The Brexit onion adds another layer

- Published

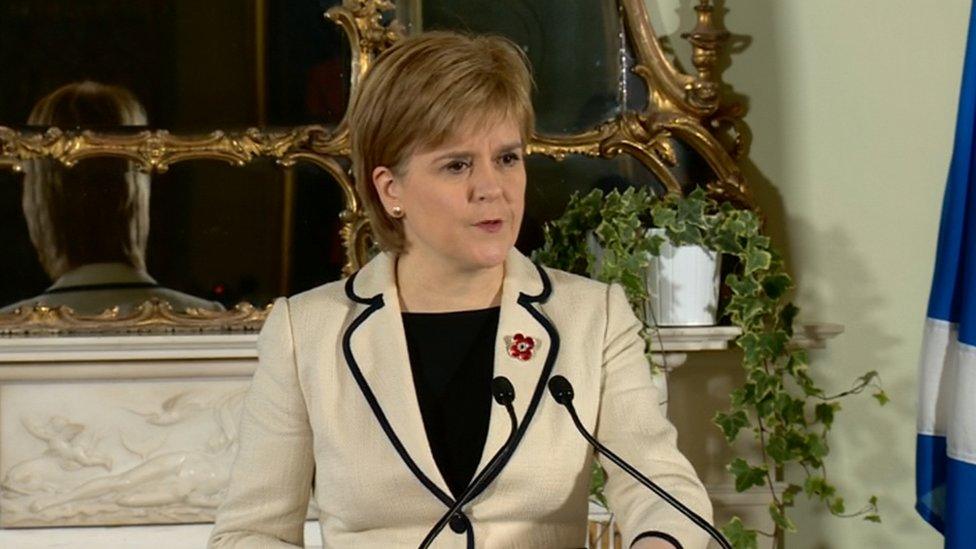

Nicola Sturgeon has pledged to do all she can to protect Scotland's place in Europe

Peeling apart the layers. A tearful experience if one is talking onions. However, I am talking here about the layers presently accreting upon the Brexit debate. We have yet to establish whether the associated tears will be of sorrow or joy.

Layer upon layer today. I make absolutely no complaint. Whoever said this would be simple or straightforward? Including those who advocate the eventual outcome, with varying degrees of fervour.

We learned today that the Lord Advocate, Scotland's senior law officer, wants his day in court. The Supreme Court in London, that is.

The legal system in Scotland has not always looked entirely favourably upon the Supreme Court, distrusting any suggestion that it might arrogate to itself powers which, many Scots lawyers would argue, truly reside in Scotland under the protections granted by the Act of Union.

However, on constitutional matters, the Supreme Court now plays the role, among many others, formerly deployed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council - that is, to settle disputes over where power lies in this devolved UK.

And this case is about power. The power to decide. The power to trigger (or not?) Article 50, the process whereby Britain would begin withdrawing from the European Union.

All 11 Supreme Court justices will hear the appeal

It was about power and democratic mandate already - when the UK government appealed to the Supreme Court to overturn the decision by the High Court in London to the effect that parliament at Westminster must vote before said Article is triggered.

Some, including the prime minister, argue that such a vote is unnecessary and misplaced. They say the true power lies in the popular vote at the EU referendum: a plebiscite called knowingly and wittingly by parliament.

Thereby, she argues, the mandate was ceded by MPs in this particular instance to that popular choice. Nothing should now intervene. She proposes to trigger Article 50, using the Royal prerogative but citing a popular mandate.

Others disagree. They say that Britain joined the European Union (then the Common Market) at the start of 1973 via a Westminster statute. It requires, they argue, parliamentary fiat to reverse that process.

The High Court agreed, arguing that the triggering of Article 50 led inevitably and ineluctably to UK departure from the EU - thus, they argued, subventing due parliamentary process.

To that melange is now added the Scottish dimension. To be clear, it was never far from the surface, particularly for folk in Scotland.

In essence, there are two elements today.

The Lord Advocate wants to offer advice to the Supreme Court on Scottish interests - arguing that the High Court decision should be upheld. That is the legal aspect.

Lord Advocate James Wolffe QC wants his day in court

Then there is parliamentary politics - Scottish Parliamentary politics. Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister, says that Holyrood must also be consulted.

In this, she is relying upon the convention which says that Westminster should not legislate solely upon matters where Scottish interests are affected.

To be clear, Ms Sturgeon does not argue that there should be a Scottish veto. She has never done so. More generally, it is recognised that - convention or otherwise - Westminster remains sovereign and can legislate as it chooses.

This brings us to the mandate issue. Theresa May cites a UK mandate supplied by the UK people. But Nicola Sturgeon, as a Scottish Nationalist, challenges that - just as she challenges the intrinsic nature of the Union settlement.

She considers the referendum vote in its constituent parts, arguing that the people of England and Wales are entitled to expect Brexit. But not Scotland.

That mandate issue can be debated politically and may even feature in the courts. But I suspect that there is also a third dimension to Ms Sturgeon's initiatives.

She wants to be taken seriously when she says she will defend Scotland's interests, including protecting, where possible, links with the EU.

She wants the UK government to take that position seriously, starting with ministerial talks in London on Wednesday.

To be absolutely clear, this is not solely a bargaining point. There is a substantive legal and parliamentary dimension to the Scottish contribution to this complex constitutional debate.

But there is some old-fashioned political pressure too. Scotland may not be able to veto or thwart Brexit. But further obstacles or hurdles could be added.

- Published8 November 2016

- Published8 November 2016