Testing times for Scottish education

- Published

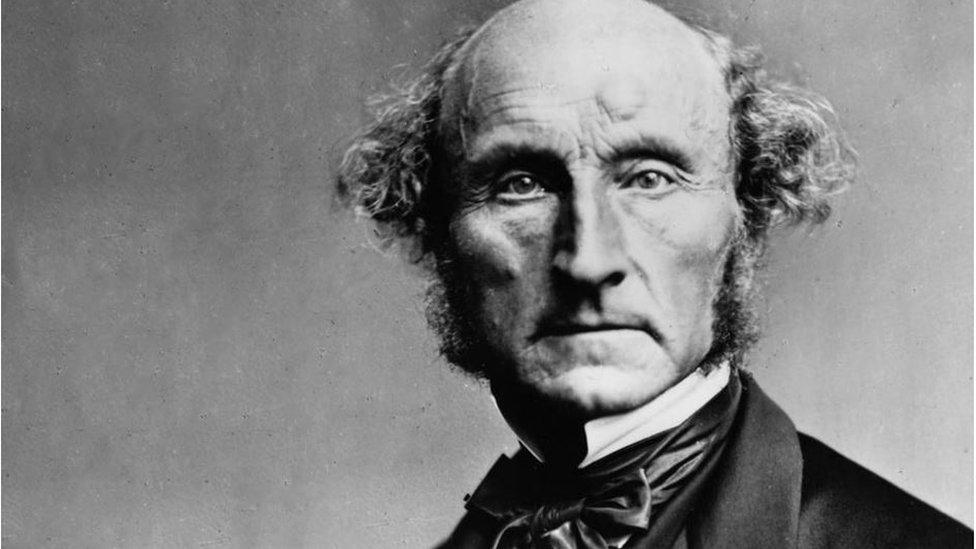

John Stuart Mill was taught by his stern scholastic father

The early years of John Stuart Mill, it would seem, were scarcely devoted to the pursuit of pleasure.

Not for him interactive computer games involving gruesomely athletic dwarves - or even their 19th Century equivalent, tales of fantasy and folklore most famously gathered, as John grew up, by the Brothers Grimm.

At the age of three, JSM studied Greek. It was Latin when he was eight. By the time he was 12, he was absorbed in the study of Logic.

Young John, it should be said, did not attend his local comprehensive. Or academy. Or grammar school. Or selective independent. Or boarding school.

No, the juvenile who later became the founder of Utilitarianism as a philosophical system - and served as Rector at St Andrews - was taught by his stern, scholastic Scottish father, James. John then assumed the task of teaching his siblings.

'Literally mediocre'

One can imagine what John Stuart Mill and, perhaps even more so, his old man would have made of the latest figures charting Scottish education against international comparators. The Pisa study.

For this OECD exercise, conducted last year, half a million 15-year-olds in a wide range of countries sat tests in numeracy, literacy and science. The latest figures show Scotland slipping back, now no better than average in any of the disciplines scrutinised.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, at least at Holyrood, that this is an appalling performance. Scottish education has fallen back to a situation where it is, literally, mediocre.

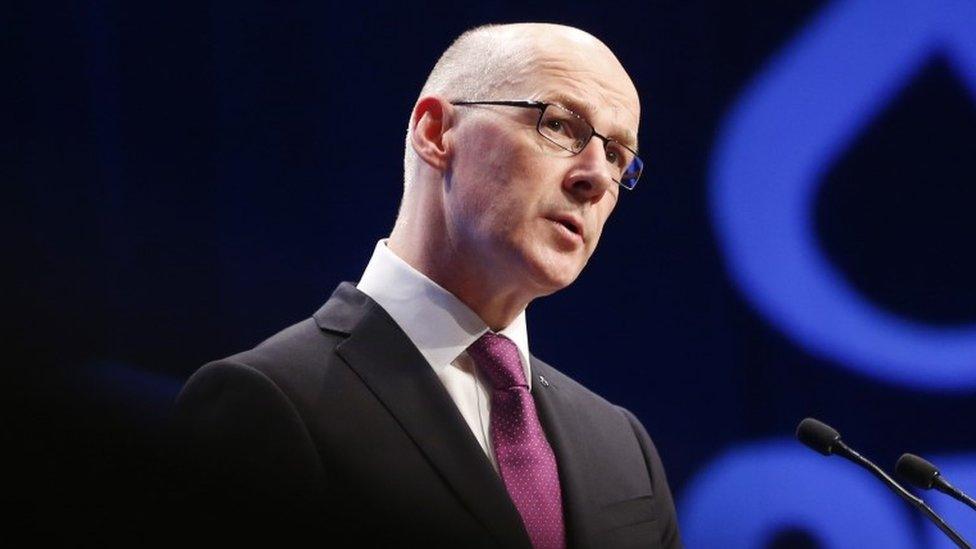

Education Secretary John Swinney called the results "uncomfortable"

At which point, opinion diverges.

Opposition parties, entirely understandably from their point of view, are inclined to blame the governing SNP. Indeed, they are rushing forward to do so.

It falls to John Swinney to respond. He is now education secretary and was, for many years prior to that, the man responsible for Scotland's budgetary allocation. His decisions funded schools.

Understandably, from his position, Mr Swinney says the "uncomfortable" results demonstrated the need for radical reform. Reform which, he argued, was already under way through the review of governance and other matters.

Curriculum control

At which point, Labour accuses Mr Swinney of using the results as a bogus conduit to pursue his "centralising" agenda. At which point, the education secretary says his plans are about empowering schools. At which point….

To be clear, this debate is entirely legitimate. As is the discussion about funding, about the provision of classroom support, about curriculum control, about in-school testing, about the nature of national exams.

All important. All relevant. All thoroughly familiar. A discourse which has persisted in various guises throughout the period of steady decline in Scotland's Pisainternational ranking - while education systems in Asia continue to top the table.

Education systems in Asia continue to top the table

To emphasise, I am not chiding the politicians for debate and argument. Indeed, such exchanges are essential. But perhaps we might begin with a few thoughts anent the essential nature of education - and the test which has provoked this fresh outbreak of controversy.

The Pisa test does not examine social or interpersonal skills. It does not look at the value of collaborative working. It tests excellence. Excellence - or otherwise - in core skills. Again, literacy, numeracy and science.

Should we not firstly ask ourselves: Do we favour excellence? Are we supportive of demonstrable academic ability?

Underlying philosophy

And, if we do, let us not wriggle out of the challenge by advocating "excellence for all". That is, to a large degree, meaningless, even oxymoronic.

It is, however, possible to envisage an education system which supports excellence - genuine excellence, academic rigour and discipline - while simultaneously seeking to give every single child the fullest possible opportunity to achieve to the best of their abilities.

That latter element, as I would read it, is the underlying philosophy of No Child Left Behind.

The Pisa test examines literacy, numeracy and science

It can be all too easy to be cynical about education. For example, the following has been said of Curriculum for Excellence. "It is not about excellence. It is not a curriculum. The only word which is true is 'for'".

However, the most significant conversation I recall with an educationalist was a chat with a head teacher from a school in one of the toughest schemes in Scotland.

She said that the biggest change she made was to chide pupils - and, even more so, teachers - to raise their expectations. She said that if we expect our children to fail then, guess what? They will fail.

If, to the contrary, we make clear that failure - that falling back - is not acceptable, even in a "struggling" school. Then guess what? Aspiration and ambition can produce relative success. I stress, relative.

But enough, if widely repeated, to help push Scotland back up that league table. If, to underline, that is what we genuinely want.

There is no need to replicate the pedagogy inflicted upon J.S. Mill. That would be unlikely to result in the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

But we might perhaps contemplate young John's early academic gifts and conclude that we are entitled to expect more from our system of education.

- Published6 December 2016