IndyCamp: Sovereignty and spirituality at the Court of Session

- Published

Lord Turnbull is to issue a written judgement which will decide the fate of the IndyCamp

A judge has retired to consider whether Holyrood independence campaigners can be evicted from outside the Scottish Parliament, after a six month legal battle at the Court of Session. BBC Scotland political reporter Philip Sim has been following the case from the beginning.

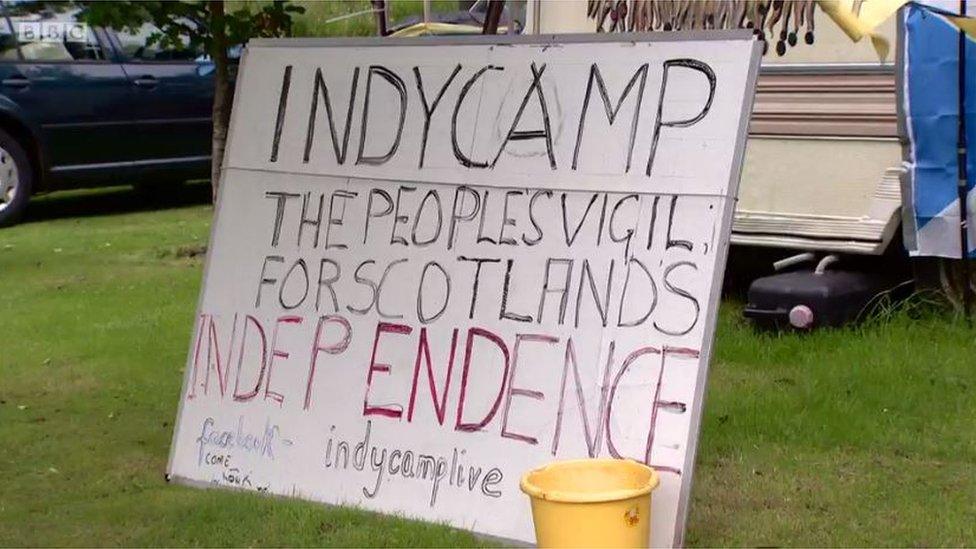

It started out with just a couple of tents.

The IndyCamp case has delivered some of the most unusual courtroom exchanges the Court of Session has seen in recent memory - and we still don't know just how it will end.

The case, which has seen the Queen unsuccessfully cited as a witness, attempts to "invoke" the Declaration of Arbroath and a judge accused of blasphemy in light of the second coming of Christ, all hinges on a tiny encampment outside the Scottish Parliament.

When they first pitched up in November 2015, the campers, diehard Scottish nationalists one and all, said they said they wanted to stay in place until Scotland was declared independent.

Things didn't seem that complicated, back then; a pregnant Jack Russell due to have puppies on Christmas Day was the extent of the campers' worries.

They had based their plans on the "Democracy for Scotland" vigil, which stood at Calton Hill for five years campaigning for devolution - successfully, in the end.

However, the parliament's corporate body had other ideas.

They ordered the campers to get off their land, arguing that they needed to maintain strict political neutrality on the parliamentary estate.

And when the campers refused to leave, they initiated court proceedings. Six months later, those proceedings might finally be coming to a close.

When it was first set up as a collection of tents, a pregnant Jack Russell was the extent of IndyCamp's worries

The case had to pass through a series of procedural hearings before the facts of the case were debated, and each one seemed stranger than the last.

For the early hearings, the Court of Session was packed; bewigged advocates and QCs mixed with activists in full Highland regalia in the corridors. One camper had to be prevented from bringing a bongo drum through the metal detectors.

The campers initially struck on an idea that if they could get a hundred of their supporters into the courtroom, they could try to invoke the Declaration of Arbroath, a seven hundred year old document which proclaims that "so long as only one hundred of us remain alive, we will never be brought under English rule".

Their problem was that the capacity of Court Two at Parliament House is closer to 80, which left a good number of disgruntled campers shut out.

The Declaration aside, they still found a multitude of ways to shake up the judicial system.

Sovereign and Indigenous

The IndyCampers christened themselves the Sovereign and Indigenous Peoples of Scotland, and found 238 people to sign their names to backing the camp.

There was immediately contention over this, as all listed their address as the Holyrood camp - meaning it would be very difficult for the court to effectively enforce any order against them.

In addition, the primary speaker for the camp insisted on being referred to only as "David" in court, refusing the title of "Mr Patterson", explaining that the case was being answered by "the sons and daughters of Scotland".

When it came down to it, 10 campers eventually gave their names and home addresses to be part of the formal hearings.

Apparently with some sense of history, the judge, Lord Turnbull, scheduled the full hearing to be held on the 24th of March - the date on which Scotland would have become independent had the Yes side won the 2014 referendum.

The campers attempted to pack 100 of their supporters into the Court of Session

The campers argued that the Scotland Act, which set up the Scottish Parliament, clashed with the 1707 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom - meaning the parliament had no jurisdiction and Scots law couldn't be applied to the case.

They also questioned who owned the parliament - there was a suggestion that it might in fact be owned by Murray Tosh, a former Conservative MSP whose name appeared in the depths of some paperwork due to his one-time role as deputy presiding officer.

There was also a claim that the Scots were an indigenous people, and as such entitled to protection under a UN declaration.

'Agree to disagree'

The highlight of the hearing was an extraordinary clash between Lord Turnbull and a second respondent in the case, Arthur Gemmill.

Mr Gemmill said he wanted to contest the case based on "ancient or common law", before trying to explain to Lord Turnbull how Scots and English law are different.

He contended that the parliament had no physical body - at one point trying to persuade it to hold his glasses for him - and thus could not be subject to laws or own land.

He also insisted that only God could make laws for men, and when Lord Turnbull pointed out that this may not be the case, Mr Gemmill suggested that they "agree to disagree" - perhaps missing the point of court proceedings.

This was the point at which the case really exploded into the public consciousness. Both "Lord Turnbull" and "Murray Tosh" were trending across the UK on Twitter, and when I checked the statistics on my account, external, it had had over half a million hits that afternoon.

Qualified lawyers started blogging about the case. People talked about taking a day off work to come and see Mr Gemmill speak at the next hearing.

The BBC's coverage of the court case developed a devoted following on Twitter

Having heard arguments on what would have been "independence day", Lord Turnbull then issued his judgement on the day of the Scottish Parliament elections.

He rejected the arguments put forward by the campers one by one, saying they had "no legal foundation", but also refused to grant the petition put forward by the parliament.

He said there was still a question over whether evicting the group would be a proportionate response, or if it could breach their human rights - and so he ordered a further hearing.

As with every stage of the IndyCamp case though, things didn't entirely go to plan.

The rightful monarch

The group demanded extra time to find a lawyer, and despite warning them that they were wasting the court's time, Lord Turnbull allowed an extra four weeks.

And when he tried to check in on their progress in this search, the case reached a new level of unconventionality.

One camper, Richard McFarlane, explained to the judge that he had contacted 144 lawyers, without success - and he ventured a theory why this might be.

Some of the IndyCamp group were on a spiritual mission. Mr McFarlane explained to the judge that Christ, the son of God, had returned to Earth, and was the "rightful monarch" of Scotland. Lawyers seemed reluctant to take on a case involving the second coming.

The Court of Session has witnessed some usual arguments during the case

Mr McFarlane then asked for permission to call the Queen as a witness in the further procedure, due to his belief that she was not the true monarch as she was not crowned on the true Stone of Destiny.

He wanted to get a hold of the true Stone, so he could crown Christ The Second on it as the King of Scotland.

At this slightly dizzying point, Mr Gemmill interjected once more, to accuse Lord Turnbull of "blasphemy".

He said the judge had "ridiculed" his belief in God, although he struggled to find evidence of this in the written judgement.

This was one of several points at which Lord Turnbull - exhibiting extraordinary grace and patience throughout - declined the opportunity to charge one of the respondents with contempt of court.

He wearily pointed out - repeatedly - that he could only judge the case based on the law, not on the merits of a philosophical or religious argument.

But this was far from end of the judge's spiritual problems.

'Capital crimes'

At the next, and potentially final hearing, Mr McFarlane produced an affidavit, which came complete with a hand-written signature from "Christ, King of Scotland".

In it, the writer proclaimed himself owner of the entire world, and said he had given the camp permission to use his land and buildings.

He also noted that the "pretended judges and their fraudulent Queen are guilty of capital crimes and should all be executed".

Even with my fairly basic legal training, threatening the entire judiciary with execution did not appear to be a great strategy to win over a judge.

Fortunately for the campers though, three of their number had defied expectations and come to court equipped with the services of a lawyer.

The camp has grown from tents into caravans over the past six months

Advocate Jamie Gardiner - somewhat ironically previously an election candidate for the Conservatives, but who did an impressive job bodging together a coherent case with just one day's notice - was able to put forward an argument grounded in human rights law.

The parliament's case was that they weren't restricting the campers' freedom of expression or speech, but really the manner in which they expressed it.

They contended that there were lots of other ways the group could conduct their protest, without permanently occupying land belonging to a third party.

This was where Mr Gardiner based his argument - there was no other way for the campers to carry out this particular protest, he said. The whole point of it was the full-time nature of the vigil, outside the seat of power - this was the "essence" of the protest, and so it would be disproportionate to deny it.

Letters from Christ aside, this is the key argument which the infinitely patient Lord Turnbull is now mulling over.

He closed proceedings saying he needed time to marshal his thoughts, and we now await his written verdict which will decide the future of the camp.

On Saturday, the Queen will formally open the Scottish Parliament. And outside, for now, the IndyCamp vigil lives on.

The IndyCamp argued that their protest can only be carried out in its present form and manner

- Published30 June 2016

- Published5 May 2016

- Published24 March 2016