Minister in combative mood

- Published

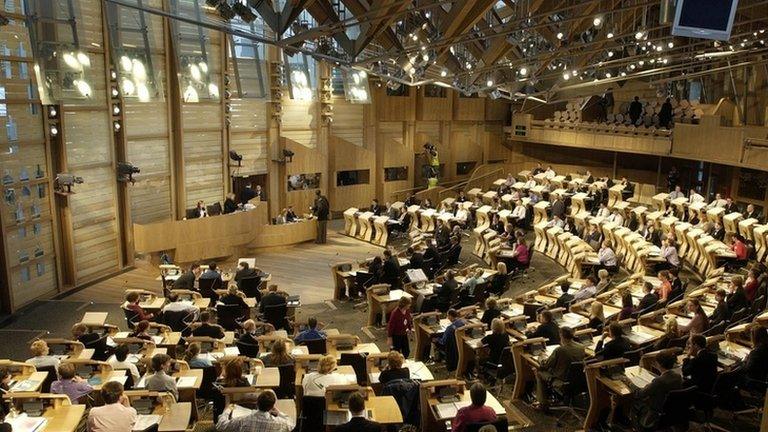

Finance Secretary John Swinney turned on Labour's Ken Macintosh during the budget debate

John Swinney's demeanour is customarily modest and restrained. Mostly, he presented his spending plans for 2013/14 in that fashion - reflecting, no doubt, the wider, grim economic environment.

But there is fire there too, real fire. And it flashed into flame when he turned upon Labour's Ken Macintosh who had accused the Finance Secretary of a "pass the buck" budget.

He treated the comment with withering contempt and derision, arguing that the roots of the current economic crisis lay during Labour's period in office and that they were allied with the Tories in seeking to hold Scotland back (from the objective of independence).

In sum, Labour accused Mr Swinney of slashing jobs. The Minister asked, in effect: "Just what would you do?"

Cash terms

Although he phrased it a little more elegantly - and stressed such factors as the living wage for government employees and the promise of no compulsory redundancies in the public sector.

That exchange told a story about the tension of office, the economic climate - and the underlying competing narrative of these times. Which is - just who is to be held responsible for gloom and cuts?

For cuts there were, in real terms overall and in cash terms for some individual budget lines.

Mr Swinney appeared sensitive too, entirely understandably, to the criticisms which have come his way since last year when he announced his over-arching spending plans for the period up to 2015.

And so he went out of his way to praise the economic and social contributions of the colleges - after complaints about cuts and a well-run counter campaign. And he stressed new capital investment in the housing sector - after a comparable previous row.

In essence, there was a threefold narrative from Mr Swinney. He argued that, within limits.....

he was attempting to drive growth

that his stewardship of devolved economic powers was better than the Chancellor's control of the broader financial levers

and that, consequently, independence would strengthen Scotland's prospects.

Local authorities have negotiated a budget settlement which protects their funds in cash terms (once the money transferred to the new central police and fire authorities is accounted for.)

But challenges lie ahead. Employers complain that the council money is only sustained by an increase in business rates - scarcely, they argue, conducive to growing the economy.

And then there's public sector pay. After a two year freeze for all but the lowest paid, it is to rise by one per cent next year for those 28,000 employees directly under Mr Swinney's sway - most civil servants, NHS managers and quango staff - except those earning more than £80k.

But it seems certain that local authority staff - far more numerous - will seek at the very least to emulate that rise. Unions say one per cent is miserly - but also question whether there is money available in the budget to fund even that, without cutting services.

Mr Swinney did not attempt to disguise that this was anything other than a tight budget.

It will undoubtedly prompt umpteen detailed questions as the various lines of spending are scrutinised.

But, right now, three fundamental questions. Will the capital investment help to generate growth - or are the global conditions simply too negative?

With a thaw in the pay freeze, will restraint vanish altogether - and what might that mean for the budget settlement?

And, politically, who will take the hit if the economy continues to suffer?

- Published20 September 2012

- Published20 September 2012