Smith Commission: Party representatives hold 'constructive' first meeting

- Published

Representatives of five political parties attended the meeting, chaired by Lord Smith of Kelvin

The Smith Commission on more powers for the Scottish Parliament has held a "constructive" first meeting, its chairman has said.

Lord Smith said representatives of Scotland's main political parties had "committed to work together to achieve a positive outcome".

The SNP, Labour, the Conservatives, the Lib Dems and the Scottish Green Party have all set out devolution proposals.

The commission is expected to reach an agreement by 30 November.

Following its first full meeting, the commission said it had agreed a set of principles for the cross-party talks, but added there would be no agreements announced in any policy area until it had considered submissions from the public.

Members of the public and Scotland's civic bodies have until 31 October to submit their views.

The agreed principles included a commitment that the outcome of talks would not be "conditional on the conclusion of other political negotiations elsewhere in the UK".

'Important principles'

Lord Smith said: "We have good people around the table, each with their own deeply-held views, who have committed to work together to achieve a positive outcome to this process.

"We had a constructive discussion and agreed some important principles, which will guide us towards an agreement on a package of substantial and cohesive new powers to strengthen the Scottish Parliament within the UK."

Lord Smith says the first meeting of the commission set-up to deliver further devolution to Scotland has made: "a good start"

The party representatives agreed that they would not comment on the talks until they had concluded and a final report had been produced.

The first meeting produced an agreement that the eventual outcome would:

form a substantial and cohesive set of powers;

strengthen the Scottish Parliament within the UK;

bring about a "durable but responsive" constitutional settlement, which maintains Scotland's place in the UK

not be conditional on the conclusion of other political negotiations elsewhere in the UK

not cause detriment to the UK as whole or its constituent parts

cause neither the UK or Scottish government to gain or lose financially simply as a result of devolving a specific power

be compatible with international obligations, including EU law, and be agreed with a "broad understanding" of potential costs

ANALYSIS

By Brian Taylor, BBC Scotland political editor

The Smith Commission is an intriguing creation, operating at different levels.

It is not the cross-party Constitutional Convention which paved the way to Scotland's Parliament in the first place - nor is it the Calman Commission which generated enhanced powers in the Scotland Act 2012.

For Lord Smith of Kelvin, "l'etat, c'est moi." He sits, alone and palely loitering.

Alone, that is, apart from some of the smartest civil servants on these islands.

Alone apart from the torrent of advice which will come his way, not least from the political leaders.

Unlike the Convention, unlike Calman, this is not a cross-party body. It will not - at least overtly - involve a cross-party fix.

The senior political figures - and they are decidedly senior - who attend today are interested advisers, not members.

Prime Minister David Cameron announced the establishment of the commission after voters in Scotland rejected independence in September's referendum.

The five parties in the Scottish Parliament each have two representatives on the commission:

The SNP is represented by Scottish Finance Secretary John Swinney and Linda Fabiani MSP.

Scottish Labour has put forward finance spokesman Iain Gray MSP and shadow work and pensions minister Gregg McClymont MP.

Former Scottish Conservative leader Annabel Goldie will represent her party, alongside Glasgow University law professor Adam Tomkins.

The Scottish Liberal Democrats are represented by former Scottish Secretary Michael Moore MP and former party leader in the Scottish Parliament, Tavish Scott MSP.

The Scottish Green Party's co-leaders, Patrick Harvie MSP and Edinburgh councillor Maggie Chapman, will also give their opinions to the commission.

Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, who campaigned against independence, have all promised further powers for Scotland in areas including taxation, the economy and employment.

The commission is tasked with finding common ground between the pro-Union parties and the more radical submissions from the SNP and Scottish Greens.

What next for Scotland's future?

During the referendum campaign, David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband signed a pledge to devolve more powers to Scotland, if Scots rejected independence.

Immediately after the result became clear, Mr Cameron appointed Lord Smith of Kelvin to oversee the implementation of more devolution on tax, spending and welfare.

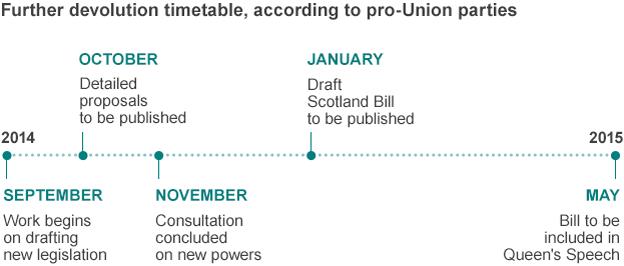

A white paper is due at the end of November, after a period of consultation.

A draft new "Scotland Act" law would be published by Burns Night (25 January) 2015 ready for the House of Commons to vote on.

And legislation would be passed after the 2015 General Election.

Follow the story with the BBC by going to our special Scotland: What Next? page.

While Labour has proposed giving the Scottish Parliament control of around 40% of the revenue it raises, the SNP has argued that all tax revenues should be retained in Scotland, unless there is a "specific reason" for any to remain reserved to Westminster.

Last week, MPs and academics argued, during an Edinburgh meeting of Westminster's Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, that the timetable set out for the commission was "unrealistic".

But Lord Smith argued, ahead of the first meeting, that agreement was possible.

'Not easy'

Nicola McEwen, who is a politics professor at the University of Edinburgh, warned that a "swift agreement" would not come easily.

She told the BBC: "These are different parties with different proposals, not just the UK parties, but the SNP and the Green Party too and then there is all the submissions from civil society and the public that are part of the mix.

"So, it would be extraordinarily difficult to get agreement in time for the end of November - an agreement that can satisfy enough people."