Our increasingly unhealthy economy

- Published

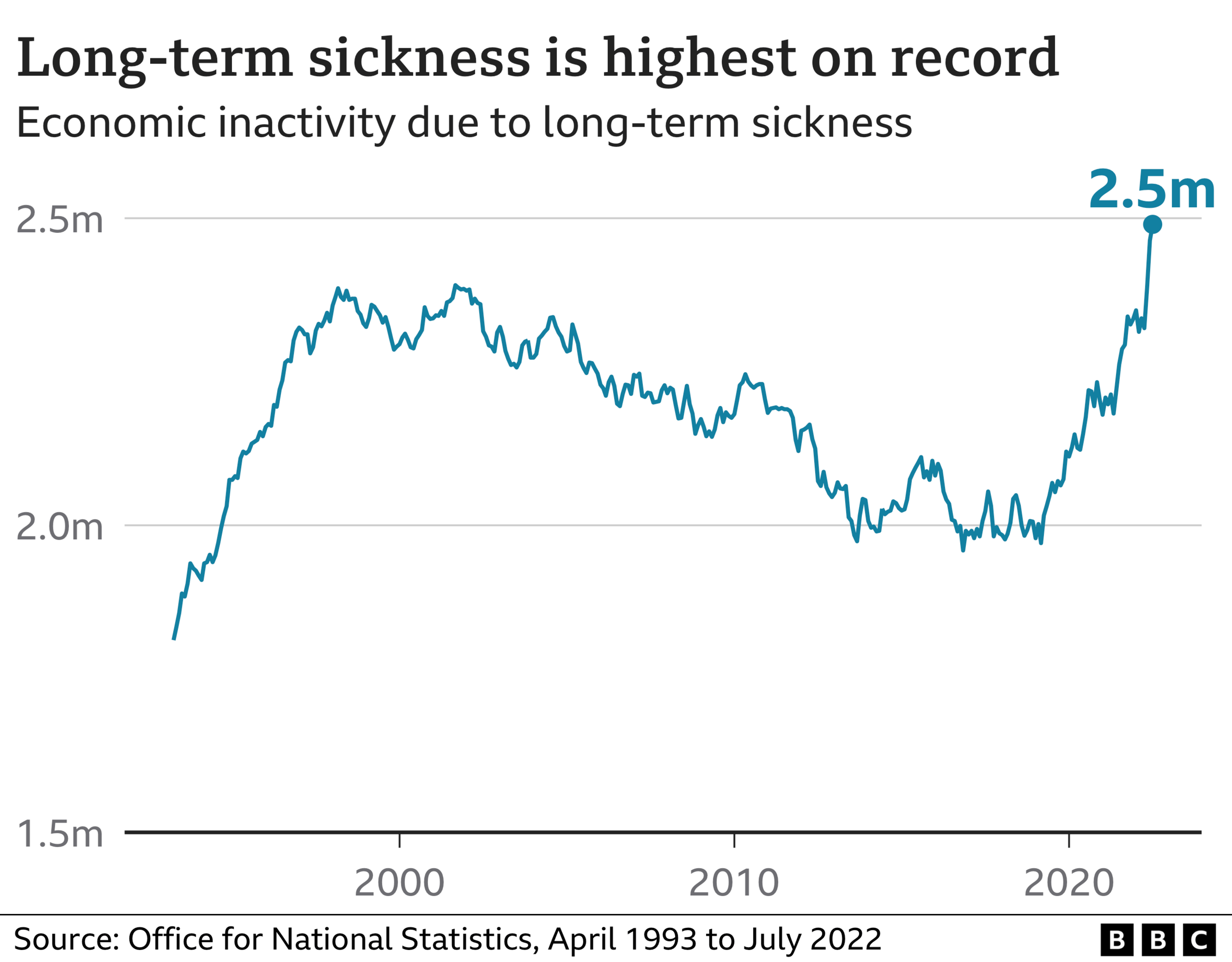

The number of people out of work due to long-term illness has been soaring but it's not as simple as saying this is all due to the pandemic. The increase began before that.

Older age groups are much more likely to be affected by long-term illness, but among younger people the problem has been rising more steeply and it has a lot to do with mental health.

Government is being challenged to tackle the challenge of people who want to work but can't and businesses are being urged to make a priority of a healthy workforce.

Could the nation's dodgy health and creaking health system be linked to its economic problems?

These two are often discussed in isolation from each other. But it has become clear that the rising number of people who are out of the labour market and suffering from long-term illness is having an impact.

The evidence from the latest official data confirms the pattern. Since 2009, the number of people across the UK who are long-term sick has risen from 2 million to more than 2.5 million.

In the ONS's figures for Scotland the evidence isn't quite so stark, but it's still there.

The number of people classified as "economically inactive" and giving the reason as long-term illness was below 200,000 in 2018. In each of the past four quarters, it has been above 240,000.

There is a problem with long Covid and with NHS waiting lists as the health service struggles to recover from the demands put on it by the pandemic.

But as with the UK figures, it's not quite that simple.

The figures were low in 2018 and beginning to rise in 2019, before Covid struck. From 2019, as the UK total has risen from 2 million to 2.5 million, 360,000 of those were added after the pandemic began.

The ONS had a deeper dive into its own UK-wide figures in a recent report and it muddied the waters further.

Yes, it said there's clearly an issue about the rising number of people citing long-term illness as the cause of being absent from the labour market.

But no, it's not just about the pandemic.

Those citing "mental health and nervous disorders" rose by 22% between 2019 and this year. Those with back and neck problems rose by more than 60,000, or 31% - and that may be a warning about the risks of so many people doing office work from home.

But then it was the retail and wholesale sector that had many of the worst long-term health problems.

The ONS found a significant number of those with long-term illness had previously given the cause as "looking after a family member", including parenting or looking after older parents.

Long covid is only partly to blame for the rise in people too ill to work

And a significant number who ceased to have long-term illness moved to another reason for not being available for work, including looking after a family member.

What are we to make of that? The ONS tends not to interpret its own numbers, so the interpretation is up to others.

And one of those others is Andy Haldane, former chief economist of the Bank of England and now chief executive of the Royal Society of Arts.

He delivered a strong message to the Health Foundation last week, which emphasised that the economy should not be seen in isolation from the rest of society.

It is within "a tightly-coupled set of complex sub-systems", including financial, social, community and health relationships.

A society is "only as strong as its weakest sub-system", Haldane said.

A healthier population can be linked to economic growth over the past three centuries.

But the lack of resilience now within UK health and healthcare contributes to a "weak and weakening societal immune system".

The number of economically inactive people has been increasing since 2019

It's no coincidence, he suggested, that life expectancy has taken a dip, and healthy life expectancy - the age the average person reaches before ill-health reduces the quality of life - has become more of a factor.

The picture is clearly aligned with deprivation. Poorer people die younger, and have shorter healthy lives, and that trend is clear with each tenth of the population.

The problems set in early and need to be addressed at childhood, yet Haldane listed the ways in which public services for children are being depleted.

In Scotland, there is a response to that, with the Scottish Child Payment - this week rising to £25 per week and extended from nursery level to children up to 16 years of age - covering about 400,000 young people.

That is seen by poverty campaigners as a very important step in the direction of tackling those issues.

While older groups seem to be, predictably, more vulnerable to physical ailments that keep them from working, the bigger growth rate is in younger age groups.

Between spring 2019 and spring of this year, the number classified as "long term ill" in the ONS numbers were up 29% for those aged 16 to 24, and by 42% for those aged between 25 and 34.

That took them to 14% of all those in the category of long-term illness, and of them more than 60% were men.

Mental health

Mental health appears to be a key element of this.

Haldane highlights that as a reason for being unable to work given by 50% more people aged 16 to 24 than was the case in 2006. It's true of young women, but again, there's more of a rise among young men.

The Resolution Foundation has found the number of young men in that category across the UK rose from 18,400 in 2006 to 27,400 last year.

All this raises questions of how well the NHS is set up to meet the challenge.

Haldane's lecture suggested that simply plugging gaps and hoping to fill vacancies is to ignore the gulf in provision when compared with similar countries.

The UK has long had a highly efficient health system, and people have been very proud of it.

But that efficiency is looking less attractive as its capacity struggles to meet need, demand and expectations.

Time for employers to act

This is a problem for the economy broadly. But it's being recognised also as a problem for business.

While workers are awaiting NHS procedures, some may be off work, and some others may be working at well below their potential.

Haldane argued that the "ESG" mantra of business - environment, social and governance - must have an H added for health.

And the CBI employers' organisation has set out its prospectus for a wellbeing approach.

It calculates that 131 million working days lost to ill health in the UK each year translates to a total cost of £180bn per year.

It sets out a plan that would help industry interventions in the working-age population to reduce levels of ill-health by up to 20% by the end of this decade.

It's launching a UK-wide Work Health Index to benchmark businesses' health provision.

'Urgent action'

Brian McBride, president of the CBI, said: "Labour market resilience is a precondition to growth. Without healthy, productive employees, the UK economy will be unable to achieve the growth it sorely needs.

"Businesses understand the link between health and wealth, and have a major role to play.

"While the NHS continues to serve us all in our moments of immediate need, employers across the UK have a golden window emerging from the pandemic to lean into long-term measures which enhance employee health and wellbeing.

"With the UK staring down a fiscally constrained period, the moment to boost the UK's preventative health model is now."

At the Health Foundation in London, policy manager Sharlene McGhee says that employers have a big role: "Businesses should focus on keeping people with ill-health in employment, maintaining contact with workers on sick leave and making adjustments to ensure their working environment is accessible".

She said one in four of those counted as economically inactive due to long-term illness were actively wanting or trying to get back to work, and the pressure to do so was increased by the squeeze on their household budgets.

But it's about a lot more than employers, she added: "The government must recognise the drivers and scale of the recent rise in economic inactivity. This cannot be achieved by solely focusing on the unemployed.

"People out of the labour market should be a priority. Without urgent action to support people with ill health back into work, long-term sickness is at risk of having an enduring impact on the national economy."

Related topics

- Published14 November 2022

- Published15 November 2022

- Published12 October 2022

- Published11 October 2022