Brexit: The scorecard two years on

- Published

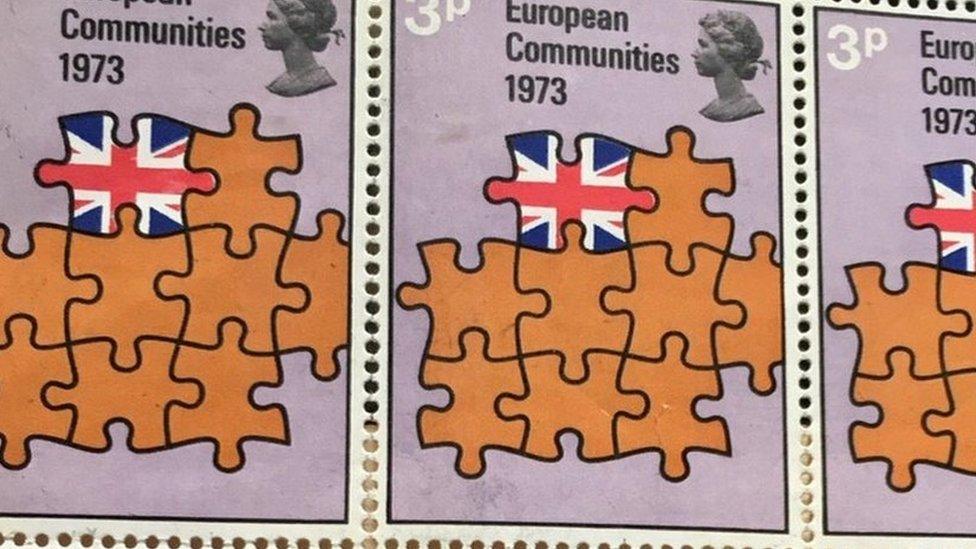

Britain joined the European Communities in 1973

It is 50 years since Britain joined the European Economic Community, and two years since it exited the single market. As the Covid effect fades, it is a bit easier to see the Brexit effect.

The report card on Brexit is not reassuring, either on growth, inflation, business costs or on the impact across economic growth or productivity. Some companies are gaining from Brexit, where they can substitute for EU firms that are no longer willing to export to the UK.

Trade links with Northern Ireland remain uncertain and unresolved, while a battle looms over the stripping of legacy EU laws from British legislation.

It is 50 years to the day since the UK joined the European Economic Community. It is two years since Britain exited the European single market.

The UK has been trying to find its way through Brexit for longer than it was fighting the Second World War, but with rather less sense of direction or national mission.

So how is it going? In economic terms, the past year has helped differentiate the impact of Covid from the impact of Brexit.

Doing so has exposed a hefty price being paid by many firms, as well as public service employment, for dislocation of Britain from its nearest neighbour's trading bloc.

A newer complication has been the impact of war in Ukraine, which takes a lot of the blame for inflation taking off.

Brexit has helped push up prices though. With a tighter labour market, firms have struggled to get the staff they need, helping to push up wages.

And companies have seen their capacity reduced. In hospitality, for instance, hotels are restricting room vacancies because they can't get housekeeping staff. Restaurants cannot open as many days as owners want because there aren't the staff for kitchens or waiting tables.

The hospitality industry has been hit by staff shortages

Firms complain they cannot get the imported goods and components that used to be supplied seamlessly from the continent. Or if they can, it is at a higher cost.

One Scottish retailer recently told me that a German supplier refuses to supply in small quantities because of the paperwork involved, so the Scottish company has to import in larger quantities meaning higher stock levels at higher cost.

An engineering firm has had to substitute components from a European supplier, with some from the US and some from the UK, both at higher cost.

That import substitution effect was one of the more predictable benefits of Brexit from a British perspective. Instead of importing goods, they're sourced more locally.

That is a trend we have seen elsewhere in the past three years because of supply chain disruption sparked by the pandemic slamming the brakes on trade. The US is seeing "reshoring" of manufacturing from Asia, after years of offshoring.

But that comes at a cost. The reason they were sourced from foreign manufacturers was because trade allowed for companies and consumers to source from the most efficient producers, or to seek out the best quality. Obstacles to trade have the reverse effect.

Blessed cheesemakers

A year ago, my TV report on the first year outside the single market and customs union looked at three Scottish companies that were finding it harder to sell into Europe or to recruit from Europe.

It provoked a complaint that I had failed to cover the upside for some firms. After a long process, the complaint was upheld by the BBC's executive complaints unit.

This year, however, I can provide balance, of a sort. Some exporters have learned to handle the paperwork and absorb the extra costs, such as Scotland's salmon farmers.

Scotland's salmon industry appears to have adapted to Brexit

And I have heard of a company reporting a Brexit dividend. Highland Fine Cheeses in Tain is gaining from the difficulty that Britain's delis are finding in importing cheese from the continent.

As you'll probably recall, Liz Truss, some years before her astonishing 44 days as prime minister, thought it "a disgrace" that Britain was importing so much cheese.

She therefore ought to be delighted that a Highland cheesemaker is gaining by filling the display cabinets of up-market delis with Caboc and its "minger" where French and Italian cheeses used to be.

The British government has issued a new year message about the gains to be had from the trade deal struck with Australia. It cites Isle of Harris Gin as one company that hopes to gain from the removal of a 5% tariff on imported spirits.

It has less to say about the outrage from Scottish hill-farmers, who foresee the gradual removal, over 15 years, of obstacles to UK importing of industrial-scale Australian lamb as undermining the finely-balanced financial case for farming sheep on "less favoured" Scottish hillsides.

Low investment

So, having seen a forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility that Brexit would mean the economy lost 4% of its output, below the level it would have been operating, the evidence is supporting that.

While inflation mostly imported from global energy prices is making us worse off and at a rapid rate, the Brexit effect on making Britain worse off remains partially hidden.

Much of the evidence emphasises trade's recovery post-pandemic, but modelling across countries without the Brexit effect shows recovery at a much faster pace.

Compared with other major economies, also hit by inflation, Britain's current downturn looks more severe. And it may not just be the direct economic effects of Brexit, but the longer-term discouraging effect on investment from protracted political instability.

The Centre for Economic Performance reckons that including that "dynamic" effect of Brexit could increase its impact on potential output to a hit of between between 6.3% and 9.5%, and the Centre for European Reform suggests the impact may have been a shortfall by up to 11% of the output that might have been expected.

That itself is connected to the political fallouts from Brexit, largely within the Conservative Party.

That low investment contributes to a hit to productivity of around 3% below the levels that would be reached otherwise, according to the Bank of England, which also highlights the impact on inflation from the weaker pound in six and a half years since the referendum.

One scorecard on the first two years that is worth noting is the British Chamber of Commerce. Its membership is wide-ranging and includes those who enthused for Brexit back at the 2016 referendum.

Drawing on the evidence of 600 members, it looks back on year two of Brexit seeing more rules introduced for UK exporters to the EU, with more paperwork and cost.

While many firms don't export and are unaffected by Brexit, more than three quarters (77%) of firms for whom the trade deal of two years ago is applicable say it is not helping them increase sales or grow their business.

Some 56% of firms face difficulties adapting to the new rules for trading goods.

Almost half (45%) face difficulties adapting to the new rules for trading services, and a similar number (44%) report difficulties obtaining visas for staff. So the problems are far from universal, but they are widespread.

Businesses have had to adapt to new trade rules

The British Chambers quote an unnamed retailer in Dundee: "Leaving the EU made us uncompetitive with our EU customers. We would have lost all of our EU trade without a base in the EU. This has cost our business a huge amount of money which could have been invested in the UK had it not been for Brexit."

From a retailer in Ayrshire: "Customs on both sides of the EU border seem to have a separate set of rules to be able to charge different amounts for the same thing. We don't know until it's too late what these costs are."

And from a manufacturer in Dorset: "Brexit has been the biggest ever imposition of bureaucracy on business. Simple importing of parts to fix broken machines or raw materials from the EU have become a major time-consuming nightmare for small businesses, and Brexit related logistics delays are a massive cost when machines are stood waiting for parts.

"We used to export lesser amounts to the EU, but the bureaucracy makes it no longer worthwhile."

Brexiteer agenda

And the British government's response? It's on the case:

"The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (struck on Christmas Eve two years ago) is the world's largest zero tariff, zero quota free trade deal. It secures the UK market access across key service sectors and opens new opportunities for UK businesses across the globe.

"Despite difficult global economic headwinds, UK-EU trade is rebounding, with recent data showing that UK trade to both EU and non-EU countries is above pre-COVID levels."

So it's economic growth, but there are other factors holding back.

The government spokesman goes on: "The UK has provided exporters with practical support on the implementation of the TCA, including launching an ambitious Export Strategy and a new Export Support Service".

There is a claim of trade deals with 71 non-EU countries are mainly rolling over terms they had previously agreed with the EU. Australia and New Zealand are exceptions, but have been criticised, even by George Eustace, the agriculture secretary in place when they were signed, for giving too much away and being bad for Britain.

The thorniest problem of the Brexit trade deal is in Northern Ireland, where it has led to suspension of the Assembly. Four British prime ministers have struggled and failed to square that circle. The impasse continues, and there's no sign of the European Union giving concessions.

There are new rules coming in for state aid, and a replacement for European structural funds, for which big claims are made. But then, according to the Scottish government, the latter falls far short of full replacement, and they are being deployed to get round devolved institutions.

Several changes have been put further on hold, including the introduction of a new UK product testing regime and import checks on EU goods coming into the UK, giving EU exporters an advantage over UK rivals.

In 2023, expect to hear a lot more about the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill. At the end of this year, it is intended to strip thousands of EU laws out of British legislation, to fulfil the Brexiteer agenda of deregulation.

But it has business groups nervous about unintended consequences, it could hit consumer rights, while trade unions see it as undermining workers rights and there are environmental protections that campaign groups will fight to keep.

A year ago, included in my TV report on Brexit, a wise observation from Sir Anton Muscatelli, economist and principal of Glasgow University, was that we may have to wait several years until the political heat goes out of Brexit.

Then, we can have a hard-headed look at how to build a new relationship with the European Union that repairs some of the damage and works for both sides. That reckoning still seems some way off.

- Published22 December 2022

- Published2 December 2022

- Published30 November 2022

- Published1 December 2022