Scottish independence: How do you write a constitution?

- Published

Written constitutions embody rights and duties

First Minister Alex Salmond has reiterated his desire for Scotland to have a written constitution, if the country votes to become independent in 2014. He wants to embed social and economic rights such as the right to a home and free education. But how does a new country write a constitution?

The UK is in a club of one in the European Union. Of the 27 countries in the EU all but one have a single, binding constitutional document outlining the limits of government power. Just three countries in the world have never written a formal constitution - the UK is one of them.

Writing a constitution might conjure up images of 18th Century events such as the American Constitutional Convention, but it is still a key piece of modern state-building.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the removal of old colonial structures across Africa have meant, in the past 25 years, there have been about 21 countries which have become independent, sovereign territories.

The UK's uncodified system has evolved over the past 300 years. It says that parliament, representing the people, is not bound by other laws or statutes. It is a flexible system which has survived partly because the UK has evolved without a great constitutional crisis to bring matters to a head.

For newly-formed countries - without their own democratic traditions - those relationships between government and the people, between the courts and citizens' rights, for creating a political community and resolving civic disputes, all have to be mapped out.

Some constitutions include specific policies, like America enshrining the right to free speech.

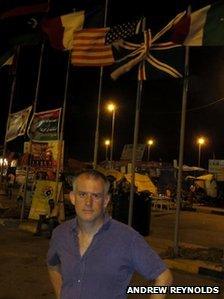

Prof Andrew Reynolds was in Libya in 2011 to advise the new government

Others embody principles, such as "equality" or "freedom" which require ongoing interpretation.

Prof Louis Aucoin has hands on experience helping developing democracies. He was UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon's deputy special representative in Liberia, and helped Kosovo draft its constitutional settlement.

He says those 200-year old models have one key flaw - they were composed of elites. New nation-building has to be inclusive.

According to Prof Aucoin, much of the work is done before writing a single word.

He says: "Drafting actually to me is something which should happen after you've had a full debate about the issues.

"In many cases the way in which this has been done is that a constitutional commission is appointed from the beginning which is charged with the task of doing the civic education and also conducting the popular consultation."

The University of Chicago's Prof Tom Ginsburg, who has advised constitutional bodies around the world, said there were various ways the public could be involved.

He said: "You could have the public elect a constituent assembly, like happened in Iceland, or you could have a political body like a parliament draft the constitution while it's doing other jobs too.

"You can have an expert committee do the first draft. You can have a referendum at the end to approve the product."

New democracies

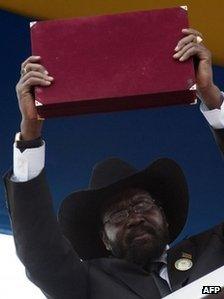

South Sudan's president Salva Kiir holds up a copy of its constitution

That process of gathering, consulting, meeting and drafting could expose long-term political or ethnic tensions, but according to the experts a spirit of consensus and compromise is usually apparent. Countries borrow heavily from their governmental traditions when looking for a way forward.

In Sudan, after decades of conflict with the North, it was the ballot box which secured independence for South Sudan in 2011. It is the world's newest country. It offered almost a blank slate in terms of the system and structure of its government.

According to Prof Andrew Reynolds, who is another hands-on expert and helped the South Sudanese draft their constitution, all countries "base themselves on what they've done before, even if it wasn't very useful".

He said: "For village elections, the candidates would stand at the front and supporters would line up behind their candidate, and the longest line won. That's what the SPLM (Sudan People's Liberation Movement) wanted to use in South Sudan for the (national) elections."

But the dominance of the one party, and the lack of democratic traditions, has become a problem for the country.

"In the South Sudanese parliament you have 120 MPs, 117 of which are SPLM government members. Because they wrote the constitution by themselves."

Prof Reynolds was also one of the first advisors on the ground in Libya after the rebels took control of the country during the Arab Spring.

He wanted to ensure that minorities were fully involved in the process of forming a new democracy, so he met women's groups.

He said: "The younger women all were wearing the hijab, looked very Libyan to me, and when they spoke, they spoke with Glaswegian accents. Or they were from Bristol or from London or from Boston.

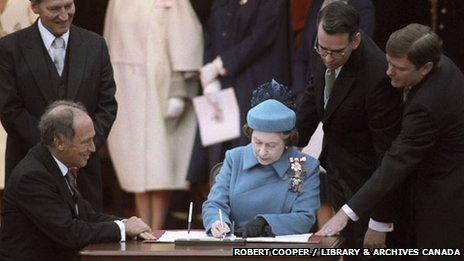

The Queen signs the Canadian constitution in April 1982

"They all had been incredibly well educated overseas and they were coming back to Libya to try to help their country change. And there was a lot of optimism in that room, there was a lot of innovative thinking about how you get women involved in both local and national government."

But that dynamism was eventually lost as the old power dynamics in Libyan society pushed back. Prof Reynolds now describes that process as a missed opportunity. Women have been largely shut out politically.

With all this expertise at hand, how can such a seemingly undemocratic outcome be tolerated?

Prof Aucoin said: "The central ethical issue here is that experts have to be careful to make sure that they confine their role to being a resource, without trying to manipulate the process.

"You have to never forget that the right to make the ultimate choice in this case in this local right."

Long lasting settlement

According to research carried out by Prof Ginsburg, the average constitution lasts just 19 years. To form a long-lasting, robust settlement, new constitutions can not be carved in tablets of stone.

Not every issue can be solved at the one time, but by allowing issues to be revisited further down the line, the governing can begin.

The success or failure of a constitution seems to rely on whether the public take the text to heart and feel the document embodies their relationship with their country. It also sees the document as continually evolving, and not rules set in stone.

As Prof Aucoin puts it, "the process of constitution-making is a continuing conversation with the public".

According to Prof Ginsburg: "Although there's increasing agreement on the contents and the form of constitutions.

"There are as many ways to write constitutions are there are countries."