EU ref differences less marked in Scotland

- Published

A referendum engenders an intriguing range of issues - and curious allegiances. Even more than in a General Election where most follow Disraeli's advice: "Damn your principles, stick to your party."

Political parties, of course, are all coalitions of the more or less willing. But, again, when they are presenting themselves to the voters at election time, they commonly contrive to subsume most of their differences.

A referendum, by contrast, tends to find fissures in the standing political structure. Generally, those will have been pre-existing - as is the case with Conservative differences over Europe. A popular plebiscite on a single issue draws those differences out.

However, as noted previously, the differences appear notably less marked in Scotland. There is a range of reasons for that.

Firstly, the largest party is the SNP - which has long displayed a remarkable self-discipline with regard to its public facing standpoints. I stress "self-discipline". This is not, for the most part, whipped.

Rather, the SNP is a cause as well as a political party. The adherents are so thirled to that cause - of independence - that they tend to cluster together on most issues, regarding any display of internal division as a weakness to be exploited by their opponents. Whom, they suspect, do not require much encouragement.

That is not to say that the SNP is uniformly supportive of Remain in this referendum. Jim Sillars is not alone in regarding it as inconsistent to support Scottish independence from the UK but not British departure from the EU.

Former SNP deputy leader Jim Sillars is campaigning for a Leave vote

There are others, including serving MSPs, who hold that view. However, they tend not to speak out (see above). And, to be clear, the vast majority back the argument - which Mr Sillars used to deploy - that "Scotland in Europe" allows the SNP to insist that they are not leaving Britain but joining the EU on level terms.

Secondly, the Conservative Party in Scotland - despite its recent relative success - is not the force it is in England. They have only just begun to revive, potentially, from a slump which was largely occasioned by another constitutional question, that of devolved self-government.

Thirdly, UKIP is also not the force it is in England - there, potentially posing a challenge to the Conservatives and thus, arguably, prompting the referendum in the fourth place.

Fourthly, as I have argued previously, this referendum is partly about English identity. The good and sensible people of England are asking themselves questions about their standing in the world. That internal interrogation is driven by three factors: the Union (aka "what are the Scots up to?); immigration; and Europe.

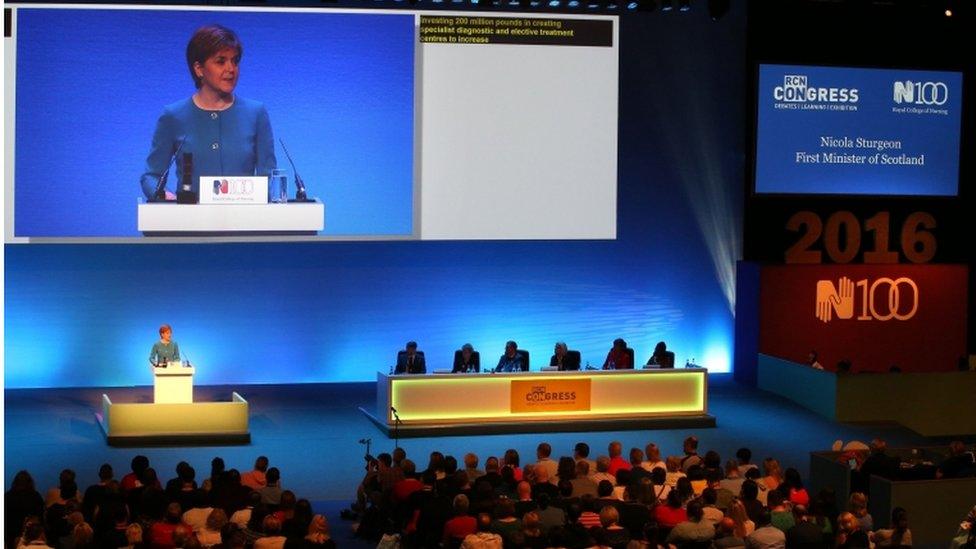

Nicola Sturgeon used her keynote address at the RCN congress to argue for a Remain vote

Scotland, of course, has been wrestling with the issue of identity. But the conduit tends to be devolved self-government and independence, rather than the EU.

So a curious amalgam. And diverse content today. In Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon tells the RCN's UK congress in Glasgow that Brexit represents a threat to the health service. How so? Because, she says, the economy would nosedive, resulting in spending cuts.

Plus, she argues further, there would be a new Conservative UK government defaulting to the Right, with a possible impact on health policy, ultimately affecting Scotland through Barnett consequentials if the NHS in England is reduced in scale.

These arguments are contested by supporters of Leave. In Edinburgh today, David Coburn, UKIP's Scottish leader, says Ms Sturgeon cannot be trusted on health issues. He argues that her own record is poor.

Meanwhile, in the Commons, MPs from all sides pay tribute to the late Jo Cox, wearing the white rose of her native Yorkshire in solidarity.

- Published20 June 2016