A brief history of Alex Salmond

- Published

As Scottish first minister and leader of the Scottish National Party, Alex Salmond has been the most high-profile figure in the independence movement.

He took the SNP closer to its central aim than it had ever been, but after the "No" vote in September's referendum Mr Salmond decided to stand down.

So, how did Mr Salmond go from brash political outsider to international statesman?

In the beginning

Born on Hogmanay 1954 in the ancient burgh of Linlithgow, Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond graduated from St Andrews University and began a career in economics, working for the Scottish Office and the Royal Bank of Scotland.

He also played an increasingly active role in the Scottish National Party, having come to the conclusion that the economic case for independence was strong.

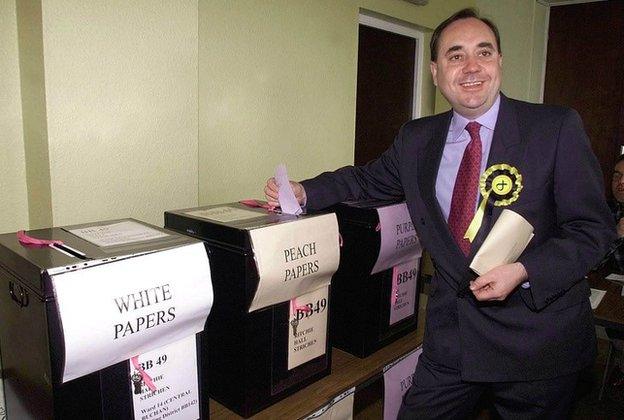

Entry to politics

Mr Salmond's rise to prominence came as the SNP fell on hard times, triggered by Margaret Thatcher's 1979 Conservative election win, which saw the number of Nationalist MPs slashed from 11 to two.

He played a prominent role in the breakaway '79 Group, which sought to sharpen the SNP's message and appeal to dissident Labour voters - a move which earned him a brief expulsion from the party in 1982.

Reflecting on the incident years later, he put it down in part to his being a "brash young man" - although the urge to cause a bit of mischief has never been far from his mind.

Despite this episode, Mr Salmond established himself as a rising star of the SNP, winning the Westminster seat of Banff and Buchan in 1987 - and notably getting himself banned from the Commons chamber for a week after interrupting the chancellor's Budget speech in protest at the introduction of the poll tax in Scotland.

SNP leadership (part one)

When the SNP leadership job came up in 1990, Mr Salmond grabbed the opportunity and, on winning the post, repositioned the party as more socially democratic and pro-European.

Scottish devolution was an opportunity for the SNP. The party failed to win the first Holyrood election in 1999, but gained enough seats to become the main opposition.

During the campaign, Mr Salmond had sparked controversy when he described Nato action in Kosovo as "an act of dubious legality, but, above all, one of unpardonable folly".

After putting in a decade as SNP leader, Mr Salmond decided to quit, standing down as an MSP and returning to Westminster.

During his time in London, Mr Salmond had a visible profile, partly from appearances on TV shows such as Question Time, Have I got News for You and Channel 4's Morning Line, where his horse racing expertise saw him offering tips and insights.

SNP leadership (the sequel)

John Swinney took over the reins as SNP leader from Mr Salmond, but stood down in 2004 following continued criticism from sections of the party and the negative publicity of a leadership challenge.

Many turned to Mr Salmond to grasp the thistle and take his old job back. He responded by quoting Union Army General William Sherman, who, on being asked to run for president following the American Civil War, declared: "If nominated I'll decline. If drafted I'll defer. And if elected I'll resign."

As the leadership contest continued, with Roseanna Cunningham regarded as a front-runner, Mr Salmond made a surprise entry into the race, explaining: "I changed my mind."

Becoming Scotland's boss

Following his leadership comeback, on a joint ticket with deputy Nicola Sturgeon, Mr Salmond led the SNP to what was then its greatest hour - victory at the 2007 Scottish election and delivery of a minority SNP government.

The newly appointed first minister, who returned to Holyrood by winning the Liberal Democrat-held Gordon seat, soon had his first of many brushes with the UK government.

The subject was the future of the convicted Lockerbie bomber Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, who was released by the Scottish government on compassionate grounds on account of his terminal illness, in the face of huge criticism from the US and others.

In contrast, the Glasgow Airport terror attack and the foot and mouth crisis showed how willing the first minister was to work with Westminster on issues of UK importance.

Scottish government policies such as protecting NHS spending, freezing council tax and scrapping bridge tolls and prescription charges were popular with voters.

But critics questioned whether universal benefits were affordable, and accused SNP ministers of giving local authorities a raw deal.

As the global economic meltdown took hold, Mr Salmond blamed "spivs and speculators" for the problems which caused the takeover of HBOS, as the crisis of confidence in the financial sector hit Scotland.

He later faced criticism from political rivals who said HBOS's real problems were caused by the bank's exposure to the volatile mortgage market.

On the day Fred Goodwin was stripped of his knighthood, Mr Salmond also reflected on a letter he previously wrote to the banker when he was running Royal Bank of Scotland, offering the Scottish government's assistance in the takeover of Dutch bank ABN-Amro - the deal which contributed to RBS needing a £45bn bailout.

Looking back, Mr Salmond said very few people could have predicted the meltdown, adding: "If we had the benefit of hindsight we'd do things differently and I am sure that is true of lots and lots of people."

The first minister has faced opposition accusations of close links with big businessmen, including the Stagecoach boss Brian Soutar, US tycoon Donald Trump - who later turned on Mr Salmond over his government's pro-wind farm policy - and media mogul Rupert Murdoch.

Mr Salmond always insisted relations with such figures were about promoting jobs for Scotland.

Conservative dawn

Mr Salmond's hopes of increasing the number of SNP MPs in a hung UK parliament in 2010 with the purpose of "making Westminster dance to a Scottish jig" didn't quite come off.

With a resurgent Tory party on course for victory, Scots voters came out in their droves to back Labour, during a campaign which saw the SNP unsuccessfully take the BBC to court, after it was decided Mr Salmond couldn't debate with Gordon Brown, Nick Clegg and David Cameron on TV.

Despite the result, the first minister came to regard a Tory-led Westminster government as a key argument for independence, by invoking memories of Thatcher (and poking fun at the Conservatives' single Scottish MP).

Breaking the system

It seemed Labour was on course to win the 2011 Scottish election, but Mr Salmond - never to be underestimated - launched into the contest with a positive campaign.

When he came up against Labour's negative, attacking style, Scots voters decided there was no contest - and the SNP was returned with a jaw-dropping landslide win.

Holyrood's part-proportional representation/part-constituency system was essentially designed to keep any one party (ie the SNP) from winning an overall majority - but the nationalists' victory brought about a generational shift in Scottish politics, which had seen Labour as the dominant force for 50 years.

The Salmond Administration V2.0 continued as Scotland's devolved government, pledging to resist Westminster cuts and protect cherished universal benefits, while claiming achievements such as cutting crime to a 30-year low.

Opposition parties regularly argued the first minister was becoming so obsessed with his dream of independence that he'd taken his eye off the ball when it came to Scotland's needs.

Mr Salmond's critics also claimed falling teacher and nursing numbers, and housing shortages, were examples of a lax attitude.

The vote

Mr Salmond didn't bring forward his government's promised Referendum Bill in its first term because it lacked the necessary votes in Holyrood - possibly a blessing in disguise, given the polls were indicating a "No" outcome at the time.

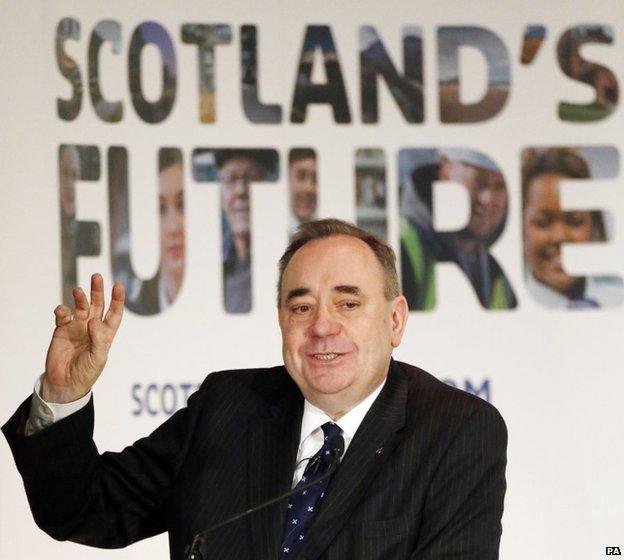

The 2011 election result made the independence referendum a certainty - and it was time for Mr Salmond to put his money (and North Sea oil reserves) where his mouth was.

The first minister, along with his government and the wider independence movement, set out a vision of Scotland's as one of the world's richest small nations - with opponents arguing he was willing to say anything to win a "Yes" vote.

But on the night it wasn't to be, as voters rejected independence by 55% to 45% in the 18 September vote.

The following day, Mr Salmond announced he was standing down as first minister and SNP leader - but not before delivering a warning to his opponents to make good on their promise to increase the powers of the devolved Scottish Parliament.

First defeat

His long-term deputy Nicola Sturgeon replaced Mr Salmond at the top of the SNP in November 2014.

Soon after that Mr Salmond announced he intended to return to Westminster, standing as the SNP candidate for Gordon in the 2015 May election.

He won the seat and was appointed as the SNP's foreign affairs spokesman in the House of Commons.

However, his time at Westminster was cut short by the snap election called by Prime Minister Theresa May for June 2017.

He was the most high-profile of several SNP MPs to lose their seats, suffering his first defeat as a candidate in any parliamentary election since entering Westminster in 1987.

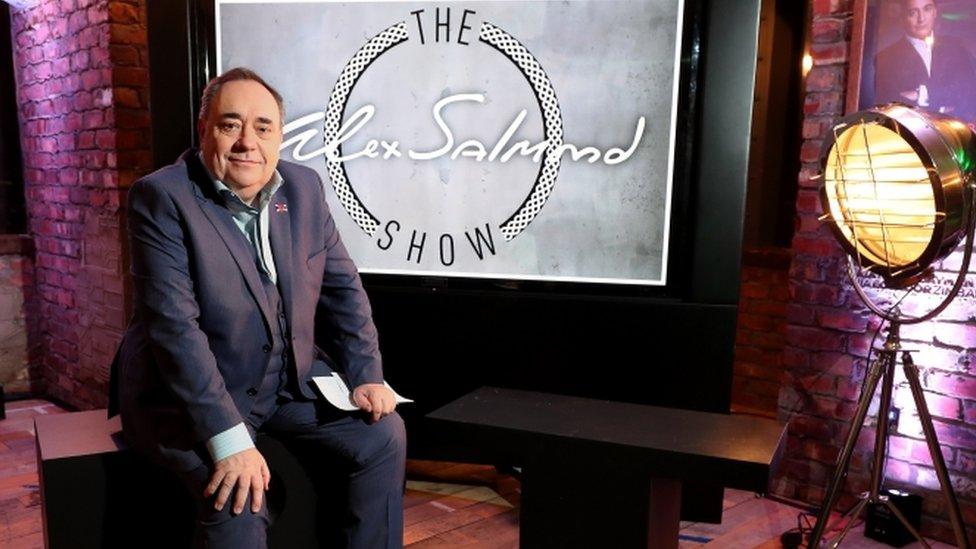

Chat show host

The Alex Salmond Show began broadcasting in November last year

During the summer after he lost his Westminster seat, he hosted a sell-out run of his Alex Salmond Unleashed show at the Edinburgh Fringe, in which he chatted with guests such as Elaine C Smith.

His fortnight at the Fringe was good practice for the TV show he began in November 2017 on the RT channel.

Critics claimed that RT was a Russian propaganda channel but Mr Salmond urged viewers to judge for themselves.

Opponents accused the former Scottish first minister of being a "useful idiot for the Kremlin".

But Mr Salmond insisted that the state-funded channel was not propaganda and he had never been told what to say.

Downtime

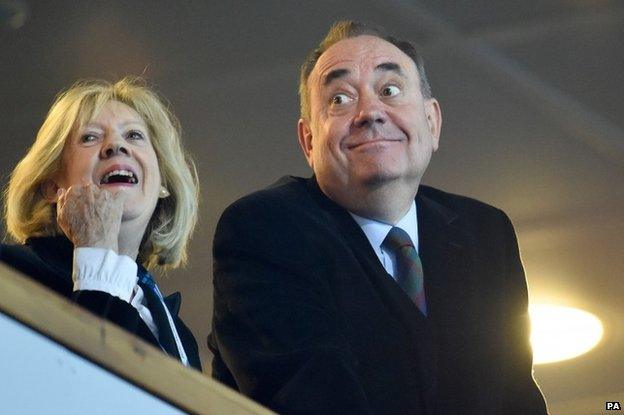

Despite his public profile, Mr Salmond and wife Moira, closely protect their private lives.

He is also known for his fondness for singing, horse racing and (like many Scots) curries.