Minimum alcohol pricing: The frontline in the battle over booze

- Published

The BBC has learned that five European wine-producing nations are trying to block Scotland's plans for a minimum price for alcohol. The BBC's Scotland correspondent James Cook has been to Portugal to find out why.

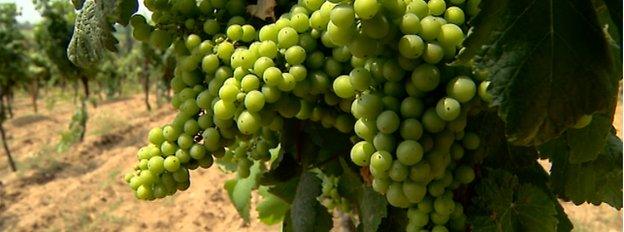

Deep in the heart of Portugal's Bairrada region, the lush green grapes are swelling slowly in the summer sun.

It is a tranquil scene but this is the frontline in the battle over booze.

Supporters of minimum pricing say strife is being sown in these sleepy vineyards.

They want dearer wine, beer and spirits to cut crime and save lives in Scotland.

That worries Luis Pato, who fears profits from higher prices will go to retailers, such as supermarkets and off-licences, but a drop in sales will be his problem.

Mr Pato has been making wine in the valley since 1980; his family since at least the 18th Century.

Luis Pato says he does not want to see exports to Scotland stall

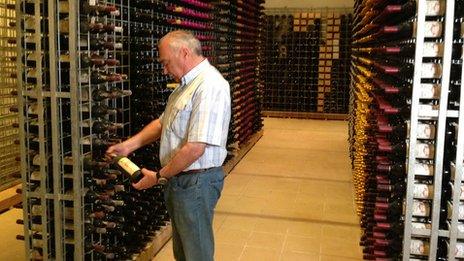

Dapper and moustachioed, he stands in his cellar at Quinta do Ribeirinho, waving a large glass of red as he talks.

"The export market is crucial," he says. "I export 70% to 20 different countries.

"Scotland is a good market for my wines because you like wines with structure, maybe for the cold during the winter!"

Mr Pato's cellars do not look like the home of cheap plonk but he insists that budget wines are important to him.

"The entry-level spreads the image of the brand, the name of the brand for more people," he explains.

For that reason, he claims, minimum pricing would be bad news.

"It's very bad for us as you can imagine because we are starting to sell better and better in the Scottish market."

The winemaker is also worried about the precedent the policy would set.

"We have globalisation and you are destroying the free market," he says, adding wryly: "This is strange for me but I am an old guy."

Traditional methods

Further south, in the town of Lousã in the Coimbra region, Daniel Redondo's family has been distilling the aromatic liquor Beirão for more than a century.

The recipe has been in the family since 1910 or earlier, when it was sold as a medicine in the town's pharmacy.

When alcoholic medicines were outlawed in Portugal around 1920, Mr Redondo's enterprising grandfather decided to continue selling the sweet liquor for pleasure alone.

Beirão, explains the grandson, is made from a double distillation of aromatic plants and spices from around the world.

In the distillery the air is rich with the smell of herbs and spirit.

The Redondos employ more than 80 people to produce their liquor

The business is relatively small; producing up to 20,000 bottles a day, the output constrained by the tradition of manually tying a ribbon around every bottle.

The Redondos employ 52 staff at the production and bottling plant with 30 more around Portugal dealing with marketing and sales.

Mr Redondo says he is struggling to break into the British market and frets that minimum pricing would be a "big barrier", making the task even more difficult.

"I believe that the established brands will get their own space and then the retailers would focus on the low-cost brands... and we are in-between, we are not a low-cost product and we are not an established brand in the UK," he explains.

He also questions the claim that minimum pricing would help reduce drinking, saying "there is no direct relationship between price and consumption".

Mr Redondo contrasts northern European countries with "very high taxes" on alcohol where consumption is high, with southern nations such as his.

He says: "I believe that Portugal is a good example that we can have a spirit, we can have a wine without any harmful drinking problems related to that."

Binge drinking

The only examples of binge drinking in Portugal are when the British come on holiday, he says, with an apologetic smile.

"If the price was the problem you would go to Scandinavian countries and they would be OK and they are not," he adds.

"I believe they tolerate binge drinking much more than we do so that's a cultural problem, that's not a tax issue."

Mr Redondo says the solution is education, not restriction.

That's a view shared by Mario Moniz-Barreto, secretary general of the Portuguese Spirits Association.

The Scottish plans are a "worrying precedent," he says.

If price was the problem, he argues, then Portugal would have more difficulties with alcohol than Scotland.

"We don't see a harmful use of alcohol... in fact we see the opposite," Mr Moniz-Barreto says.

"We have some of the lowest percentages of binge drinking, we have some of the lower percentages of drunkenness... so the answer is not in introducing more legislation... the answer lies in liberalisation and education.

"At a time when every country needs to export its way out of recession and out of the fear of crisis it's more important than ever not to create artificial and ineffective measures.

"We have a saying in Portuguese... which is 'the forbidden fruit is always the most desired one'."

Mr Moniz-Barreto, immaculately tailored and with perfect English, speaks gently but his message is serious.

"In Portugal over the past few decades we have been swamped with Scottish products," he says.

"It's now our turn to try to export some of our products to Scotland and I'm sure the national spirits industry of Scotland would not be appreciative of trade barriers being imposed by the Portuguese government."

This appears to be a softly-spoken threat from a tranquil valley: Scotland and its whisky industry might be risking a trade war if minimum pricing goes ahead.

- Published25 July 2013

- Published25 July 2013