Housing emergency: Why has it happened and what can be done?

- Published

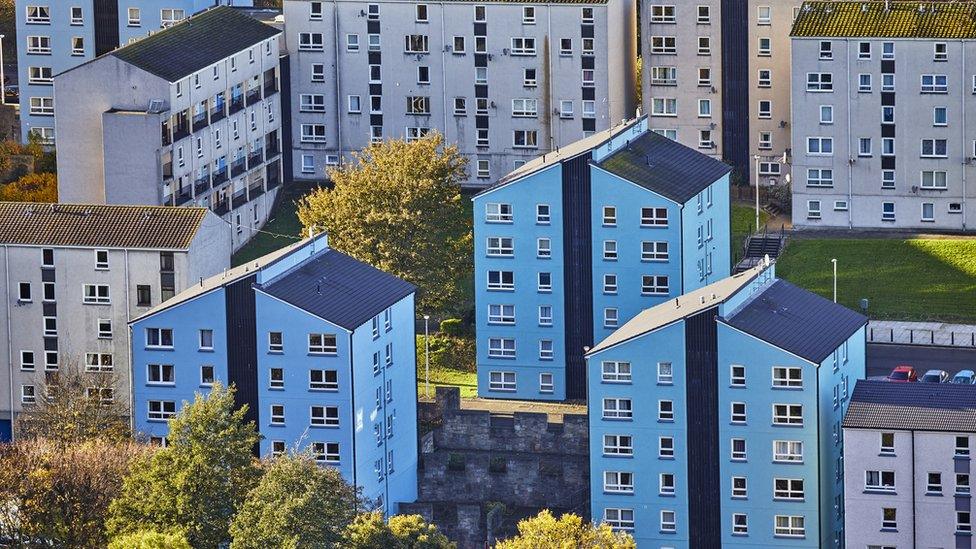

A housing emergency in Edinburgh, following one declared in Argyll and Bute, reflects deep-rooted pressures in the system, which extend across Scotland.

Social housing has been sold off, and new building is a long way from replacing it to meet demand.

There is no simple or quick answer, but there are gains from bringing vacant homes back into use, longer-term requirements to boost housebuilding, and policy changes that will or could shift the way the housing market works.

Whatever else it means to declare an 'emergency', it is a signal that expectations and obligations are not being met, and things cannot go on as they are.

City of Edinburgh Council has done so, to draw attention to the pressures it is under, to make a special case to the Scottish government for more support and to galvanise the capital's public and private sector into a plan of action.

It is the second local authority in Scotland to take this step. Argyll and Bute did so in June. The urgency of the emergency is not so clear from the apparent pace of change since then. The Lochgilphead administration launched an opinion survey last month, and it is to have a 'summit' this month.

The two councils face some housing problems in common, but also contrasting ones. Argyll's are based around the rural economy and its appeal to those who want a second home, or to own a holiday let. That has pushed up prices for ownership and for rent, in a county which does not have high earnings.

Short-term lets are a challenge in Argyll and Bute

Getting hold of land for development can be a problem where landowners are reluctant to co-operate. And with its population ageing faster than others, there's the challenge of ensuring public services are sustained with housing for essential workers.

Edinburgh's housing problems have a lot to do with its success, in attracting people to live and work there, drawing in investors, a very large number of students and also tourists. Short-term lets are a challenge for Argyll and Edinburgh more than most others, where AirBnB landlords have turned so many homes into visitor accommodation.

And one answer to Edinburgh's pressures has been the outward growth of Greater Edinburgh. Scotland's fastest-growing communities are around the capital, in the Lothians and Fife. The recent initial census figures showed Midlothian's population rising by 16% in a decade.

There are many other problems and causes of the housing emergency that Edinburgh and Argyll share with the rest of the country, but where they are more acute is in those council areas. Here are some.

Feelgood factor

Council house sales, starting in the 1980s, allowed tenants to buy the homes they rented, at reduced cost. That was seen by some as hugely successful, in giving people a stake in their homes, more security than they had as tenants and an asset base. More widely, it stripped a large number of properties out of the reach of those who rent, and often the best quality ones.

Since then, councils and housing associations have struggled to meet demand with new building and refurbishments. The number of those who look to them for social housing - broadly speaking, below market prices - far outstrips the number of homes available.

That is the main cause of homelessness, where Edinburgh is housing 5000 households in temporary accommodation, and there are 200 applications for the average social tenancy.

Since the 'right-to-buy' boom put home ownership into the heart of public policy, cementing the peculiarly British obsession with owning bricks and mortar, government action has been focussed less on social housing and more on helping people onto the housing ladder and ensuring people stay on it.

Edinburgh city council declared an emergency on Thursday

Light touch regulation of mortgage borrowing was a political choice fuelling a feelgood factor for those whose homes were gaining in value faster than they could earn the same money. That bubble led to the bank bust of 2008. It became far more difficult to get a mortgage after that, but banks and government agreed to avoid the pain of previous property crashes, and did what they could to avoid repossessions.

Rather than the market correcting with some harsh falls, as they did in other countries, house prices stabilised. And so home owners stayed aboard the property express, taking advantage of very low borrowing costs. That made it all the more attractive to buy-to-let. (You can watch recent BBC documentaries for more.)

Those pressures brought a sharp increase in the size of the private rented sector. It nearly doubled in Scotland, to more than 15% of all households, while home ownership as a proportion dropped to just above 60% of Scottish homes, and young people grew up to be defined as Generation Rent.

Precarious margins

Those privately rented properties have replaced social rented housing as having the biggest problems with quality and energy efficiency. To curb rent increases as price inflation took off last year, the Scottish government froze rents for six months and it has since capped increases at 3% per year, with permanent rent controls now the subject of consultation.

A legal challenge to the rent controls, which was brought by the private landlords, including rural estates, led on Thursday to a judgement in favour of the Scottish government.

The rent freeze does not apply to new tenancies. So landlords use the opportunity of new tenancy contracts to raise rent in anticipation of future rent controls. And new contracts are often required when one person in a shared flat leaves and another comes in. There's more explanation in the Disclosure investigation for BBC Scotland.

There was sharp increase in the size of the private rented sector

That is where we have reached. And unless you're sitting in your own unmortgaged property, which has continued to build in market value, then a lot of it looks like a sorry mess.

As usual, it is worst for those at the precarious margins, who are unable to get the housing they need. Housing benefits are vital for many, but insufficient to solve the problem. Those people's problems are connected to the wider private market - to a private rented sector in which rents for new tenancies are rising faster than any other part of the UK.

And the growth of private rentals is connected to the scale of demand outstripping supply of homes to own in the capital, which continues to push up prices, far beyond the starter flats and into every part of the market.

Financial distress

It doesn't have to be this way. While some will urge more radical action, the more conventional policy responses start with bringing vacant properties back into use. That's where there are relatively quick gains. The campaigning charity Shelter Scotland has led the way, and urges every council to have an officer with the job of extending that. But while it's a help to bring 900 homes back into use within one year, that's a long way from being the only solution required.

Allied to that could be changes to the structure of the market, which could meet resistance: Forcing the sale of vacant properties and restricting the purchase of second and holiday homes. New powers are on the way that would allow councils to do some of that through increased council tax.

The pressure on Edinburgh housing due to the use of so many homes for short-term visitor lets may ease under the legislation requiring licensing which was introduced at the start of October. In Edinburgh, those who cannot get planning permission for a change of use to letting will have to drop out of that market.

A further response can be rent controls, but measures taken so far appear to have had unintended and unwelcome consequences in pulling investment out of the market, reducing the number of private homes available for rent and the addition of new-build homes.

There are rising numbers of short-term lets

The longer term responses include a bigger commitment of the Scottish government's capital spending. While saying there is £3.5bn committed to building 110,000 homes by 2032, it seems clear that has not yet proven sufficient to meet the need.

And there is a risk that much of that housing budget could be diverted into the pressing need to improve the energy efficiency of existing homes - costing many billions of pounds without increasing the capacity of the housing stock.

With capital budgets tightly constrained, much of the policy answer depends on housebuilders. They can be incentivised - indirectly so when government finds funds to share equity with first time buyers. They can be required to provide a share of each new development as 'affordable housing', for rent or sale at below market rates.

But there are further measures that could be required of housebuilders who build up landbanks, and build on that land at a time when it aligns with their bottom line interest in maximising profit.

Those profits are hit when prices decline, when construction supply costs rise, as they have done steeply, and when construction workers are scarce or getting more expensive. So the supply pipeline of new private housing, with associated affordable units, gets constrained by those housebuilder choices. Even the sector's own trade body says there's a need for more competition, having lost many smaller construction firms since the 2008 crash.

Being susceptible to boom and bust, construction has recently returned to the top of the list of sectors with companies at risk from financial distress.

Intervening in that market, or doing more to re-shape the market for private ownership or private rental, is towards the radical end of solutions.

But Edinburgh city council's declaration of an emergency is a signal that such solutions could, and arguably should, be up for consideration.

- Published2 November 2023

- Published9 October 2023

- Published29 September 2023