Brexit: The entire process is fraught with uncertainty

- Published

Theresa May has rejected a points-based system for EU migrants

Winston Spencer Churchill, most renowned of course as the MP for Dundee, had a word or two to say about democracy.

One of his comments concerned the issue of a five minute conversation with the average voter - but it is far too blunt and forthright for me to use here.

However, he also noted that democracy was the worst form of government - except for all the others. In essence, deal with it.

Our elected tribunes, including the prime minister and first minister, are now dealing, variously, with the consequences of the expression of democracy which was the plebiscite on British membership of the European Union.

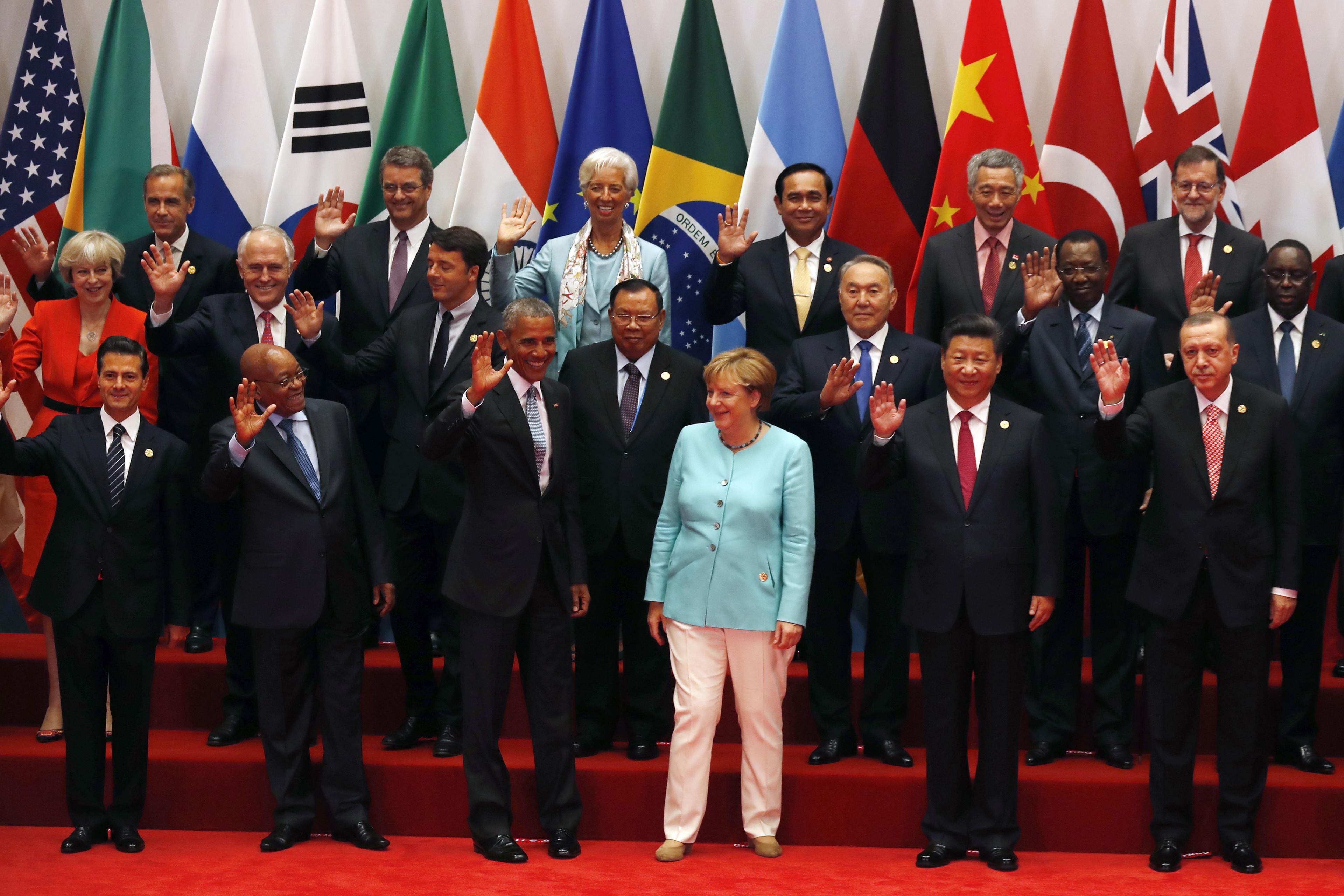

Theresa May is at the G20 summit in China being not so gently chided by her counterparts, such as the US and Japan, for what they see as the global trading downside of Brexit. They seem somewhat unimpressed, at this stage, by the PM's talk of opportunities.

At the same time, Mrs May has been talking about immigration - the issue which played a significant, perhaps deciding, role in the referendum.

During that campaign, there was much talk from the Leave side of an Australian-style points system for determining migration criteria.

Won't do, says the PM. Not enough evident control for the UK. Britain needs a system which allows the UK authorities to decide who comes here and who does not. Not a system which guarantees entry if the points tally up.

Theresa May and Barack Obama were among world leaders at the G20 summit in China

It is yet further evidence that the entire Brexit process is fraught with uncertainty. Although it seems that some folk have been cheerfully reassured by developments thus far.

I was chatting to one senior politician who had met constituents who were encouraged - or, at least, not distressed. Their view was that Brexit had not proved to be a problem. Patiently, my interlocutor explained that it had not happened yet - and would not do so for two years plus.

Right now, there is no clear route ahead. Some have voiced indignation, bogus or otherwise, at this. I cannot join that chorus. Brexit will be fiendishly complex - who ever thought otherwise?

To be clear, that does not mean that it is intrinsically wrong or right. The outcome may be economically damaging, it may be a stimulus to growth. That depends on developments. But easy it is not.

Nicola Sturgeon has told me in an interview that she is willing to help form a coalition with UK political leaders - if it proves productive in advancing Scottish interests, most notably but by no means exclusively through retained membership of the EU single market.

For the avoidance of any doubt, Ms Sturgeon's first preference is for independent Scottish membership of the European Union. Absent that for now and she would prefer that the referendum had not happened or had produced the alternative result.

Absent that - and she is willing, in these difficult circumstances, to seek avenues for defending Scottish interests, as she sees them, through the conduit of UK negotiations.

Ms Sturgeon said staying in the single market was the "least worst position"

In essence, she sees three elements to the post-referendum discussions. She is willing to work with the UK government to secure as much as possible of the EU links, primarily but not solely the single market.

Separately, she intends to seek to protect distinctive Scottish interests - such as the status of our universities.

And the third plank? It is, of course, independence: the raison d'être of the SNP. That third option, she says, remains on the table while the other two are pursued.

To be clear again, that does not mean that independence is ranked more lowly in her pantheon of powers. Just that, in realistic terms, she intends to run with the existing UK negotiations for now.

The calculation, presumably, is that voters might not warm to a straight jump to the independence option at a period when politics is already distinctly uncertain. That, bluntly, there might be more prospect of winning an independence referendum, from the SNP perspective, if it is deferred and the Nationalists have palpably sought to work within the UK framework.

'Troubled world'

Again, given the atmosphere of uncertainty, politicians are mostly being cautious with their language. So Ms Sturgeon says she wants a role in UK talks. She does not demand a veto. For now, she does not insist, as some others do, that Brexit would require ratification by devolved legislatures as well as the UK government or Parliament.

In response, the Scottish Secretary David Mundell is at pains to stress the role which Ms Sturgeon could play in the post-referendum talks.

He must be tempted to say: back off, this is a reserved issue. But he does not. Rather, he talks up the prospect of suggestions, of ideas, coming from the devolved Scottish government.

But, again, there are limits. Scotland, he argues, has two governments: the UK and Scottish. For this issue, it is the UK version which is in the lead. It is, ultimately, he argues, following consultation and wider involvement, the UK government which will negotiate the UK terms for the UK to exit the European Union.

However, all remains uncertain. Perhaps we should not be remotely surprised. The French Enlightment writer Voltaire reminded us that the ideal is scarcely to be expected in this troubled world. Doubt, he said, may not be a pleasant state, but certainty is ridiculous.

- Published5 September 2016

- Published5 September 2016

- Published5 September 2016