A brief history of Alistair Darling

- Published

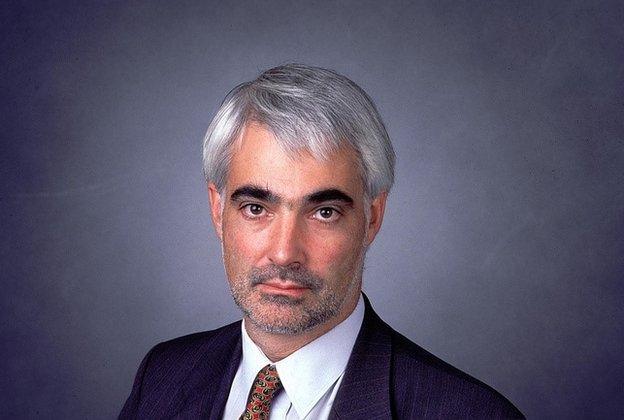

During a near 30-year career in frontline politics, Alistair Darling was almost never known for being outspoken, despite his left-wing student activist days.

He rose from being a "safe pair of hands" Labour minister to greater prominence as chancellor, steering the UK's troubled banks back from the brink.

Now, he faces the challenge of keeping the UK together as the face of the official campaign to retain the Union ahead of Scotland's independence referendum.

In the beginning

Born in London but proudly Scottish, Alistair Darling is himself an example of the very Union he fights to preserve.

He spent his formative years in Edinburgh, attending the city's exclusive Loretto public school, apparently an experience he did not relish.

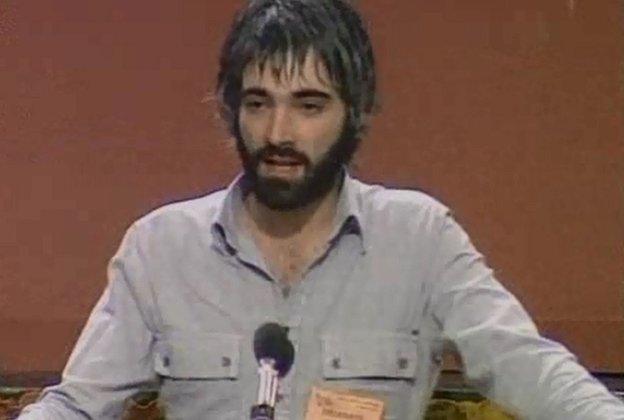

And despite becoming known as a mild-mannered, non-confrontational lawyer, Mr Darling was associated with far-left policies as a student activist in Aberdeen, and reportedly distributed "Marxist" leaflets at railway stations.

He became an advocate in 1984, two years after being elected to the former Lothian Regional Council.

Although anti-devolution in 1979, Mr Darling had become a supporter by the time the second Scottish referendum was under way.

Entry to politics

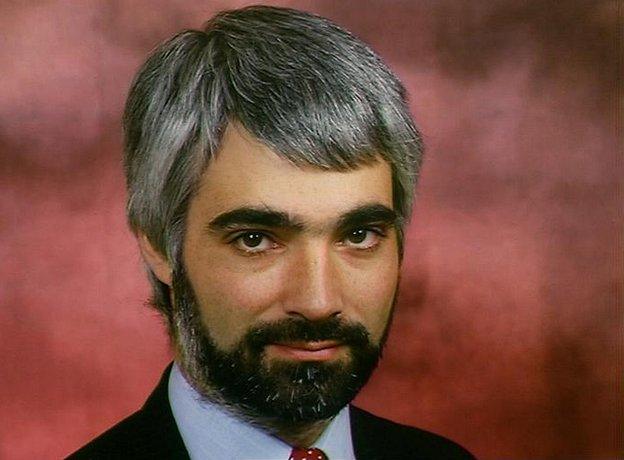

After becoming an MP in 1987, Mr Darling rose quickly through the Labour ranks, becoming closely linked with efforts to modernise the party.

In opposition he served on the front bench in several roles, including as home affairs spokesman.

It seemed Mr Darling had put his left-wing roots behind him, his image transformed from that of firebrand to troubleshooter.

Ahead of the 1997 election, he also toured the boardrooms of the big City firms, to reassure them over Labour's intentions.

However, in his opposition days, Mr Darling was once said to have been mounting a campaign against Rupert Murdoch's predatory pricing policy, but quietly ditched it when told of Tony Blair's bid to charm the media mogul.

He also opposed a proposal by the then Conservative MP Nicholas Budgen to make the Bank of England independent of the government - one of the subsequent Labour government's first acts.

Call to government

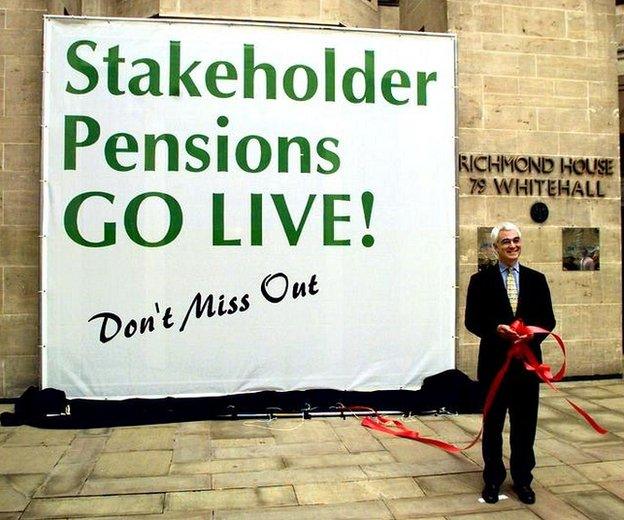

Following Labour's landslide 1997 election win, Mr Darling served as chief secretary to the Treasury, putting in place wide-ranging reforms to financial regulation, after the collapses of Barings and BCCI.

He then replaced Harriet Harman as social security secretary (a job later re-named work and pensions secretary), delivering Labour's welfare reforms and taking responsibility for spending a third of the government's budget.

Mr Darling once said he would like to be remembered as "the minister who began to eradicate poverty", but was targeted by pensioners outraged when their pensions were raised by only 75p.

The episode led to a rebellion at Labour's conference in 2000.

Mr Darling, said to have a knack for mastering complex briefs in record time, was parachuted into another "trouble" job in 2002, when Stephen Byers resigned as transport secretary amid the collapse of Railtrack.

His proposals for road pricing - not universally popular among drivers - sparked fierce debate.

Mr Darling's later comments, while at the Department of Trade and Industry, that Britain's future energy needs may have to be met partly by a return to nuclear power, also raised eyebrows.

But all-in-all he played a canny game, remaining a Tony Blair loyalist, while keeping a foot firmly in Gordon Brown's camp.

Number Eleven

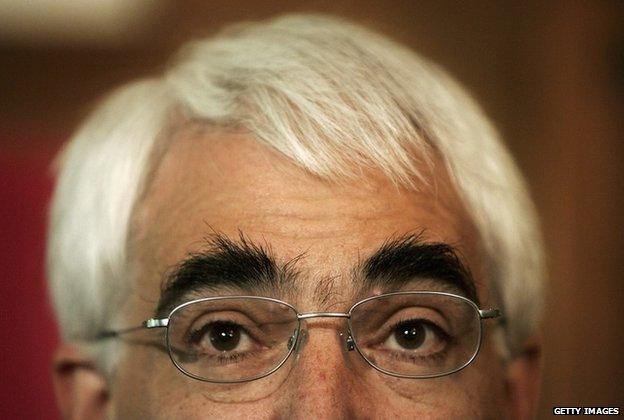

Probably very little prepared Mr Darling for his near three-year stint as chancellor - the job for which he was handpicked by Mr Brown, on his elevation to PM in June 2007.

Mr Darling, predicted by many commentators to be a Brown "yes" man, staked his territory, memorably warning in the summer of 2008 - not long before the collapse of Lehman Brothers - of the worst financial crisis in 60 years.

The chancellor later said the resulting Brown camp backlash was like having the "forces of hell" unleashed on him, but Mr Darling - to many, a reassuring figure during the banking crisis - stood firm.

When Mr Brown apparently tried to evict his long-time ally (and neighbour) from No11 in the summer of 2009, it was widely reported Mr Darling threatened to resign.

Surrounded by "Move over Darling" newspaper headlines and weakened by internal party divisions, the story goes that Mr Brown backed down and Mr Darling remained where he was.

In his memoirs, published after Labour was voted out of office, Mr Darling said there was a "permanent air of chaos and crisis" when Mr Brown was prime minister.

He also wrote that Tony Blair likened working with his then-chancellor to "having dental treatment with no anaesthetic". Ouch.

Out of office

Despite losing the election, Mr Darling was possibly able to take some comfort that his prediction of financial meltdown was, as he put it, "fairly accurate".

And his survival skills ensured he was one of only three - along with Mr Brown and Jack Straw - to remain in cabinet between 1997 and 2010.

After Labour's defeat at the polls and Mr Brown's resignation as PM, Mr Darling was talked of in some quarters as an interim leader.

He remained MP for Edinburgh South West, but decided to step back from frontline politics. But not for long.

Fight for the Union

Despite initially insisting he was not interested in leading the pro-Union Better Together campaign (he was "too busy" as an MP) Mr Darling returned to the fray ahead of the 18 September referendum.

Flanked by Tory and Lib Dem politicians, Mr Darling declared: "If we decide to leave the United Kingdom there is no way back."

Beards out

Back in the day, one of the most famous things about Mr Darling was his insistence on wearing a beard, because commentators deemed facial hair not very New Labour.

Amid rumours he was under orders to get rid, Mr Darling did eventually shave it off.

The beard was reputedly favoured by wife Maggie.