Margo MacDonald: The life and times of a political 'blonde bombshell'

- Published

Margo MacDonald's political career saw her elected to both the UK and Scottish Parliaments

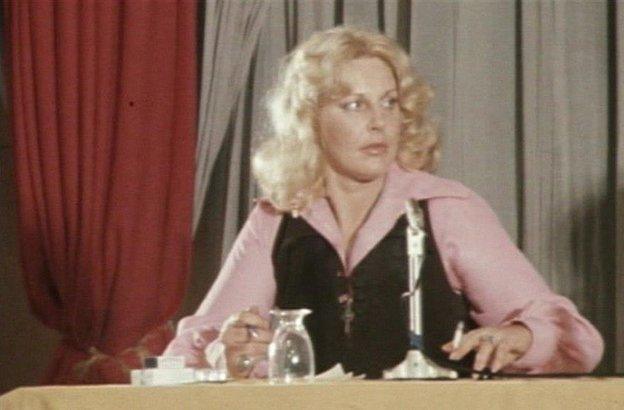

It's easy to see why Margo MacDonald was known as the "blonde bombshell".

From the moment she burst on to the scene with the SNP in the 70s to her bitter bust-up with the party and reinvention as a popular independent politician, she never relinquished her role as a political firebrand and maverick operator.

Serious yet charismatic, Ms MacDonald was hugely influential within the Scottish independence movement for more than 40 years.

She was also known for high-profile campaigns, from protecting female sex workers to legalising assisted suicide for the terminally ill - an issue which took on a deeply personal significance.

Margo - easily identifiable by her first name alone - came to national attention with a stunning 1973 by-election victory for the Scottish National Party in Glasgow Govan, which was previously a Labour stronghold.

Frontline politics

She declared: "I'm the MP for Govan - can we get that straight first of all." However, she would spend just 112 days in the job before being ousted at the subsequent UK election.

Undeterred, Ms MacDonald served as the SNP's deputy leader during the Nationalist Westminster honeymoon of the 1970s, before quitting the party in the internal conflict which followed defeat in 1979.

The one-time PE teacher and Hibernian fan, born and educated in Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, went on to build a career as a respected broadcaster, working on topical and current affairs programmes.

But the pull of elected politics was strong, and Ms MacDonald eventually rejoined the SNP alongside her second husband Jim Sillars, who had also won Govan for the party after a by-election in 1988.

Margo MacDonald burst on to the political scene with a stunning win in the 1973 Glasgow Govan by-election

The rebirth of the Scottish Parliament in 1999 brought Ms MacDonald back to frontline politics as an MSP.

Scotland seemed happy to see her - but was the SNP?

As the party gathered for its first post-devolution conference, Ms MacDonald urged it not to sacrifice the goal of independence for Blairite-style modernisation, saying: "I am absolutely certain that some nationalists have lost the plot, not all of them I am glad to say."

It set the scene for a series of brushes with the SNP, which included getting a written warning from party chiefs in June 2000 for missing a parliamentary vote without permission and briefing a newspaper, against party policy.

During the SNP's "civil war", in the early 2000s, Ms MacDonald appeared to aim for a pragmatic approach, opining: "There have been turmoils in the past and usually the party has reasserted what it saw as the mixed bag of personalities that it wanted to lead it, and I think that will happen again."

On the campaign front, Ms MacDonald fought hard on issues like health care.

She was also one of the most vocal critics of the Holyrood building project fiasco. Her search for the "smoking trowel" eventually led to the Fraser Inquiry, which examined why the building was completed three years late and at 10 times its original estimated cost.

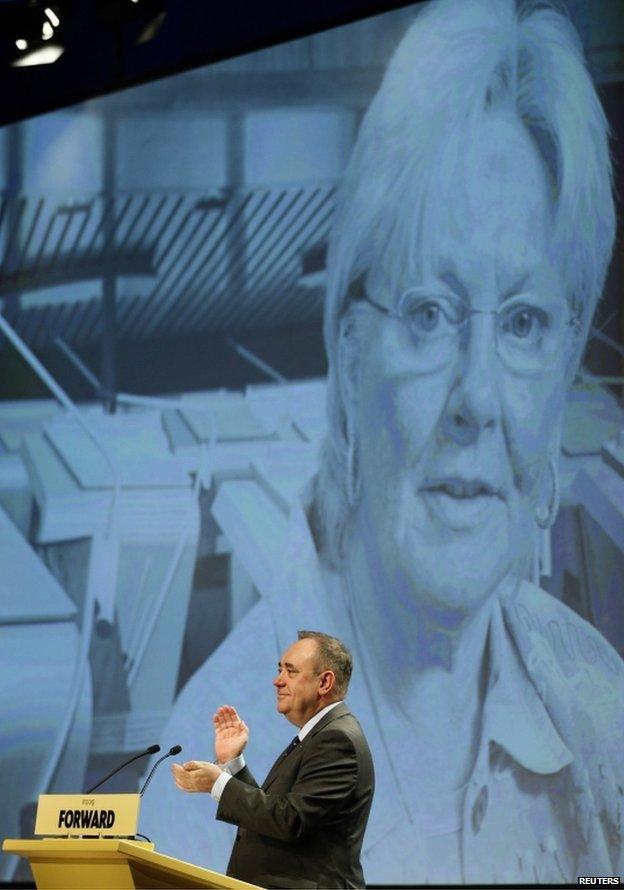

SNP leader Alex Salmond led a tribute to Ms MacDonald at the SNP spring conference

On hearing that inquiry chairman Lord Fraser would have the power to name and shame those who did not give evidence, she remarked: "The problem is, some of the folk he might name have no shame."

In the end, Lord Fraser concluded there was no clear "villain of the piece", and when a later report said civil servants should not face disciplinary action Ms MacDonald said: "It looks as though anything short of grand larceny is okay."

She also took on the controversial issue of prostitution, introducing a bill to legalise prostitute "tolerance zones".

The move was prompted after a long-running experiment, operating in Edinburgh's Leith area and judged to have been a success, was scrapped after complaints from residents - although welfare workers said the move had led to an increase in attacks on prostitutes.

The chances of Ms MacDonald's legislation making it through parliament were slim, but it did prompt a debate and she eventually withdrew the bill after saying Scottish ministers were taking action to look at the issue.

Ms MacDonald was a deeply serious, yet charismatic campaigner

But when it came to party politics, her strife with the SNP was never far from the surface.

Relations reached a new low in April 2002, when then leader John Swinney expressed disappointment after Ms MacDonald described far-right French politician Jean-Marie Le Pen as "intellectually robust" in a newspaper article.

Ms MacDonald - who had previously interviewed the former French National Front leader as a TV journalist - said she was not fascist or racist, and was merely attempting to analyse the French presidential elections.

The episode prompted suggestions the SNP was trying to discredit her - speculation Ms MacDonald said was later proven by the decision to drop her ranking on the Scottish Parliament's Lothian regional list from first to fifth place, giving her virtually no chance of re-election in 2003.

Following her decision not to stand for the SNP, Alex Salmond, a backbench MP at the time, said Ms MacDonald found the concept of party loyalty "difficult".

"Margo will enjoy her day in the limelight, Margo likes nothing more than a camera stuck in her face - not that that's a bad thing for a politician," the future Scottish first minister said at the time.

Mr Salmond's later return to the SNP leadership, on a joint ticket with Nicola Sturgeon, did not convince Ms MacDonald.

"You don't join a party because of Alex Salmond's blue eyes or Nicola's personality," she said at the time - although the SNP would go on to win their first term in office a few years later.

In July 2002 Ms MacDonald confirmed she had been living with Parkinson's Disease for seven years, but blamed political "forces of darkness" for her condition being leaked to the media.

As the SNP denied being the source of the disclosure, several senior party activists quit their posts in protest.

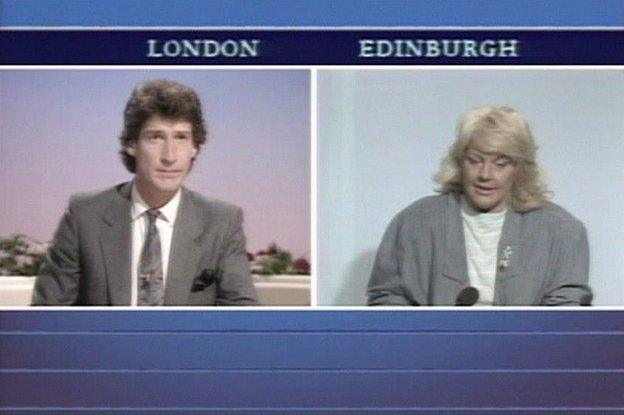

Ms MacDonald embarked on a successful broadcasting career between stints as an elected politician

At the start of 2003, Ms MacDonald raised concern she was being "expelled" from the SNP without a fair trial, after announcing her decision to stand as an independent candidate in the Holyrood election that May.

Party bosses, who saw things differently, wrote to her saying it considered the move a "public resignation".

Ms MacDonald defiantly told a media conference in Edinburgh: "I paid my membership last month, so I'll be looking for a rebate."

The view from senior SNP figures at the time was that Ms MacDonald had made her own membership untenable, but Alex Neil, a long-time ally on the left of the party, described the end of her association with the nationalists as a loss.

"Every party and every political system should be big enough to accept that you will get people who have a particular individual contribution to make," the future Scottish health secretary said at the time.

Come election night, it was revenge for Ms MacDonald as she swept to third place on the Lothian regional list after winning more than 27,000 second votes.

Elected to Holyrood as part of a rainbow alliance of other independents and smaller parties, she declared: "There is a new force in our politics now."

It was a success Ms MacDonald repeated at subsequent elections.

She launched her 2007 election campaign - typically - on Friday the 13th, with a call for extra capital status funding for Edinburgh.

Issuing her plea to voters while clutching a large picture of a rabbit's foot, she said: "Since I'm as old as Methuselah, voters think I will always be there.

"If they want me to get in, I would ask them to vote for me - just to make sure."

Margo continued to attend parliament, despite her health

Ms MacDonald later got the then minority SNP government to back her funding request, after she agreed to support its budget.

And voters again endorsed her in 2011, despite the massive voting squeeze which delivered the SNP its historic landslide victory.

In parliament, one of Ms MacDonald's highest profile campaigns was her drive to legalise assisted suicide for the terminally ill.

In a memorable speech at Holyrood in March 2008, and with the physical symptoms of Parkinson's disease growing ever visible, Ms MacDonald told fellow politicians she wanted the right to end her own life.

"I don't want to burden any doctor. I don't want to burden any friend or family member," she told MSPs.

"I want to find a way in which I can take the decision to end my life in case I'm unlucky enough to have the worst form of Parkinson's near the end of life."

Her bill to give terminally ill people the right to choose when to die was rejected by a free vote of parliament.

But it was a cause Ms MacDonald pursued right until the end, at the same time as spearheading an attempt to bring the HMS Edinburgh - a decommissioned warship - back to Edinburgh as a tourist attraction.

And that was typical of the varying issues she chose to back, be it a campaign to ban vuvuzelas at Scottish football grounds or joining anti-trident demonstrators in the Scottish Parliament.

Ultimately Margo MacDonald fought, and triumphed, as a party of one.

It was perhaps the only party that could ever hold her.

- Published5 April 2014