Following the leader

- Published

- comments

Quietly and without fuss in the Echo Arena here in Liverpool, Labour has implemented an internal reform which will resonate in Scottish politics.

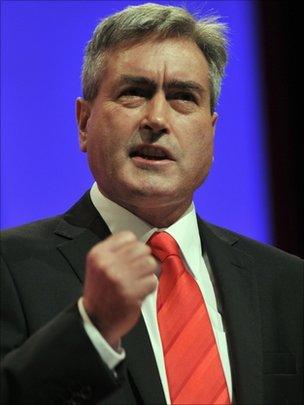

Iain Gray took responsibility for the outcome of the last Scottish election

The switch forms just one part of a series of changes designed by Ed Miliband to modernise the party he leads.

Delegates to the Labour Conference were informed this morning that the reforms were endorsed en bloc, with 93% in favour.

And the change for Scotland? That there should be an elected leader for the Scottish Labour Party.

More to come - but that is the core of today's change.

What's that? You thought they already had an elected leader? You thought that was Iain Gray, soon to be replaced?

Think again. Mr Gray led the party's group at Holyrood. He did not lead the overall party in Scotland. His successor will.

I well recall the hustings meetings prior to Mr Gray's election.

One of his opponents, Andy Kerr, argued then that the contest should properly be for the elected leader of the entire party in Scotland. He wanted structural reform.

At the time, Mr Gray's argument was that the post would evolve: that the very fact of an election by the wider party would confer additional status upon the post, whatever the formal constraints.

That happened to some degree - but not to the extent of establishing Mr Gray as the full leader of the party, including the MPs.

He remained, primarily, the Holyrood leader - with, inevitably, something of a fissure between the party groups in the Scottish and UK parliaments.

Will the change close that fissure? Of itself, no. Will the change enhance Labour's standing with the Scottish electorate? Of itself, no.

Indeed, the document endorsed in this morning's declared vote recognises that fact when it notes that structures do not win elections.

However, the document also trumpets the reform as "the biggest change for 90 years", marking "a fresh start for the Scottish Labour Party".

That is, frankly, going it some - although one can understand the determination of the party to talk up their prospects given the scope of the defeat at the Holyrood elections in May: now regularly referred to as "the gubbing".

To be clear, all that the Labour conference in Liverpool has done is agree that the election of a Scottish leader is a matter for . . . Scotland.

It is called devolution and, as Labour acknowledges, should have happened years ago.

The detailed rules will now be drawn up by the party in Scotland and will go for ratification to a specially convened conference of that Scottish party.

But it has already signalled that MPs and MEPs will be allowed to contest the leadership, alongside MSPs, with the caveat that they would subsequently have to seek a seat in the Scottish Parliament.

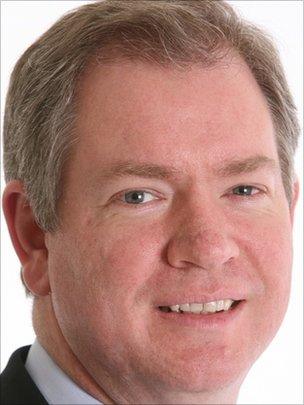

That has meant the current potential contenders for the Scottish leadership include MP Tom Harris together with MSPs Johann Lamont and Ken Macintosh.

All three are here in Liverpool, assiduously cajoling.

Tom Harris, who is an MP, has declared for the leadership of the Scottish party

There will be practical change too for the new leader: control of resources and party direction.

As Iain Gray notes in his conference speech today, it will involve "responsibility for our own capacity and strategy".

Mr Gray also places the party reforms in the context of the "terrible" result in May, for which he takes responsibility.

He argues the delay in implementing party change in Scotland added to Labour's perception problems, noting: "Over time our lack of party devolution undermined our capacity to convince Scottish voters of our aspirations for a better Scotland and our determination to deliver for them."

Today's change, along with comparable reforms already implemented by the Tories, mean that the centre of political gravity, in Scottish terms, has defaulted still further towards Holyrood.

Is that good news for the SNP - playing upon the field where they are dominant? Or a challenge to their hegemony in the zone of Scottish patriotism?

Plainly, Scottish Labour hopes it can achieve the latter - which explains an interesting section in the speech drafted by Ann McKechin, the shadow Scottish secretary.

She depicts the Nationalists as obsessed with "our separate history and culture, be it Bannocburn or Culloden".

By contrast, she argues, Labour derives its core from a more recent history, one held in common with England or supported by English people: votes for women, the NHS, trades unions, UCS.

The snag for Labour is that the SNP may prove stubbornly resistant to the attempt to corral them into past conflict and to remove them from solidarity with the working people of Scotland.

Still, it is fascinating to witness once more a conflict over history, recent and more remote, as Labour - in a quiet, understated way - catches up with the consequences of political history in Scotland.