash rise applies to everybody earning above that level.

Scotland's higher rate is higher, at 41 pence in the pound, arguably to pay a little more for better or more generous public services and to load tax more on to higher earners. But let's leave that debate for another day.

And also to avoid over-complicating things, let's leave aside the anomaly that earnings between £43,663 and £50,270 face deduction of the higher level of National Insurance Contributions at an all-UK level of 12 pence in the pound. It falls to 2p above that level.

To focus instead on the gap in threshold: that is because the Scottish government chose to freeze that level while it was raised for the rest of the UK. That also demonstrates how fiscal drag works.

John Swinney will publish the draft budget at Holyrood on 15 December.

If you pay tax in Scotland and earn £50,270, you pay £2,709 on the tranche of income between the higher rate threshold in Scotland and the one in the rest of the UK. If that tranche of income were taxed at the Scottish "intermediate rate" of 21%, you would instead be paying £1,387.

These illustrations consider the higher rate thresholds going up at the the most recently published average rate of pay inflation. But if it went up at the average rate of consumer price inflation, as it currently stands, your £43,662 pay and the threshold would be going up not by 5.4% and £2,358 but by 10.1% or £4,410.

Fiscal drag - the effect of frozen thresholds is most obvious at that point at which the tax rate rises most steeply. But it affects everyone who pays income tax.

If your pay is £12,570, you'll pay no income tax this year. But if that threshold is frozen, and your pay goes up by the average 5.4% or £679, then next year you will be paying £129 tax in Scotland, and £136 in the rest of the UK.

That applies to everyone who earns above that level. So a higher earner gets the effect of fiscal drag at every threshold that's frozen.

That's how it affects the individual earner and tax payer. How does it affect government income? A lot.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has looked at the effect of fiscal drag on (non-Scottish) rates and thresholds of tax, and existing plans (ahead of Jeremy Hunt's statement on Thursday) to freeze thresholds for four years.

It says that existing government plans to freeze the personal allowance (which applies throughout the UK) until 2025-26, will mean 1.4m people will have been been drawn into paying income tax by then, taking the total number of income tax payers to 35.4m.

By 2025-26, the freeze will be costing basic-rate taxpayers £500 per year (in today's prices).

The four-year freeze to the higher-rate (rest of the UK) threshold means that, by 2025-26, 7.7 million people will be paying higher-rate tax. That's 14% of adults and 1.6 million more than the figure today, where 11% are paying higher rate.

Together with the freeze to the personal allowance, freezing the higher rate will cost most higher-rate taxpayers around £3,000 per year, in today's prices.

An additional rate of tax is paid, at 45% in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and at 46% in Scotland, by those earning more than £150,000 per year. That threshold has been frozen since 2010. So by 2025-26, there are projected to be three times as many additional-rate income tax payers as there were when the additional rate was introduced - up from 240,000 to around 600,000 now, to 760,000.

How much does that threshold freeze raise in tax? When it was announced in spring of last year, it was forecast to raise £8bn in the fourth year. When it was applied to tax bills last year, the Office for Budget Responsibility thought it could raise £18bn by the fourth year.

With inflation at much higher levels than foreseen, meaning more people and more earnings being drawn into the effect of fiscal drag, the Institute of Fiscal Studies thinks the boost from frozen thresholds and allowances could be £30bn.

And we're now seeing speculation that the freeze could be extended beyond 2025-26. We won't know how it will apply in Scotland, at least until the draft budget is published at Holyrood on 15 December.

Below the political radar

Fiscal drag also applies to Land and Buildings Transactions Tax. The thresholds did not change as valuations went up, so tax take went up with them. Tax revenue from that in Scotland rose from £416m in 2015-16 to more than £600m only four years later. And valuations have risen steeply since Covid.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission has estimated that it will rise from £518m in 2020-21 to £987m by 2027-28.

The other side of this calculation is the freeze in benefits, or the threshold at which benefits are withdrawn, for child benefit for instance.

If these are frozen, the government stands to make very large savings. By limiting the working age benefits increase to 3.1% earlier this year, while inflation was rising to much higher levels, it is already doing so.

Freezing benefits brings less of the political backlash that ministers could face from actually cutting welfare payments, just as freezing tax thresholds brings much less political pain than raising rates.

They tend to go below the political radar. That's why they're called stealth taxes.

- Published13 November 2022