Grangemouth a year on: energy prices and business attitudes

- Published

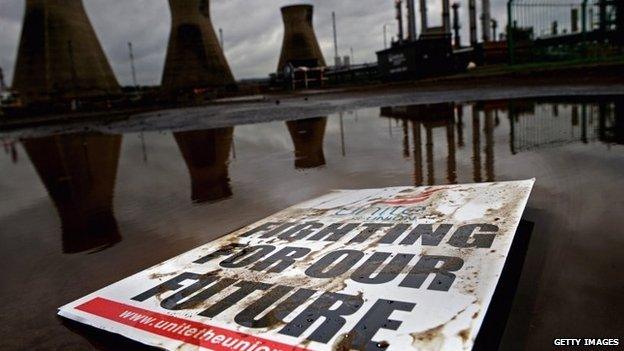

The Grangemouth dispute ended with unions accepting changes to pay and pensions

A year since the Grangemouth dispute, and the energy markets are in an even more topsy-turvy place.

We're told by the Scottish Trades Union Congress that the dispute didn't change industrial relations in Scotland - though that's not how it looked from outside.

Unite, the main union at Grangemouth, is not talking publicly about what it's learned - not while there's a rather sensitive industrial tribunal on the way.

One of the things the rest of us learned is that industrial relations - no surprise here - are stacked in favour of employers, particularly those who are willing to call the unions' bluff, and where unions are woefully lacking in any strategic sense.

Bosses such as Jim Ratcliffe - who controls petro-chemicals giant Ineos and who closed down the Grangemouth petro-chemical plant last year until the unions gave in to his demands and more - can use economic fundamentals to back them up.

And the fundamentals of the energy market are about cheap shale gas from the US exporting a whole lot of volatility to the old order of things.

The Grangemouth plant is being re-tooled and re-equipped to handle bulk carriers full of shale gas from the US. That's after it ran out of adequate feedstock from the North Sea.

Energy giant

And this week, two reports showed how much that trans-Atlantic trade is changing things. The US government said that July saw the highest monthly exports of crude oil for 57 years, and the second highest since records began in 1920.

Because the US puts tight constraints on crude oil exports, much of that is Canadian oil being sent by rail to the Gulf of Mexico, and on to Switzerland, Italy, Spain and Singapore. If pipelines are opened up to North America's coasts, the economics of such a trade could make more such exports viable.

Also this week, Wood Mackenzie, the Edinburgh-based energy consultancy, pointed to the US moving from being an "energy-consuming giant to a prominent exporter" as early as 2025. That would be the first time it's been a net exporter since 1952.

Not only is oil and gas production up by 42% in seven years due to the new technologies for fracking and oil from tight rock formations, but the US is also seeing big leaps in energy efficiency, particularly in transport.

The variables are around whether environmental constraints are placed on fracking, given the controversy that surrounds it (and Jim Ratcliffe is buying up licences for unconventional gas in the UK), and also whether US energy efficiency gains will continue. That is, will Americans give up light trucks and SUVs in favour of mere cars?

If the US is to become a net exporter, and of cheap energy, it would alter the basics of the energy economy for the rest of the world, including downward pressure on the Brent crude benchmark, from the North Sea, on which the non-North American world trade is based.

It finished this week above $86 per barrel having fallen as low as $83 in recent days. That's down from $115 in June, and close to the range when operators in UK waters say they are likely to shelve a lot of investment plans and accelerate shut-downs of older fields.

Fracking has been partly responsible for a big increase in oil and gas production in the US in recent years

A final thought a year on from the Grangemouth dispute is about our attitudes to business, and about businesses attitudes to the rest of us.

YouGov published a Britain-wide survey this week, external which makes for interesting reading.

To pick out a few of the highlights, 61% of us think business is a force for good, and only 12% think it's destructive. That's the positive bit.

Asked if regulation-free business would look after employees or work them longer hours for lower pay, the public overwhelmingly think bosses would abuse their positions.

Asked if unregulated business would let down customers, with shoddy goods and services, the public's trust remained very low. Employment law and consumer protection are apparently two areas where people like to have government interference.

Asked about attitudes, the public gave a positive score only to the operators of small businesses, at +8%. The ratings for those running big business and for entrepreneurs are pretty awful, at -56% and -27% respectively.

So what should the boss of a big business get paid? The public think £75,000 would be fair.

YouGov spent some time hearing from those bosses, and asking how think they're seen.

Among the themes running through answers was that the bad image the banks have earned for themselves has spread to affect all forms of big business.

Some of the telling quotes, though unattributed:

"Something went wrong in the 2005 to 2008 period, everyone played a role - business, banks, politicians, regulators and consumers - but bankers got a disproportionate amount of blame. The regulators and the government were able to wriggle out of their share very successfully."

Another said: "We have not moved on from the blame game and the bloodletting of the recession."

And another: "You can't talk yourself out of things you have behaved yourself into. You have to change things."

Threatening calls

They really don't think much of Ed Miliband, though they sound more tolerant of Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls.

And at least three of them did a bit of reflecting on the Scottish independence referendum:

1. "There were three reasons why business failed to step up early in the referendum: first, there was complacency, the sense that it wasn't needed and was going in the right direction on its own, second there was concern that we would be someone shouted down, and third was the fear of retaliation from the SNP. This was very real, Alex Salmond was always on the phone threatening us."

2. "Business did come out and make the points about the dangers to the Scottish economy. That worked because we were talking about things we were believed on."

3. "In the end what we did in the Scottish campaign, speaking out in spite of the threats, and being listened to and having an effect, will encourage business to engage more."

On European Union membership, for instance? Or on Scotland's future?

- Published23 October 2014

- Published23 October 2014