Is Scotland stepping closer to a second independence referendum?

- Published

Prime Minister Theresa May made clear this week the UK is to leave the EU's single market. Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had wanted the UK to stay in. So, does that mean we are closer to having a second Scottish independence referendum? Here I weigh up the issues.

Indyref2 could potentially leave Scots choosing between the EU and the UK

In the immediate aftermath of the EU referendum result, Nicola Sturgeon said "indyref2" was "highly likely".

After Theresa May set out some of her Brexit plans, indyref2 became even "more likely"; indeed, when the first minister was asked by BBC Scotland whether a vote was "all but inevitable", she said that was "very likely the case".

And yet, the first minister has not yet fired the starting gun. As strongly as she has spoken on the matter, her language remains hypothetical.

Launching her "Scotland's Place in Europe, external" paper of Brexit proposals, Ms Sturgeon laid out three options.

The UK as a whole remain in the European single market

That a differentiated deal be struck to keep Scotland alone in said market

Scotland reconsiders the issue of independence

Theresa May has scotched number one, comprehensively. And for all her talk of protecting the "precious union" of the UK, number two seems to be a diminishing prospect. So are we moving on to number three?

Here are seven issues Nicola Sturgeon will need to look at before she goes back to the polls.

1. Brexit and uncertainty

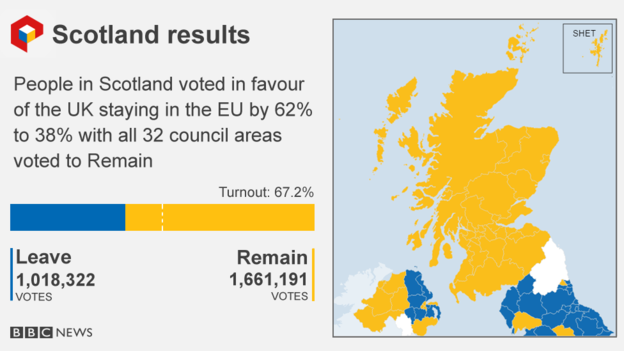

Every council area in Scotland voted Remain in the EU referendum

Brexit is the driving force in politics across the UK right now; and it is the source of the division which might bring an independence referendum to pass.

In case you hadn't heard, the majority of Scottish voters backed Remain, while the UK as a whole backed Leave.

Beyond that, Nicola Sturgeon and Theresa May take completely different approaches when it comes to Brexit.

The first minister comes at the issue like a jigsaw puzzle; she looks for recognised pieces like EFTA, the customs union and free movement which can be slotted together in a logical fashion to look like the picture on the box - of Scotland in Europe. Her options paper roots out precedent for every element, every piece of the puzzle, drawing comparisons from the Faroe Islands to Svalbard.

The prime minister meanwhile sees Brexit more like a painting. It's a creative act, conjuring up something new and unique. Never mind the Norway model, she demands her own "bespoke" deal, like nothing Europe has ever seen before.

The trouble is, we don't really know what the painting is going to look like. We have half an idea what Mrs May is trying to sketch out, but there are 27 other countries frantically swabbing at the canvas too (OK, that metaphor has probably been tortured enough).

So an indyref before the Brexit negotiations are complete would end up being a choice between two hypotheticals; two uncertain futures.

Can Ms Sturgeon persuade voters that the uncertainty of life outside the UK would be preferable to the uncertainty of life outside the EU?

2. Legality

Could Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon come to an agreement over a referendum?

Can Nicola Sturgeon even call a referendum?

Getting a referendum bill through Holyrood would not be an issue. The SNP may be a minority government, but the votes of the Greens would get it over the line comfortably.

But could Westminster prove more of a stumbling block?

The power to call a referendum remains a reserved matter; the 2014 vote was held after an agreement between Alex Salmond and David Cameron. Would Theresa May go down a similar route?

It's fair to say the prime minister has one or two other things on her plate at the moment, but she has made the "preservation of our precious union" one of her bigger priorities - it was number three in a list of 12 in her Brexit plans speech.

Politically, it could be difficult for her to actually refuse permission - that would probably only boost anti-Westminster sentiment. And she will be aware that a Yes vote even in an unauthorised vote could potentially be fatally destabilising.

3. Timing

When might Ms Sturgeon take Scotland back to the polls?

If Ms Sturgeon is going to fire the starting gun, when would she aim to do it?

This year seems to be off the table already; even with a consultation in the books, from a basic legislative standpoint it would be a struggle to have everything ready for a snap poll in 2017. There are also council elections to focus on this May.

The Scottish Greens have been agitating for a referendum halfway through the Brexit process, to settle the issue before Scotland is taken out of the EU along with the rest of the UK.

Former FM Alex Salmond, a man who knows a thing or two about calling referendums, has also suggested autumn 2018 as a suitable date.

However, other leading nationalists have been more cautious - Alex Neil, for once, has warned against being "stampeded", external into a "premature and unnecessarily risky" referendum.

Exactly when Ms Sturgeon might take the plunge may well depend on how the Brexit process unfolds - again, a matter of some uncertainty.

In any case, as Campbell Gunn, a former adviser to both Mr Salmond and Ms Sturgeon, noted this week, external - the first minister is "a canny politician" who "won't be railroaded into a vote she isn't sure of winning".

4. Europe

Ms Sturgeon - pictured in Brussels with European Parliament President Martin Schulz - wants Scotland to stay in the EU

What to do about Europe? Ms Sturgeon has said her ideal solution would be an independent Scotland being a member state of the EU.

How would this work? Many of the timetables mooted above aim specifically to win independence before Brexit is complete, in effect to try to keep Scotland in as the rest of the UK leaves.

But even on a very fast secession timetable, the UK would have left the EU long before Scotland made it out the door. So if Scotland was allowed to effectively 'inherit' the UK's place in the EU - a matter of some dispute in itself - the transition period would be extremely complicated.

In any case, over time the SNP's rhetoric has changed somewhat since the Brexit vote. Immediately after the referendum, the talk was of protecting Scotland's place in the EU. This softened to single market membership, and later to "access to" said market - but has now swung back a step.

In December, Mike Russell told the Scottish Affairs Committee that membership "is not possible" without being a full member of the EU. He said this was why there was "a range of other language", adding: "We've used 'involvement in' more than anything else".

However, the 'Scotland's Place in Europe' paper, published 13 days after Mr Russell's comments, is specific in seeking "single market membership".

Ms Sturgeon has been clear that the paper is a "compromise" position; so we can probably presume that removing the need to compromise would see her push for full EU membership. How popular that would be with the hundreds of thousands of SNP supporters who voted Leave remains to be seen.

5. The electorate

Would a new Yes campaign be able to build support in the way it did in 2014?

The million-dollar question, on which all of this hinges. Could Ms Sturgeon win indyref2?

Polls showed a "Brexit bounce" in support for independence after the EU referendum - but it was short-lived, petering out by the end of June. More or less every poll since has shown backing largely unchanged from 2014.

In any case, can we trust what polls say? Pollsters have had a fairly torrid time in recent years, with the electorate seemingly a more and more unpredictable beast.

The SNP has been doing its own research, via a "national conversation", and is said to have gathered two million responses - although it remains unclear how many people actually filled it in, and or what they said.

As polarised as Scottish political debate has become since 2014, this is still a complicated picture. There's the Yes vs No divide, but also Remain vs Leave, on top of party loyalties.

A million people voted Leave, after all. Would many of them sign up to independence if it comes bundled with the EU membership they rejected last June? Equally, could Remain voters be persuaded back secession en masse?

Turnout could also be an issue. It was massive in 2014, at 84.59%, but has been on the slide in most ensuing votes - it was down to 55.6% for the Holyrood election last May, and is likely to shrink still further in this year's council poll. Could turnout hit such heights a second time around? If not, how would that affect the result?

6. Economics

Would an independent Scotland end up using the pound or the Euro? Or something else?

One of the core issues of the last referendum was the economy; some would say it was where the Yes case fell down.

Alex Bell, a one-time advisor to Alex Salmond, has said the 2014 case for independence is now "dead", while the man himself has said the Yes side were "gazumped" on currency.

Need more? Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, a member of both Mr Salmond and Ms Sturgeon's economic advisory teams, has conceded that the proposal to share the pound with the UK "may have been a mistake".

So there's appetite for change on the economic case within the Yes camp.

Ms Sturgeon has previously insisted that "the pound is Scotland's currency" - albeit before it plummeted post-EUref - but her deputy Angus Robertson and various other SNP figures have suggested looking at a "Scottish pound".

Equally, might the EU demand Scotland adopt the Euro as part of a route back into membership - and an implicit dig at Brexiteer Britain?

Elsewhere, the Common Weal think-tank has put together an entire White Paper project, external - very much a work in progress, but also including proposals for a new currency - proposals enthusiastically backed at the latest meeting of the Scottish Independence Convention.

Common Weal reckon setting up a new Scottish state would carry a one-off cost of £18.8bn, and say it would run a £8.8bn deficit in its first year of independence.

Now these are, by their own admission, "very rough" estimates. But they are the kind of costed proposals Ms Sturgeon has the likes of Andrew Wilson beavering away on, to build a new economic case for independence.

As an aside, does economics matter as much in the era of Brexit? After all, questions of sovereignty won out over dire economic warnings in the EU referendum. In any case, Ms Sturgeon will not pull the trigger on indyref2 without firm economic plans in hand.

7. Border and markets

An independent Scotland would seek to avoid border controls with the rest of the UK

Much of the Holyrood debate around independence over Brexit has been characterised by opposition parties, chiefly Labour and the Tories, pointing out that Scotland does a lot more direct trade with the UK than it does with the EU.

Now, obviously the UK market wouldn't simply disappear if Scotland were independent - in the same way that the European market isn't going to be sealed off to a post-Brexit Britain. However, relationships would undoubtedly change.

The scale of that change would be the subject of intense debate in an indyref2 campaign, with the opposing sides doubtless coming up with radically different yet equally improvable estimates.

The attitude of businesses would play a key role in the campaign; would they want to stay in Scotland and the EU, or head to Theresa May's "global Britain"? Again, how the Brexit process pans out might be instructive on that front.

And what of borders? Ms Sturgeon's Brexit plan includes Scotland staying part of the UK and Ireland's common travel area, so it seems likely she would seek a similar deal even as an independent state.

This was a simpler matter in 2014, before EU membership was bundled into the mix, but Yessers could point to the pledge there will not be a hard border in Northern Ireland for precedent.

Depending on how Brexit pans out (as usual), Ireland may also provide an example of how a customs border would work between and independent Scotland and the UK - and indeed Ms Sturgeon has also already tried to set out proposals for avoiding this in her argument for Scots single market membership.

- Published18 January 2017

- Published17 January 2017

- Published17 January 2017