Middle class obscured in a Scots myth

- Published

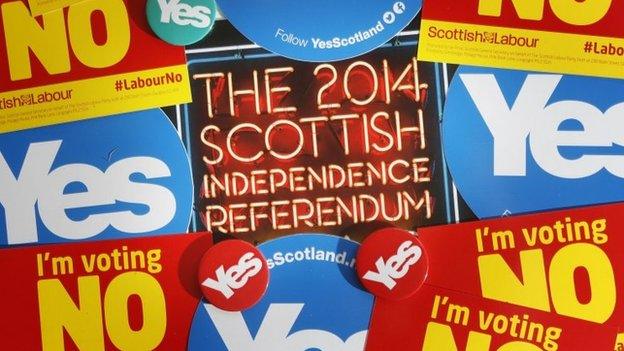

Studies have been trying to establish which groups tended to vote "yes" or "no" - and why

A month on, the referendum reverberates.

We've heard a lot about "the 45%", or at least we've heard a lot from them - the determination to keep the campaign spirit alive, to push on towards independence, and the sense of disappointment that they didn't get a majority on 18 September.

Yet we've heard rather less from the 55% who voted "no". And I've been struck by the lack of analysis by the 45% about how they're going to win over enough of the 55% to achieve their goal.

To be fair, Patrick Harvie of the Scottish Greens has called for just such a reaching out. But the SNP, with a change of leadership, a deputy leader contest and many more members, has focused most of its messaging internally.

In wider commentary, I've read a lot about people being duped or scared into voting "no". This is odd, because insulting their intelligence, calling them cowards or looking forward to them dying (older voters were decisive for the "no" result) seems an odd way of going about convincing people to change their minds.

It might be more productive to find out who these people were, because one of their characteristics was that they were more reticent about their vote, and the reasoning behind it, than those on the losing side.

Deprived vs affluent

So, who were they? Well, for now, there's limited polling evidence. Prof John Curtice at Strathclyde University has looked at two surveys carried out while the polls were open - one by YouGov and the other by the Conservative peer Lord Ashcroft, who appears to be turning his party polling into a public service.

The professor concludes, external that those more likely to vote "no" were older voters, as well as women, those in more prosperous social classes, and those who were born outside Scotland.

Prof Curtice concluded those in more prosperous social classes were more likely to vote "no" to independence

Let's take a look at one of these categories - the better off. It's been widely noted that the council areas voting with a majority 'yes' were among the poorest in Scotland - Dundee, West Dunbartonshire, Glasgow and North Lanarkshire. It seems the poor were either more attracted by independence, or that they felt they had less to lose.

But what of the flipside of that? What of those who did think they had something to lose? The psephological prof tells us that if you divide the country through the middle of its socio-economic cake, the two polling day surveys show the ABC1s were 44% for "yes" and the Cs and Ds were 50%.

However, we're cutting the cake with a blunt knife. Ipsos Mori offered a more detailed breakdown in its final two pre-referendum polls, says Curtice. and "no less than 65% of those living in one of the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods in Scotland voted Yes, compared with just 36% of those in the one-fifth most affluent".

Routine workers

That's a clear gap, but further evidence confuses the picture. Jon Mellon of Oxford University has drawn on academic survey work, external from early this year, which found a mixed picture on "yes" and "no" support, when broken down by occupation.

He found that support for independence was highest among supervisors, small business owners and people classified as routine workers, such as those on assembly lines, waiters and cleaners.

Jon Mellon of Oxford University found support for independence was highest among "routine workers", including those on assembly lines

It was so-called intermediate workers, such as secretaries and computer operators, along with senior managers, who showed the lowest support for independence.

That suggests there wasn't a direct link between prosperity and "no" voting. The type of work, rather than your salary level, looks like a significant factor, and an unpredictable one.

The Oxford don also looked at home ownership, and the picture is a bit clearer there. Those who own their homes outright (the better off and the older) were only 32% for independence. With a mortgage, it rose to 41%. But "yes" support was around half of those in council homes or with housing associations.

So, with those on lower pay (generally), in social housing and in poorer parts of west central Scotland being more likely to back independence, one question that arises is what it tells you about the loyalty of Labour's traditional core vote (clue: it doesn't look great for Johann Lamont).

Silent majority

But again, the flipside can get ignored - those living in their own homes, in the more lucrative white collar jobs, who were less likely to support independence.

Was it because they felt more British? That they were more head than heart, and didn't believe the claims made for independence? Or that they feel they have more to risk and more to lose?

My hunch is that the silence of the so-called "silent majority" was because it was the latter. They have a stake, they don't want to lose it, but they didn't want to shout about it either.

More than that, you could argue that it's these people who have benefited most from devolution over the past 15 years, and they quite like things as they've been.

They're the ones who might have to pay for student tuition fees and care for the elderly if it weren't for Holyrood budget decisions. If council tax hadn't been frozen for seven years, their bills would have gone up by much larger amounts than those in less valuable housing.

Whatever their grumbles and their insecurities, they have reason to like the status quo rather than wanting to stir it up.

Roots vs lifestyle

Let's dare to call these people, diverse as they are, Scotland's middle class.

It owns its own home (that's more than 60% of Scottish homes), it's upwardly mobile through higher education, it's got an occupational pension, some savings, loans (yes, significantly, they want them to remain secure and in sterling), and it's got spare cash to spend on foreign holidays.

Scotland's middle class is a large group. with a lot of clout

It's a large group. It's got a lot of clout, with its consumer, its lobbying and its voting power. And yet it's rarely part of the story Scotland tells about itself.

Ask yourself this: although the more prosperous part of Scotland is a big consumer of culture, how much is there in contemporary Scottish culture - films, books, theatre and so on - that reflects the middle class back to itself?

The story we hear and see and read is more often about poverty and social injustice. It's much more about an urban working class and, to some extent, a rural crofting classlessness.

That's perhaps because those who live an apparently middle class lifestyle are often found to identify with working class roots from previous generations. They are deemed to have more community-oriented, meritocratic, public service values than in other parts of the UK.

And working class identity has stayed with many people when they vote, which has long been to the benefit of Scottish Labour, and to the frustration of Scottish Conservatives.

Mental imagery

Yet analysis by Prof Ailsa Henderson at Edinburgh University suggests there's a lot of myth behind this, external. On three measures of individualism, liberty and social justice through welfare, she found it's hard to see significant difference between the Scots and the English.

But ask people how they see their part of the UK, and Scots respond they think their country's values are different - much more so than they actually are.

"Scots believe they are distinctively left wing, their belief in this distinctiveness is reinforced by the rhetoric from politicians and civic organisations, and it then comes to form part of the mental imagery of Scottish national identity," writes Prof Henderson.

In other words, what people see in their own lives doesn't match up with their perception of their fellow Scots as a collective.

This is a powerful myth. It can shape the way society shifts, if politicians legislate for the country they think they run, rather than the country as it actually is. It can make it seem that more prosperous Scots are generously minded to the less fortunate.

But what if the decisions politicians make, and the changes for which they argue, come up against the perceived interests of the more prosperous majority?

The "yes" campaign may have discovered the answer to that when the results came in one month ago.

You could hear it again this month when the Scottish government tilted the homes transaction tax against those buying the most expensive houses - a very rare Holyrood example of redistribution for explicit social justice reasons.

If those in favour of independence want to change Scotland and the way Scots vote, it may have to criticise the "no" voters less, and understand better how the rest of Scotland thinks.