Could the Scottish National Party run 'United Kingdom plc'?

- Published

What political blossoms will grow as spring approaches?

Six months ago the Scottish National Party's fight to see Scotland leave the UK was building to a climax. Its vision of independence did not come to pass. However, could it end up running the very thing it was battling against?

As the crocuses poke through the soil, the bright purples and yellows singing of spring, we can bury one idea in the damp earth.

A formal coalition government at Westminster involving the Scottish National Party is not about to bloom.

Alex Salmond will not be climbing into a ministerial Jaguar with a red box of British state papers after the general election on 7 May.

Such an image would provoke outrage in England and, much more importantly for Mr Salmond, the howls would be even louder from the SNP's huge membership back home - 93,000 at the last count.

It simply won't happen, even if Mr Salmond and colleagues are elected to parliament.

But could the SNP prop up a UK government on an informal basis?

It depends, first of all, on arithmetic.

Who has said what?

Prime Minister David Cameron: "Even today, Ed Miliband will not rule out a deal or backing from the SNP"

Alex Salmond: "After generations of having so little influence at Westminster we will like upsetting the apple cart"

Polls suggest the nationalists could take almost all of Scotland's 59 seats at the general election.

These are incredible predictions. In 2010 the SNP returned six MPs. In the party's 80 year history its high water mark was 11 seats, in the autumn election of 1974.

The Conservative peer and pollster Lord Ashcroft has suggested the 2015 election may be heading for a dead heat, external with Labour and the Tories on 272 seats each and the SNP with as many as 56 MPs.

Clearly that would leave the two main parties a long way short of a theoretical majority - 326 seats - in the House of Commons.

If the result in Scotland this time really is an SNP landslide then its leader Nicola Sturgeon could find herself dangling the keys to Downing Street in front of David Cameron and Ed Miliband.

So what price entry?

The Scottish National Party would not countenance any agreement with the Conservatives, who are relatively unpopular in Scotland where they have just one MP, although the Tories did take a 16.7% share of the vote north of the border in the last general election, not a million miles from the SNP's 19.9%.

Since losing last year's independence referendum, Ms Sturgeon has suggested she might prop up a Labour minority government in return for three main policy commitments: more power for the Scottish Parliament; an end to austerity; and a decision not to renew the UK's Trident nuclear weapons system, which is based on the Clyde.

Lord Baker of Dorking says there is a "great threat" the UK could be broken up

The working assumption was that the first minister would try to strike a "confidence and supply" deal with Labour's Ed Miliband, in other words she would agree to support his party in the House of Commons on votes of confidence and the budget if she had received assurances on her "red line" issues.

Having apparently revealed its negotiating hand the SNP is now busy trying to cover it up again.

Language about "red lines" on Trident and austerity appears to have given way to a more subtle approach.

Although she insists her MPs would never vote to renew the nuclear weapons programme, Ms Sturgeon now appears to be suggesting they could support Labour on an issue-by-issue basis, external without the need for any pre-negotiation at all.

If Labour were the largest party but short of a majority, that might work - at least for a while - but sooner or later it would surely run into trouble, perhaps in a vote of confidence, perhaps in a vote on renewing Trident, perhaps in a budget which included new funding for the nuclear programme.

At that stage the SNP would hope to turn the screw on Labour, securing concessions in return for continuing support.

The SNP seems to have adopted a more subtle approach on the issue of Trident

They cite their own experience as a minority government in the Scottish Parliament from 2007-2011 which they survived, not with a formal deal, but with a combination of concessions, bravado and issue-by-issue support from opposition MSPs including, ironically, the Tories.

Interestingly the message from Ms Sturgeon's predecessor Mr Salmond sounds rather different.

Addressing supporters on Friday night in the Gordon constituency, where he hopes to be returned to Westminster in May, Mr Salmond said SNP support for any administration would come with "the condition of progress for Scotland."

Either way, would they really be in as strong a position at Westminster as they hope?

The notion of separatist social democrats imposing left-wing spending plans on the "Tory shires" and forcing the UK into a dramatic shift in defence and foreign policy would be controversial to say the least.

Follow the election story

Keep up-to-date with all the twists and turns of general election campaigning by going to our politics pages.

Have a look at our poll tracker on the UK-wide picture.

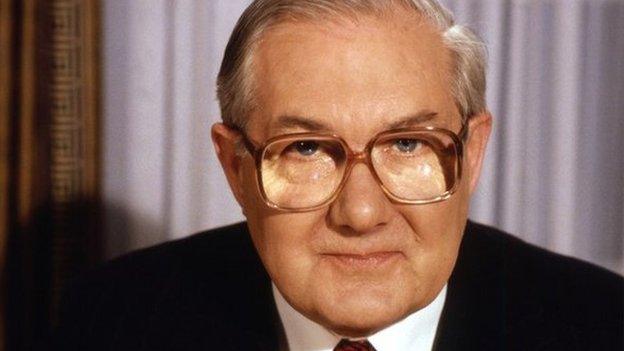

The former prime minister Sir John Major is not the only senior UK politician to warn of the dangers of Scotland imposing its will on England, external.

Independence-supporting websites, external are quick to point out that Scotland has tried to reject the Tories in every election since 1955, only to find itself governed by them for more than half of those 60 years.

You told us this was the price for a prosperous, secure union, they say to unionists. Why shouldn't other parts of the United Kingdom pay that price sometimes?

There are two obvious retorts to that. First, England has rejected Labour in the past only to find occasionally the party governing anyway thanks to Scottish votes. Second, why do two wrongs make a right?

For the SNP though, winding up the English isn't necessarily a problem. Scottish nationalists didn't get into politics to ensure the harmony and stability of the British state. They got into politics to break it.

To do so they must retain credibility with the electorate in Scotland, nowhere else. And here, history matters.

Those 11 SNP MPs elected in October 1974 went on to achieve a certain notoriety back home by voting in 1979 against the Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan in a confidence motion.

Mr Callaghan lost by a single vote, Margaret Thatcher became prime minister and much of Scotland spent much of the 1980s in a state of seething resentment about the Conservatives.

Jim Callaghan lost a confidence motion after 11 SNP MPs voted against him

Although they insist Mrs Thatcher would have been in Number 10 within months regardless of their votes, the SNP have never entirely shaken off the "Tartan Tories" taunt.

With that in mind, an SNP decision to effectively bring down another Labour government would carry a huge risk.

There is, say Labour, a simple solution to all of this.

Every Labour seat lost to the nationalists heightens the "nightmare prospect" for Scotland of "vicious austerity" from a Tory government, says one source close to Mr Miliband.

The largest party forms the government, say Labour - especially if that party is already in power - and every seat lost to the SNP makes it more likely that the Conservatives will be the largest party.

Maybe. Forming a government is all very well but if you can't command a majority in the Commons that government won't last long and perhaps someone else can have a shot.

Why risk it, ask Labour activists on the doorsteps in Scotland, when the arithmetic is so uncertain?

So far the polls suggest that message isn't working.

How voters in Scotland respond to these competing arguments could have a profound effect on the future of the United Kingdom long after spring has turned to summer.

- Published7 March 2015

- Published6 March 2015

- Published7 March 2015