In-depth Chilcot report raises further questions

- Published

The Chilcot Report studies the build up to and the conduct of the Iraq War

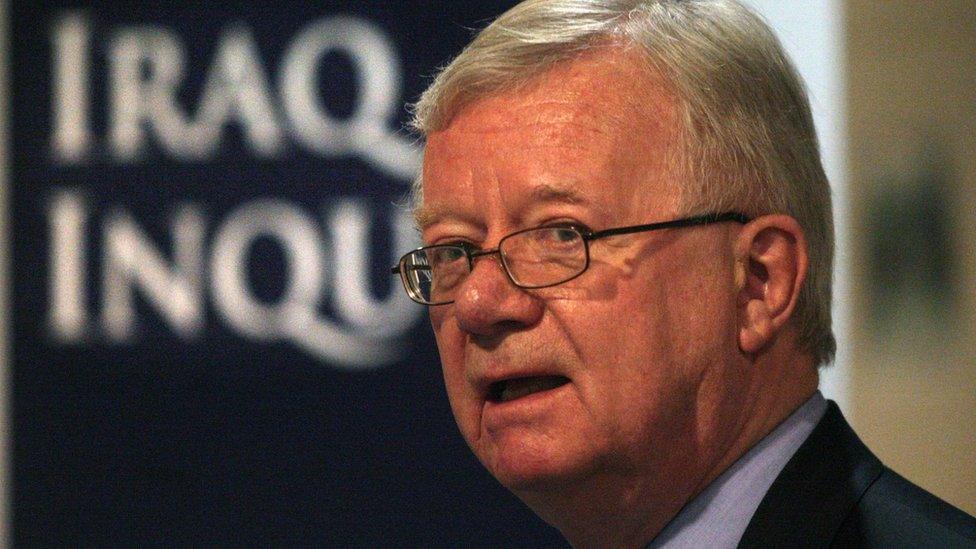

Sir John Chilcot's compendious and coruscating report into the Iraq War and its aftermath has, inevitably, generated further questions.

Could/should the conflict have been prevented? What went wrong with equipping the troops? Why was aftermath planning, according to Sir John, so limited?

And more. Lessons have been identified - but will they be learned? Will the culture of the British state, military and civilian, regenerate fully? David Cameron reckons the answer to both questions is yes.

And more. Will there now be action taken against any individual identified in the report? Against Tony Blair? The lawyer for families who lost loved ones in the conflict says legal action is possible but will require further, detailed consideration. Alex Salmond says Tony Blair is responsible - and political and legal consequences must now be contemplated.

And more. Rose Gentle, a Scots mother whose son Gordon was killed in Iraq, wants a word with the former Prime Minister. For what purpose? She wants to ask him: "Why did you kill my son, send my son to be killed?"

Here's another question. Imagine, for a moment, that Mr Blair was still in office today, on the day the Chilcot report was published. Do you imagine that his tenure at Downing Street would survive such findings?

Sir John Chilcot's report goes into massive depth - but still raises questions

For his own part, Tony Blair argues that the report should "lay to rest allegations of bad faith, lies or deceit." Chilcot finds, says Mr Blair, no falsification or improper use of intelligence, no deception of Cabinet and no secret commitment to war.

The inquiry, he adds, also delivers no finding on the legality or otherwise of the invasion. Mr Blair draws attention to the conclusion by the Attorney General at the time that there was a lawful basis for the military action.

Others might prefer to view the Chilcot findings in a different way. They might note Sir John's finding that the UK opted for military action before peaceful routes had been exhausted, before war was the last resort.

They might note his finding that aftermath planning was "wholly inadequate". That the UK Government failed to achieve its stated objectives.

'I will be with you'

They might note the comment that Britain's diplomatic behaviour, far from underpinning the United Nations, amounted to undermining the UN Security Council's authority.

They might note that the analysis of intelligence, the judgements drawn from it, were presented with a certainty "that was not justified". That the policy with regard to Iraq was made on the basis of flawed intelligence, which was not rigorously challenged.

That the circumstances surrounding the decision that there was a legal basis for UK military action were "far from satisfactory".

That Mr Blair over-estimated his ability to influence US decisions. That it was "an intervention which went badly wrong with consequences to this day". That military action might have been necessary at some point, but not in March 2003.

They might note Sir John's disclosure of a memo, dated July 2002, from Prime Minister Blair to President Bush - in which Mr Blair stressed the critical importance of getting the detail right, given the huge challenge involved. But that he prefaced these strictures with the comment: "I will be with you, whatever."

The report found ex-PM Tony Blair overestimated his ability to influence US decisions on Iraq

So have lessons been learned? It was instructive to witness the tone - and the context - accompanying David Cameron's statement to the Commons.

Perhaps you have to be a Prime Minister, taking such decisions, to understand fully the pressure involved. Perhaps you have to be, as David Cameron now is, a soon to be ex-PM, contemplating legacy.

Mr Cameron addressed, fully, the issues raised by Chilcot. But, speaking as the current inhabitant of Downing Street, he also argued vigorously that planning for military intervention will never be perfect, can never be perfect.

It was not, repeat not, remotely an exoneration of Mr Blair. But it was not a condemnation, either, despite their partisan differences.

Rather, Mr Cameron seemed, perhaps understandably from his perspective, keen to talk about the military engagements in which he has been involved as Prime Minister - and to stress their complexity. Action against Libya, for example, had been carried out with UN sanction - and yet the situation in that North African state was decidedly less than perfect.

Iraq inquiry: 'Lessons must be learnt'- David Cameron

Also, in setting out the lessons learned, he seemed anxious - again, perhaps understandably - to set out and defend his own record in office.

For example, he talked up the National Security Council which he established in 2010, after Britain had left Iraq. That, he said, answered key points from Chilcot about co-ordinated decisions and a forum where officials could openly challenge Ministers, including the Prime Minister.

And wider lessons? Again, Mr Cameron was anxious to look forward, rather than scrutinise his predecessor's past. More precisely, Mr Cameron was keen to avoid any disruption to Britain's core diplomatic and military strategy.

So, he argued, learn lessons from Chilcot - but do not conclude that Britain should abandon close ties with the USA. Learn lessons about the use of intelligence - but do not conclude that it should be neglected.

Learn lessons about military deployment and kit - but do not conclude that Britain should steer clear of global intervention, where necessary, with armed forces which remained the "envy of the world."

Will those lessons now be learned? Fully? Or might the second imperative, of maintaining Britain's perceived objectives, in consort with the US, take priority again, at some point in the future?

- Published6 July 2016

- Published6 July 2016

- Published6 July 2016