Salmon firms struggle against current

- Published

A large Norway-based producer of farmed salmon says campaigning against the industry is making Scotland an increasingly difficult and uncompetitive location for growth

New restrictions planned for west coast salmon cages are fuelling an unusually high level of tension between industry and regulators

Norway's parliament has just agreed that the tax rate on the industry should be more than doubled, as have Faroe Islanders, while Chile shares with Scotland controversy over marine protected zones

More than 50,000 people were estimated to be participating in protests against the impact of highly protected marine zones.

Along a coastline of remote communities dependent on jobs in fish-farming, the government has been under pressure to pull back on its plans to protect biodiversity.

International campaigners for the oceans are watching closely, wanting to protect pristine coastlines, and pushing for further protection zones.

A sign of things to come in Scotland, perhaps? Perhaps.

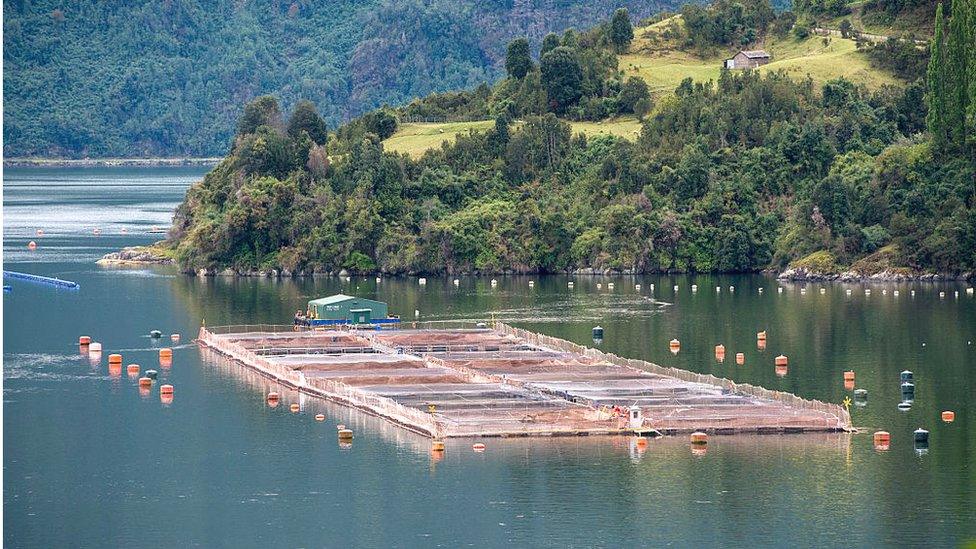

But for now, this is being reported by Intrafish trade website, external from Chile, with nearly 4,000 miles of coastline and last year the world's second largest producer of farmed Atlantic salmon.

Chile is the world's second largest producer of farmed Atlantic salmon

Meanwhile, the world's biggest salmon producer, Norway, with around half of global output, has a different controversy raging - a new tax on the industry's profits, at more than double the previous rate, to ensure that the public get a fair share from use of their seabed.

Norway, which exported £7.6bn worth of salmon last year, is where most of the worldwide salmon farming industry is owned and controlled. The plan was to slap a 40% super-tax on profits in addition to the country's standard 22% corporation tax, backdated to January.

The government in Oslo did a deal with other parties on condition that the hike is scaled back to 25% super-tax, and that a larger share of it is handed to municipal and county councils in the coastal communities where the value is generated.

In the Faroes, the past month has seen agreement that tax on revenue will go up from 5% to as much as 20%, depending on the cost of production and prevailing market prices.

What about the world's third biggest producer of salmon?

Scotland, producing up to 200,000 tonnes per year, or less than a seventh of Norway's output, has seen a recovery from the disruption of Covid. It has learned to live better, though not too happily, with the friction of exports by truck to the European Union.

First quarter exports to Asia were well ahead of last year, as fresh premium Scottish farmed salmon are air-freighted in the bellies of reinstated long-haul passenger flights and served to post-pandemic diners in China.

There is no discussion, yet, of higher tax on the industry. But the bill for leasing seabed from Crown Estates Scotland has recently doubled from around £5m per year to £10m. That money is passed on to the Scottish government. Salmon Scotland, representing the industry, wants to see it used to improve housing in coastal communities where its workers are being priced out.

Salmon vies with bakery and chocolate to be Britain's biggest food export. Last year it re-established that status in the wake of Brexit and pandemic disruption.

Lochaber is where salmon farming began more than 50 years ago. This is a Scottish success story. But its share of world production has been slipping as growth is constrained by regulation, and it's far from being a happy ship.

BBC Scotland broke the news this week that the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Sepa) has plans to introduce new restrictions on the industry, to reduce harm to wild salmon.

A lot of the plan, which is under consultation, external until 15 September, is to limit the allowable level of sea lice.

These parasites gather in sea cages and attach themselves to salmon, multiplying at speed where there is such a ready food source .They stunt the growth of fish, which then require early harvesting. Following that, their cages have to be left fallow.

Those opposed to fish farming say it is cruel to fish, with high mortality rates and use of chemicals to combat the lice. Hopes of farming and deploying wrasse fish as a natural predator for lice has not come to much in reality.

Those wishing to protect wild, migratory salmon (often the same people) say that high concentrations of lice around fish farms are one reason salmon runs have depleted in recent decades.

It's one of several reasons, and one which is being controlled, claims the industry, pointing to east coast salmon rivers that are effectively dead, but without any nearby fish farms to blame.

Industry anger

There is real industry anger at the latest move by Sepa, briefing the BBC before telling fish farmers, and getting their proposals out there just before industry leaders were due to meet the new ministerial team responsible for charting a course for the industry.

That course was being guided by the report commissioned by ministers from business fixer and Dumfriesshire-based troubleshooter Russel Griggs.

He concluded last year that action was required to streamline regulation of the industry, and within 12 months. We're still waiting, and while we do so, Sepa is seen as moving into animal welfare territory that's for others.

Why the delay? Well, this is difficult politically - with dogged campaigning against the environmental impact of the industry, with Scottish Green ministers, and with the SNP representing coastal communities where fish farming jobs matter.

It may be because of the hiatus of party and government leadership, and disagreement between ministers. Under Humza Yousaf's leadership and ministerial team, Mairi Gougeon retains responsibility for aquaculture. But that rural affairs brief intersects with the environmental role in the cabinet now held by rising SNP star Màiri McAllan.

With Green MSPs having secured a promise to introduce Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs), it is McAllan who has the task of squaring that pledge with strong coastal and business opposition to the plans. She also has oversight of the Sea Lice Risk Framework.

The fish farming industry is concerned that she brings more cabinet clout to the role and significantly less support for the industry than Ms Gougeon.

Sepa says it has engaged with the sector on the sea lice risk management framework and advised the consultation would be published on Tuesday.

'Mistrust, dislike and vitriol'

The broader factor identified by Prof Griggs was, in his words, that he had never seen the level of "mistrust, dislike, and vitriol at both an institutional and personal level between the industry (mainly finfish), certain regulators, parts of the Scottish government and other stakeholders".

He continued: "There are those in the industry who believe officials within some regulators and government bodies have on occasion been actively briefing and supplying information against the industry to those that would seek to close it down completely."

Sources in the industry still claim there are officials running an agenda to squeeze the life out of fish farming in Scotland, and the environmental agenda within the Holyrood government is content to see that happen.

Fish farm tanks

At SalMar, the second largest of Norway's salmon-farming giants and co-owner of Scottish Sea Farms, one of the biggest producers, particularly in Shetland, recently warned that opposition to the industry is keeping it caged in its pen, at the same time that the Scottish government says it wants to increase production.

Its annual report reflected a very difficult year for "biological challenges", meaning sea lice and disease, and also for political challenges.

"Framework conditions for salmon farming in Scotland have remained relatively constant over several years," it said. "The growing influence of special interests (Non-Government Organisations, organised anglers, etc) has led to more challenging regulations than in Norway, which has in turn contributed to a higher level of costs (lower efficiency, less economies of scale)".

SalMar is even more harsh about its home country's new tax, saying this week that it is "based on the incorrect assumption that aquaculture food production is a location-bound resource rent industry that consistently generates extraordinary returns disproportionate to the risk involved".

The tax vote this week, following a five hour debate in the Oslo parliament, or Storting, "will have a significant distorting effect. The high tax level and the unfavourable design of the new tax will withdraw a substantial portion of investment capital from the industry".

You'll recall the same thing being said about the UK's windfall taxes on oil and gas production, and on power generators.

English farmed salmon

This remains a highly dynamic sector, with some change forced on it by regulation; some by those "biological challenges", and some by developments in the way and the places fish are farmed.

The Faroes is growing its influence and scale, as a producer and the base for Bakkafrost. There, too, there is consideration of a resource tax.

Iceland is a newcomer to the industry, with a long coastline that's well suited to salmon cages, and climate change meaning its chilled waters may hold better prospects than Scotland's.

SalMar has partnered with Norwegian engineering giant Aker to develop much stronger cages designed to withstand wild conditions out at sea. Moving out from sea lochs is also seen as a long-term prospect for Scotland's salmon farmers, allowing currents and tides to disperse the concentrated environmental impact of caged fish.

The other big development has been by Scottish Sea Farms at Barcaldine, north of Oban, and by Bakkafrost, under construction at Applecross in Wester Ross, and now in planning at the former Hunterston coal yard in Ayrshire.

They're building much bigger onshore tanks for smolts (small salmon). The idea is that they can be grown for longer in controlled conditions and put out to sea pens at a later stage, cutting their exposure until they're more robust.

That reduces the risk of sea lice and disease while at sea. Less time for each fish in sea cages will allow companies to increase production, as they are currently limited to 2,500 tonnes on each licensed site.

Since 2019, the £58m Barcaldine facility has cut the time spent at sea by two months, with a plan to extend that further and cut it by five months. The lifespan of a farmed salmon is between 12 and 28 months.

Onshore salmon farming is being developed worldwide, and could undercut sea cage farming.

It requires a lot of expensive infrastructure, and creates a lot of wastewater.

But now, England is entering the salmon farming industry. There is a plan for a vast shed covering 50 water tanks, costing £75m and producing 5,000 tonnes of salmon per year, at the old Humberside trawler port of Grimsby.

- Published31 May 2023

- Published29 June 2023

- Published11 February 2022

- Published26 April 2021